But, had it been the beginning of some great labour with the same end in view—had it been the commencement of a long journey, to be performed on foot in that inclement season of the year, to be pursued under very privation and difficulty, and to be achieved only with great distress, fatigue, and suffering—had it been the dawn of some painful enterprise, certain to task his utmost powers of resolution and endurance, and to need his utmost fortitude, but only likely to end, if happily achieved, in good fortune and delight to Nell—Kit’s cheerful zeal would have been as highly roused: Kit’s ardour and impatience would have been, at least, the same.

Nor was he alone excited and eager. Before he had been up a quarter of an hour the whole house were astir and busy. Everybody hurried to do something towards facilitating the preparations. The single gentleman, it is true, could do nothing himself, but he overlooked everybody else and was more locomotive than anybody. The work of packing and making ready went briskly on, and by daybreak every preparation for the journey was completed. Then Kit began to wish they had not been quite so nimble; for the travelling-carriage which had been hired for the occasion was not to arrive until nine o’clock, and there was nothing but breakfast to fill up the intervening blank of one hour and a half. Yes there was, though. There was Barbara. Barbara was busy, to be sure, but so much the better—Kit could help her, and that would pass away the time better than any means that could be devised. Barbara had no objection to this arrangement, and Kit, tracking out the idea which had come upon him so suddenly overnight, began to think that surely Barbara was fond of him, and surely he was fond of Barbara.

Now, Barbara, if the truth must be told—as it must and ought to be—Barbara seemed, of all the little household, to take least pleasure in the bustle of the occasion; and when Kit, in the openness of his heart, told her how glad and overjoyed it made him, Barbara became more downcast still, and seemed to have even less pleasure in it than before!

‘You have not been home so long, Christopher,’ said Barbara—and it is impossible to tell how carelessly she said it—‘You have not been home so long, that you need to be glad to go away again, I should think.’

‘But for such a purpose,’ returned Kit. ‘To bring back Miss Nell! To see her again! Only think of that! I am so pleased too, to think that you will see her, Barbara, at last.’

Barbara did not absolutely say that she felt no gratification on this point, but she expressed the sentiment so plainly by one little toss of her head, that Kit was quite disconcerted, and wondered, in his simplicity, why she was so cool about it.

‘You’ll say she has the sweetest and beautifullest face you ever saw, I know,’ said Kit, rubbing his hands. ‘I’m sure you’ll say that.’

Barbara tossed her head again.

‘What’s the matter, Barbara?’ said Kit.

‘Nothing,’ cried Barbara. And Barbara pouted—not sulkily, or in an ugly manner, but just enough to make her look more cherry-lipped than ever.

There is no school in which a pupil gets on so fast, as that in which Kit became a scholar when he gave Barbara the kiss. He saw what Barbara meant now—he had his lesson by heart all at once—she was the book—there it was before him, as plain as print.

‘Barbara,’ said Kit, ‘you’re not cross with me?’

Oh dear no! Why should Barbara be cross? And what right had she to be cross? And what did it matter whether she was cross or not? Who minded her!

‘Why, I do,’ said Kit. ‘Of course I do.’

Barbara didn’t see why it was of course, at all.

Kit was sure she must. Would she think again?

Certainly, Barbara would think again. No, she didn’t see why it was of course. She didn’t understand what Christopher meant. And besides she was sure they wanted her up stairs by this time, and she must go, indeed—

‘No, but Barbara,’ said Kit, detaining her gently, ‘let us part friends. I was always thinking of you, in my troubles. I should have been a great deal more miserable than I was, if it hadn’t been for you.’

Goodness gracious, how pretty Barbara was when she coloured—and when she trembled, like a little shrinking bird!

‘I am telling you the truth, Barbara, upon my word, but not half so strong as I could wish,’ said Kit. ‘When I want you to be pleased to see Miss Nell, it’s only because I like you to be pleased with what pleases me—that’s all. As to her, Barbara, I think I could almost die to do her service, but you would think so too, if you knew her as I do. I am sure you would.’

Barbara was touched, and sorry to have appeared indifferent.

‘I have been used, you see,’ said Kit, ‘to talk and think of her, almost as if she was an angel. When I look forward to meeting her again, I think of her smiling as she used to do, and being glad to see me, and putting out her hand and saying, “It’s my own old Kit,” or some such words as those—like what she used to say. I think of seeing her happy, and with friends about her, and brought up as she deserves, and as she ought to be. When I think of myself, it’s as her old servant, and one that loved her dearly, as his kind, good, gentle mistress; and who would have gone—yes, and still would go—through any harm to serve her. Once, I couldn’t help being afraid that if she came back with friends about her she might forget, or be ashamed of having known, a humble lad like me, and so might speak coldly, which would have cut me, Barbara, deeper than I can tell. But when I came to think again, I felt sure that I was doing her wrong in this; and so I went on, as I did at first, hoping to see her once more, just as she used to be. Hoping this, and remembering what she was, has made me feel as if I would always try to please her, and always be what I should like to seem to her if I was still her servant. If I’m the better for that—and I don’t think I’m the worse—I am grateful to her for it, and love and honour her the more. That’s the plain honest truth, dear Barbara, upon my word it is!’

Little Barbara was not of a wayward or capricious nature, and, being full of remorse, melted into tears. To what more conversation this might have led, we need not stop to inquire; for the wheels of the carriage were heard at that moment, and, being followed by a smart ring at the garden gate, caused the bustle in the house, which had laid dormant for a short time, to burst again into tenfold life and vigour.

Simultaneously with the travelling equipage, arrived Mr Chuckster in a hackney cab, with certain papers and supplies of money for the single gentleman, into whose hands he delivered them. This duty discharged, he subsided into the bosom of the family; and, entertaining himself with a strolling or peripatetic breakfast, watched, with genteel indifference, the process of loading the carriage.

‘Snobby’s in this, I see, Sir?’ he said to Mr Abel Garland. ‘I thought he wasn’t in the last trip because it was expected that his presence wouldn’t be acceptable to the ancient buffalo.’

‘To whom, Sir?’ demanded Mr Abel.

‘To the old gentleman,’ returned Mr Chuckster, slightly abashed.

‘Our client prefers to take him now,’ said Mr Abel, drily. ‘There is no longer any need for that precaution, as my father’s relationship to a gentleman in whom the objects of his search have full confidence, will be a sufficient guarantee for the friendly nature of their errand.’

‘Ah!’ thought Mr Chuckster, looking out of window, ‘anybody but me! Snobby before me, of course. He didn’t happen to take that particular five-pound note, but I have not the smallest doubt that he’s always up to something of that sort. I always said it, long before this came out. Devilish pretty girl that! ‘Pon my soul, an amazing little creature!’

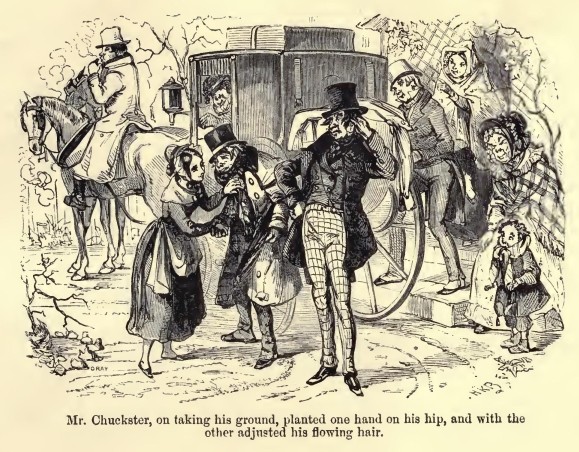

Barbara was the subject of Mr Chuckster’s commendations; and as she was lingering near the carriage (all being now ready for its departure), that gentleman was suddenly seized with a strong interest in the proceedings, which impelled him to swagger down the garden, and take up his position at a convenient ogling distance. Having had great experience of the sex, and being perfectly acquainted with all those little artifices which find the readiest road to their hearts, Mr Chuckster, on taking his ground, planted one hand on his hip, and with the other adjusted his flowing hair. This is a favourite attitude in the polite circles, and, accompanied with a graceful whistling, has been known to do immense execution.

Such, however, is the difference between town and country, that nobody took the smallest notice of this insinuating figure; the wretches being wholly engaged in bidding the travellers farewell, in kissing hands to each other, waving handkerchiefs, and the like tame and vulgar practices. For now the single gentleman and Mr Garland were in the carriage, and the post-boy was in the saddle, and Kit, well wrapped and muffled up, was in the rumble behind; and Mrs Garland was there, and Mr Abel was there, and Kit’s mother was there, and little Jacob was there, and Barbara’s mother was visible in remote perspective, nursing the ever-wakeful baby; and all were nodding, beckoning, curtseying, or crying out, ‘Good bye!’ with all the energy they could express. In another minute, the carriage was out of sight; and Mr Chuckster remained alone on the spot where it had lately been, with a vision of Kit standing up in the rumble waving his hand to Barbara, and of Barbara in the full light and lustre of his eyes—his eyes—Chuckster’s—Chuckster the successful—on whom ladies of quality had looked with favour from phaetons in the parks on Sundays—waving hers to Kit!

How Mr Chuckster, entranced by this monstrous fact, stood for some time rooted to the earth, protesting within himself that Kit was the Prince of felonious characters, and very Emperor or Great Mogul of Snobs, and how he clearly traced this revolting circumstance back to that old villany of the shilling, are matters foreign to our purpose; which is to track the rolling wheels, and bear the travellers company on their cold, bleak journey.

It was a bitter day. A keen wind was blowing, and rushed against them fiercely: bleaching the hard ground, shaking the white frost from the trees and hedges, and whirling it away like dust. But little cared Kit for weather. There was a freedom and freshness in the wind, as it came howling by, which, let it cut never so sharp, was welcome. As it swept on with its cloud of frost, bearing down the dry twigs and boughs and withered leaves, and carrying them away pell-mell, it seemed as though some general sympathy had got abroad, and everything was in a hurry, like themselves. The harder the gusts, the better progress they appeared to make. It was a good thing to go struggling and fighting forward, vanquishing them one by one; to watch them driving up, gathering strength and fury as they came along; to bend for a moment, as they whistled past; and then to look back and see them speed away, their hoarse noise dying in the distance, and the stout trees cowering down before them.

All day long, it blew without cessation. The night was clear and starlit, but the wind had not fallen, and the cold was piercing. Sometimes—towards the end of a long stage—Kit could not help wishing it were a little warmer: but when they stopped to change horses, and he had had a good run, and what with that, and the bustle of paying the old postilion, and rousing the new one, and running to and fro again until the horses were put to, he was so warm that the blood tingled and smarted in his fingers’ ends—then, he felt as if to have it one degree less cold would be to lose half the delight and glory of the journey: and up he jumped again, right cheerily, singing to the merry music of the wheels as they rolled away, and, leaving the townspeople in their warm beds, pursued their course along the lonely road.

Meantime the two gentlemen inside, who were little disposed to sleep, beguiled the time with conversation. As both were anxious and expectant, it naturally turned upon the subject of their expedition, on the manner in which it had been brought about, and on the hopes and fears they entertained respecting it. Of the former they had many, of the latter few—none perhaps beyond that indefinable uneasiness which is inseparable from suddenly awakened hope, and protracted expectation.

In one of the pauses of their discourse, and when half the night had worn away, the single gentleman, who had gradually become more and more silent and thoughtful, turned to his companion and said abruptly:

‘Are you a good listener?’

‘Like most other men, I suppose,’ returned Mr Garland, smiling. ‘I can be, if I am interested; and if not interested, I should still try to appear so. Why do you ask?’

‘I have a short narrative on my lips,’ rejoined his friend, ‘and will try you with it. It is very brief.’

Pausing for no reply, he laid his hand on the old gentleman’s sleeve, and proceeded thus:

‘There were once two brothers, who loved each other dearly. There was a disparity in their ages—some twelve years. I am not sure but they may insensibly have loved each other the better for that reason. Wide as the interval between them was, however, they became rivals too soon. The deepest and strongest affection of both their hearts settled upon one object.

‘The youngest—there were reasons for his being sensitive and watchful—was the first to find this out. I will not tell you what misery he underwent, what agony of soul he knew, how great his mental struggle was. He had been a sickly child. His brother, patient and considerate in the midst of his own high health and strength, had many and many a day denied himself the sports he loved, to sit beside his couch, telling him old stories till his pale face lighted up with an unwonted glow; to carry him in his arms to some green spot, where he could tend the poor pensive boy as he looked upon the bright summer day, and saw all nature healthy but himself; to be, in any way, his fond and faithful nurse. I may not dwell on all he did, to make the poor, weak creature love him, or my tale would have no end. But when the time of trial came, the younger brother’s heart was full of those old days. Heaven strengthened it to repay the sacrifices of inconsiderate youth by one of thoughtful manhood. He left his brother to be happy. The truth never passed his lips, and he quitted the country, hoping to die abroad.

‘The elder brother married her. She was in Heaven before long, and left him with an infant daughter.

‘If you have seen the picture-gallery of any one old family, you will remember how the same face and figure—often the fairest and slightest of them all—come upon you in different generations; and how you trace the same sweet girl through a long line of portraits—never growing old or changing—the Good Angel of the race—abiding by them in all reverses—redeeming all their sins—

‘In this daughter the mother lived again. You may judge with what devotion he who lost that mother almost in the winning, clung to this girl, her breathing image. She grew to womanhood, and gave her heart to one who could not know its worth. Well! Her fond father could not see her pine and droop. He might be more deserving than he thought him. He surely might become so, with a wife like her. He joined their hands, and they were married.

‘Through all the misery that followed this union; through all the cold neglect and undeserved reproach; through all the poverty he brought upon her; through all the struggles of their daily life, too mean and pitiful to tell, but dreadful to endure; she toiled on, in the deep devotion of her spirit, and in her better nature, as only women can. Her means and substance wasted; her father nearly beggared by her husband’s hand, and the hourly witness (for they lived now under one roof) of her ill-usage and unhappiness,—she never, but for him, bewailed her fate. Patient, and upheld by strong affection to the last, she died a widow of some three weeks’ date, leaving to her father’s care two orphans; one a son of ten or twelve years old; the other a girl—such another infant child—the same in helplessness, in age, in form, in feature—as she had been herself when her young mother died.

‘The elder brother, grandfather to these two children, was now a broken man; crushed and borne down, less by the weight of years than by the heavy hand of sorrow. With the wreck of his possessions, he began to trade—in pictures first, and then in curious ancient things. He had entertained a fondness for such matters from a boy, and the tastes he had cultivated were now to yield him an anxious and precarious subsistence.

‘The boy grew like his father in mind and person; the girl so like her mother, that when the old man had her on his knee, and looked into her mild blue eyes, he felt as if awakening from a wretched dream, and his daughter were a little child again. The wayward boy soon spurned the shelter of his roof, and sought associates more congenial to his taste. The old man and the child dwelt alone together.

‘It was then, when the love of two dead people who had been nearest and dearest to his heart, was all transferred to this slight creature; when her face, constantly before him, reminded him, from hour to hour, of the too early change he had seen in such another—of all the sufferings he had watched and known, and all his child had undergone; when the young man’s profligate and hardened course drained him of money as his father’s had, and even sometimes occasioned them temporary privation and distress; it was then that there began to beset him, and to be ever in his mind, a gloomy dread of poverty and want. He had no thought for himself in this. His fear was for the child. It was a spectre in his house, and haunted him night and day.

‘The younger brother had been a traveller in many countries, and had made his pilgrimage through life alone. His voluntary banishment had been misconstrued, and he had borne (not without pain) reproach and slight for doing that which had wrung his heart, and cast a mournful shadow on his path. Apart from this, communication between him and the elder was difficult, and uncertain, and often failed; still, it was not so wholly broken off but that he learnt—with long blanks and gaps between each interval of information—all that I have told you now.

‘Then, dreams of their young, happy life—happy to him though laden with pain and early care—visited his pillow yet oftener than before; and every night, a boy again, he was at his brother’s side. With the utmost speed he could exert, he settled his affairs; converted into money all the goods he had; and, with honourable wealth enough for both, with open heart and hand, with limbs that trembled as they bore him on, with emotion such as men can hardly bear and live, arrived one evening at his brother’s door!’

The narrator, whose voice had faltered lately, stopped.

‘The rest,’ said Mr Garland, pressing his hand after a pause, ‘I know.’

‘Yes,’ rejoined his friend, ‘we may spare ourselves the sequel. You know the poor result of all my search. Even when by dint of such inquiries as the utmost vigilance and sagacity could set on foot, we found they had been seen with two poor travelling showmen—and in time discovered the men themselves—and in time, the actual place of their retreat; even then, we were too late. Pray God, we are not too late again!’

‘We cannot be,’ said Mr Garland. ‘This time we must succeed.’

‘I have believed and hoped so,’ returned the other. ‘I try to believe and hope so still. But a heavy weight has fallen on my spirits, my good friend, and the sadness that gathers over me, will yield to neither hope nor reason.’

‘That does not surprise me,’ said Mr Garland; ‘it is a natural consequence of the events you have recalled; of this dreary time and place; and above all, of this wild and dismal night. A dismal night, indeed! Hark! how the wind is howling!’