The intrepid aeronauts alight before a small dark house, once the residence of Mr Sampson Brass.

In the parlour window of this little habitation, which is so close upon the footway that the passenger who takes the wall brushes the dim glass with his coat sleeve—much to its improvement, for it is very dirty—in this parlour window in the days of its occupation by Sampson Brass, there hung, all awry and slack, and discoloured by the sun, a curtain of faded green, so threadbare from long service as by no means to intercept the view of the little dark room, but rather to afford a favourable medium through which to observe it accurately. There was not much to look at. A rickety table, with spare bundles of papers, yellow and ragged from long carriage in the pocket, ostentatiously displayed upon its top; a couple of stools set face to face on opposite sides of this crazy piece of furniture; a treacherous old chair by the fire-place, whose withered arms had hugged full many a client and helped to squeeze him dry; a second-hand wig box, used as a depository for blank writs and declarations and other small forms of law, once the sole contents of the head which belonged to the wig which belonged to the box, as they were now of the box itself; two or three common books of practice; a jar of ink, a pounce box, a stunted hearth-broom, a carpet trodden to shreds but still clinging with the tightness of desperation to its tacks—these, with the yellow wainscot of the walls, the smoke-discoloured ceiling, the dust and cobwebs, were among the most prominent decorations of the office of Mr Sampson Brass.

But this was mere still-life, of no greater importance than the plate, ‘Brass, Solicitor,’ upon the door, and the bill, ‘First floor to let to a single gentleman,’ which was tied to the knocker. The office commonly held two examples of animated nature, more to the purpose of this history, and in whom it has a stronger interest and more particular concern.

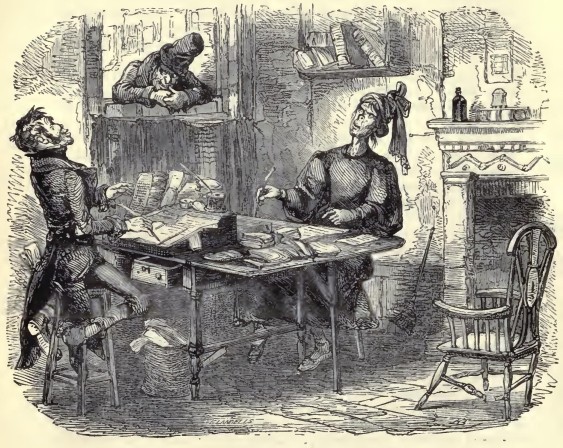

Of these, one was Mr Brass himself, who has already appeared in these pages. The other was his clerk, assistant, housekeeper, secretary, confidential plotter, adviser, intriguer, and bill of cost increaser, Miss Brass—a kind of amazon at common law, of whom it may be desirable to offer a brief description.

Miss Sally Brass, then, was a lady of thirty-five or thereabouts, of a gaunt and bony figure, and a resolute bearing, which if it repressed the softer emotions of love, and kept admirers at a distance, certainly inspired a feeling akin to awe in the breasts of those male strangers who had the happiness to approach her. In face she bore a striking resemblance to her brother, Sampson—so exact, indeed, was the likeness between them, that had it consorted with Miss Brass’s maiden modesty and gentle womanhood to have assumed her brother’s clothes in a frolic and sat down beside him, it would have been difficult for the oldest friend of the family to determine which was Sampson and which Sally, especially as the lady carried upon her upper lip certain reddish demonstrations, which, if the imagination had been assisted by her attire, might have been mistaken for a beard. These were, however, in all probability, nothing more than eyelashes in a wrong place, as the eyes of Miss Brass were quite free from any such natural impertinencies. In complexion Miss Brass was sallow—rather a dirty sallow, so to speak—but this hue was agreeably relieved by the healthy glow which mantled in the extreme tip of her laughing nose. Her voice was exceedingly impressive—deep and rich in quality, and, once heard, not easily forgotten. Her usual dress was a green gown, in colour not unlike the curtain of the office window, made tight to the figure, and terminating at the throat, where it was fastened behind by a peculiarly large and massive button. Feeling, no doubt, that simplicity and plainness are the soul of elegance, Miss Brass wore no collar or kerchief except upon her head, which was invariably ornamented with a brown gauze scarf, like the wing of the fabled vampire, and which, twisted into any form that happened to suggest itself, formed an easy and graceful head-dress.

Such was Miss Brass in person. In mind, she was of a strong and vigorous turn, having from her earliest youth devoted herself with uncommon ardour to the study of law; not wasting her speculations upon its eagle flights, which are rare, but tracing it attentively through all the slippery and eel-like crawlings in which it commonly pursues its way. Nor had she, like many persons of great intellect, confined herself to theory, or stopped short where practical usefulness begins; inasmuch as she could ingross, fair-copy, fill up printed forms with perfect accuracy, and, in short, transact any ordinary duty of the office down to pouncing a skin of parchment or mending a pen. It is difficult to understand how, possessed of these combined attractions, she should remain Miss Brass; but whether she had steeled her heart against mankind, or whether those who might have wooed and won her, were deterred by fears that, being learned in the law, she might have too near her fingers’ ends those particular statutes which regulate what are familiarly termed actions for breach, certain it is that she was still in a state of celibacy, and still in daily occupation of her old stool opposite to that of her brother Sampson. And equally certain it is, by the way, that between these two stools a great many people had come to the ground.

One morning Mr Sampson Brass sat upon his stool copying some legal process, and viciously digging his pen deep into the paper, as if he were writing upon the very heart of the party against whom it was directed; and Miss Sally Brass sat upon her stool making a new pen preparatory to drawing out a little bill, which was her favourite occupation; and so they sat in silence for a long time, until Miss Brass broke silence.

‘Have you nearly done, Sammy?’ said Miss Brass; for in her mild and feminine lips, Sampson became Sammy, and all things were softened down.

‘No,’ returned her brother. ‘It would have been all done though, if you had helped at the right time.’

‘Oh yes, indeed,’ cried Miss Sally; ‘you want my help, don’t you?—you, too, that are going to keep a clerk!’

‘Am I going to keep a clerk for my own pleasure, or because of my own wish, you provoking rascal!’ said Mr Brass, putting his pen in his mouth, and grinning spitefully at his sister. ‘What do you taunt me about going to keep a clerk for?’

It may be observed in this place, lest the fact of Mr Brass calling a lady a rascal, should occasion any wonderment or surprise, that he was so habituated to having her near him in a man’s capacity, that he had gradually accustomed himself to talk to her as though she were really a man. And this feeling was so perfectly reciprocal, that not only did Mr Brass often call Miss Brass a rascal, or even put an adjective before the rascal, but Miss Brass looked upon it as quite a matter of course, and was as little moved as any other lady would be by being called an angel.

‘What do you taunt me, after three hours’ talk last night, with going to keep a clerk for?’ repeated Mr Brass, grinning again with the pen in his mouth, like some nobleman’s or gentleman’s crest. ‘Is it my fault?’

‘All I know is,’ said Miss Sally, smiling drily, for she delighted in nothing so much as irritating her brother, ‘that if every one of your clients is to force us to keep a clerk, whether we want to or not, you had better leave off business, strike yourself off the roll, and get taken in execution, as soon as you can.’

‘Have we got any other client like him?’ said Brass. ‘Have we got another client like him now—will you answer me that?’

‘Do you mean in the face!’ said his sister.

‘Do I mean in the face!’ sneered Sampson Brass, reaching over to take up the bill-book, and fluttering its leaves rapidly. ‘Look here—Daniel Quilp, Esquire—Daniel Quilp, Esquire—Daniel Quilp, Esquire—all through. Whether should I take a clerk that he recommends, and says, “this is the man for you,” or lose all this, eh?’

Miss Sally deigned to make no reply, but smiled again, and went on with her work.

‘But I know what it is,’ resumed Brass after a short silence. ‘You’re afraid you won’t have as long a finger in the business as you’ve been used to have. Do you think I don’t see through that?’

‘The business wouldn’t go on very long, I expect, without me,’ returned his sister composedly. ‘Don’t you be a fool and provoke me, Sammy, but mind what you’re doing, and do it.’

Sampson Brass, who was at heart in great fear of his sister, sulkily bent over his writing again, and listened as she said:

‘If I determined that the clerk ought not to come, of course he wouldn’t be allowed to come. You know that well enough, so don’t talk nonsense.’

Mr Brass received this observation with increased meekness, merely remarking, under his breath, that he didn’t like that kind of joking, and that Miss Sally would be ‘a much better fellow’ if she forbore to aggravate him. To this compliment Miss Sally replied, that she had a relish for the amusement, and had no intention to forego its gratification. Mr Brass not caring, as it seemed, to pursue the subject any further, they both plied their pens at a great pace, and there the discussion ended.

While they were thus employed, the window was suddenly darkened, as by some person standing close against it. As Mr Brass and Miss Sally looked up to ascertain the cause, the top sash was nimbly lowered from without, and Quilp thrust in his head.

‘Hallo!’ he said, standing on tip-toe on the window-sill, and looking down into the room. ‘Is there anybody at home? Is there any of the Devil’s ware here? Is Brass at a premium, eh?’

‘Ha, ha, ha!’ laughed the lawyer in an affected ecstasy. ‘Oh, very good, Sir! Oh, very good indeed! Quite eccentric! Dear me, what humour he has!’

‘Is that my Sally?’ croaked the dwarf, ogling the fair Miss Brass. ‘Is it Justice with the bandage off her eyes, and without the sword and scales? Is it the Strong Arm of the Law? Is it the Virgin of Bevis?’

‘What an amazing flow of spirits!’ cried Brass. ‘Upon my word, it’s quite extraordinary!’

‘Open the door,’ said Quilp, ‘I’ve got him here. Such a clerk for you, Brass, such a prize, such an ace of trumps. Be quick and open the door, or if there’s another lawyer near and he should happen to look out of window, he’ll snap him up before your eyes, he will.’

It is probable that the loss of the phoenix of clerks, even to a rival practitioner, would not have broken Mr Brass’s heart; but, pretending great alacrity, he rose from his seat, and going to the door, returned, introducing his client, who led by the hand no less a person than Mr Richard Swiveller.

‘There she is,’ said Quilp, stopping short at the door, and wrinkling up his eyebrows as he looked towards Miss Sally; ‘there is the woman I ought to have married—there is the beautiful Sarah—there is the female who has all the charms of her sex and none of their weaknesses. Oh Sally, Sally!’

To this amorous address Miss Brass briefly responded ‘Bother!’

‘Hard-hearted as the metal from which she takes her name,’ said Quilp. ‘Why don’t she change it—melt down the brass, and take another name?’

‘Hold your nonsense, Mr Quilp, do,’ returned Miss Sally, with a grim smile. ‘I wonder you’re not ashamed of yourself before a strange young man.’

‘The strange young man,’ said Quilp, handing Dick Swiveller forward, ‘is too susceptible himself not to understand me well. This is Mr Swiveller, my intimate friend—a gentleman of good family and great expectations, but who, having rather involved himself by youthful indiscretion, is content for a time to fill the humble station of a clerk—humble, but here most enviable. What a delicious atmosphere!’

If Mr Quilp spoke figuratively, and meant to imply that the air breathed by Miss Sally Brass was sweetened and rarefied by that dainty creature, he had doubtless good reason for what he said. But if he spoke of the delights of the atmosphere of Mr Brass’s office in a literal sense, he had certainly a peculiar taste, as it was of a close and earthy kind, and, besides being frequently impregnated with strong whiffs of the second-hand wearing apparel exposed for sale in Duke’s Place and Houndsditch, had a decided flavour of rats and mice, and a taint of mouldiness. Perhaps some doubts of its pure delight presented themselves to Mr Swiveller, as he gave vent to one or two short abrupt sniffs, and looked incredulously at the grinning dwarf.

‘Mr Swiveller,’ said Quilp, ‘being pretty well accustomed to the agricultural pursuits of sowing wild oats, Miss Sally, prudently considers that half a loaf is better than no bread. To be out of harm’s way he prudently thinks is something too, and therefore he accepts your brother’s offer. Brass, Mr Swiveller is yours.’

‘I am very glad, Sir,’ said Mr Brass, ‘very glad indeed. Mr Swiveller, Sir, is fortunate enough to have your friendship. You may be very proud, Sir, to have the friendship of Mr Quilp.’

Dick murmured something about never wanting a friend or a bottle to give him, and also gasped forth his favourite allusion to the wing of friendship and its never moulting a feather; but his faculties appeared to be absorbed in the contemplation of Miss Sally Brass, at whom he stared with blank and rueful looks, which delighted the watchful dwarf beyond measure. As to the divine Miss Sally herself, she rubbed her hands as men of business do, and took a few turns up and down the office with her pen behind her ear.

‘I suppose,’ said the dwarf, turning briskly to his legal friend, ‘that Mr Swiveller enters upon his duties at once? It’s Monday morning.’

‘At once, if you please, Sir, by all means,’ returned Brass.

‘Miss Sally will teach him law, the delightful study of the law,’ said Quilp; ‘she’ll be his guide, his friend, his companion, his Blackstone, his Coke upon Littleton, his Young Lawyer’s Best Companion.’

‘He is exceedingly eloquent,’ said Brass, like a man abstracted, and looking at the roofs of the opposite houses, with his hands in his pockets; ‘he has an extraordinary flow of language. Beautiful, really.’

‘With Miss Sally,’ Quilp went on, ‘and the beautiful fictions of the law, his days will pass like minutes. Those charming creations of the poet, John Doe and Richard Roe, when they first dawn upon him, will open a new world for the enlargement of his mind and the improvement of his heart.’

‘Oh, beautiful, beautiful! Beau-ti-ful indeed!’ cried Brass. ‘It’s a treat to hear him!’

‘Where will Mr Swiveller sit?’ said Quilp, looking round.

‘Why, we’ll buy another stool, sir,’ returned Brass. ‘We hadn’t any thoughts of having a gentleman with us, sir, until you were kind enough to suggest it, and our accommodation’s not extensive. We’ll look about for a second-hand stool, sir. In the meantime, if Mr Swiveller will take my seat, and try his hand at a fair copy of this ejectment, as I shall be out pretty well all the morning—’

‘Walk with me,’ said Quilp. ‘I have a word or two to say to you on points of business. Can you spare the time?’

‘Can I spare the time to walk with you, sir? You’re joking, sir, you’re joking with me,’ replied the lawyer, putting on his hat. ‘I’m ready, sir, quite ready. My time must be fully occupied indeed, sir, not to leave me time to walk with you. It’s not everybody, sir, who has an opportunity of improving himself by the conversation of Mr Quilp.’

The dwarf glanced sarcastically at his brazen friend, and, with a short dry cough, turned upon his heel to bid adieu to Miss Sally. After a very gallant parting on his side, and a very cool and gentlemanly sort of one on hers, he nodded to Dick Swiveller, and withdrew with the attorney.

Dick stood at the desk in a state of utter stupefaction, staring with all his might at the beauteous Sally, as if she had been some curious animal whose like had never lived. When the dwarf got into the street, he mounted again upon the window-sill, and looked into the office for a moment with a grinning face, as a man might peep into a cage. Dick glanced upward at him, but without any token of recognition; and long after he had disappeared, still stood gazing upon Miss Sally Brass, seeing or thinking of nothing else, and rooted to the spot.

Miss Brass being by this time deep in the bill of costs, took no notice whatever of Dick, but went scratching on, with a noisy pen, scoring down the figures with evident delight, and working like a steam-engine. There stood Dick, gazing now at the green gown, now at the brown head-dress, now at the face, and now at the rapid pen, in a state of stupid perplexity, wondering how he got into the company of that strange monster, and whether it was a dream and he would ever wake. At last he heaved a deep sigh, and began slowly pulling off his coat.

Mr Swiveller pulled off his coat, and folded it up with great elaboration, staring at Miss Sally all the time; then put on a blue jacket with a double row of gilt buttons, which he had originally ordered for aquatic expeditions, but had brought with him that morning for office purposes; and, still keeping his eye upon her, suffered himself to drop down silently upon Mr Brass’s stool. Then he underwent a relapse, and becoming powerless again, rested his chin upon his hand, and opened his eyes so wide, that it appeared quite out of the question that he could ever close them any more.

When he had looked so long that he could see nothing, Dick took his eyes off the fair object of his amazement, turned over the leaves of the draft he was to copy, dipped his pen into the inkstand, and at last, and by slow approaches, began to write. But he had not written half-a-dozen words when, reaching over to the inkstand to take a fresh dip, he happened to raise his eyes. There was the intolerable brown head-dress—there was the green gown—there, in short, was Miss Sally Brass, arrayed in all her charms, and more tremendous than ever.

This happened so often, that Mr Swiveller by degrees began to feel strange influences creeping over him—horrible desires to annihilate this Sally Brass—mysterious promptings to knock her head-dress off and try how she looked without it. There was a very large ruler on the table; a large, black, shining ruler. Mr Swiveller took it up and began to rub his nose with it.

From rubbing his nose with the ruler, to poising it in his hand and giving it an occasional flourish after the tomahawk manner, the transition was easy and natural. In some of these flourishes it went close to Miss Sally’s head; the ragged edges of the head-dress fluttered with the wind it raised; advance it but an inch, and that great brown knot was on the ground: yet still the unconscious maiden worked away, and never raised her eyes.

Well, this was a great relief. It was a good thing to write doggedly and obstinately until he was desperate, and then snatch up the ruler and whirl it about the brown head-dress with the consciousness that he could have it off if he liked. It was a good thing to draw it back, and rub his nose very hard with it, if he thought Miss Sally was going to look up, and to recompense himself with more hardy flourishes when he found she was still absorbed. By these means Mr Swiveller calmed the agitation of his feelings, until his applications to the ruler became less fierce and frequent, and he could even write as many as half-a-dozen consecutive lines without having recourse to it—which was a great victory.