As he was not one of those rough spirits who would strip fair Truth of every little shadowy vestment in which time and teeming fancies love to array her—and some of which become her pleasantly enough, serving, like the waters of her well, to add new graces to the charms they half conceal and half suggest, and to awaken interest and pursuit rather than languor and indifference—as, unlike this stern and obdurate class, he loved to see the goddess crowned with those garlands of wild flowers which tradition wreathes for her gentle wearing, and which are often freshest in their homeliest shapes—he trod with a light step and bore with a light hand upon the dust of centuries, unwilling to demolish any of the airy shrines that had been raised above it, if any good feeling or affection of the human heart were hiding thereabouts. Thus, in the case of an ancient coffin of rough stone, supposed, for many generations, to contain the bones of a certain baron, who, after ravaging, with cut, and thrust, and plunder, in foreign lands, came back with a penitent and sorrowing heart to die at home, but which had been lately shown by learned antiquaries to be no such thing, as the baron in question (so they contended) had died hard in battle, gnashing his teeth and cursing with his latest breath—the bachelor stoutly maintained that the old tale was the true one; that the baron, repenting him of the evil, had done great charities and meekly given up the ghost; and that, if ever baron went to heaven, that baron was then at peace. In like manner, when the aforesaid antiquaries did argue and contend that a certain secret vault was not the tomb of a grey-haired lady who had been hanged and drawn and quartered by glorious Queen Bess for succouring a wretched priest who fainted of thirst and hunger at her door, the bachelor did solemnly maintain, against all comers, that the church was hallowed by the said poor lady’s ashes; that her remains had been collected in the night from four of the city’s gates, and thither in secret brought, and there deposited; and the bachelor did further (being highly excited at such times) deny the glory of Queen Bess, and assert the immeasurably greater glory of the meanest woman in her realm, who had a merciful and tender heart. As to the assertion that the flat stone near the door was not the grave of the miser who had disowned his only child and left a sum of money to the church to buy a peal of bells, the bachelor did readily admit the same, and that the place had given birth to no such man. In a word, he would have had every stone, and plate of brass, the monument only of deeds whose memory should survive. All others he was willing to forget. They might be buried in consecrated ground, but he would have had them buried deep, and never brought to light again.

It was from the lips of such a tutor, that the child learnt her easy task. Already impressed, beyond all telling, by the silent building and the peaceful beauty of the spot in which it stood—majestic age surrounded by perpetual youth—it seemed to her, when she heard these things, sacred to all goodness and virtue. It was another world, where sin and sorrow never came; a tranquil place of rest, where nothing evil entered.

When the bachelor had given her in connection with almost every tomb and flat grave-stone some history of its own, he took her down into the old crypt, now a mere dull vault, and showed her how it had been lighted up in the time of the monks, and how, amid lamps depending from the roof, and swinging censers exhaling scented odours, and habits glittering with gold and silver, and pictures, and precious stuffs, and jewels all flashing and glistening through the low arches, the chaunt of aged voices had been many a time heard there, at midnight, in old days, while hooded figures knelt and prayed around, and told their rosaries of beads. Thence, he took her above ground again, and showed her, high up in the old walls, small galleries, where the nuns had been wont to glide along—dimly seen in their dark dresses so far off—or to pause like gloomy shadows, listening to the prayers. He showed her too, how the warriors, whose figures rested on the tombs, had worn those rotting scraps of armour up above—how this had been a helmet, and that a shield, and that a gauntlet—and how they had wielded the great two-handed swords, and beaten men down, with yonder iron mace. All that he told the child she treasured in her mind; and sometimes, when she awoke at night from dreams of those old times, and rising from her bed looked out at the dark church, she almost hoped to see the windows lighted up, and hear the organ’s swell, and sound of voices, on the rushing wind.

The old sexton soon got better, and was about again. From him the child learnt many other things, though of a different kind. He was not able to work, but one day there was a grave to be made, and he came to overlook the man who dug it. He was in a talkative mood; and the child, at first standing by his side, and afterwards sitting on the grass at his feet, with her thoughtful face raised towards his, began to converse with him.

Now, the man who did the sexton’s duty was a little older than he, though much more active. But he was deaf; and when the sexton (who peradventure, on a pinch, might have walked a mile with great difficulty in half-a-dozen hours) exchanged a remark with him about his work, the child could not help noticing that he did so with an impatient kind of pity for his infirmity, as if he were himself the strongest and heartiest man alive.

‘I’m sorry to see there is this to do,’ said the child when she approached. ‘I heard of no one having died.’

‘She lived in another hamlet, my dear,’ returned the sexton. ‘Three mile away.’

‘Was she young?’

‘Ye-yes’ said the sexton; not more than sixty-four, I think. David, was she more than sixty-four?’

David, who was digging hard, heard nothing of the question. The sexton, as he could not reach to touch him with his crutch, and was too infirm to rise without assistance, called his attention by throwing a little mould upon his red nightcap.

‘What’s the matter now?’ said David, looking up.

‘How old was Becky Morgan?’ asked the sexton.

‘Becky Morgan?’ repeated David.

‘Yes,’ replied the sexton; adding in a half compassionate, half irritable tone, which the old man couldn’t hear, ‘you’re getting very deaf, Davy, very deaf to be sure!’

The old man stopped in his work, and cleansing his spade with a piece of slate he had by him for the purpose—and scraping off, in the process, the essence of Heaven knows how many Becky Morgans—set himself to consider the subject.

‘Let me think’ quoth he. ‘I saw last night what they had put upon the coffin—was it seventy-nine?’

‘No, no,’ said the sexton.

‘Ah yes, it was though,’ returned the old man with a sigh. ‘For I remember thinking she was very near our age. Yes, it was seventy-nine.’

‘Are you sure you didn’t mistake a figure, Davy?’ asked the sexton, with signs of some emotion.

‘What?’ said the old man. ‘Say that again.’

‘He’s very deaf. He’s very deaf indeed,’ cried the sexton petulantly; ‘are you sure you’re right about the figures?’

‘Oh quite,’ replied the old man. ‘Why not?’

‘He’s exceedingly deaf,’ muttered the sexton to himself. ‘I think he’s getting foolish.’

The child rather wondered what had led him to this belief, as, to say the truth, the old man seemed quite as sharp as he, and was infinitely more robust. As the sexton said nothing more just then, however, she forgot it for the time, and spoke again.

‘You were telling me,’ she said, ‘about your gardening. Do you ever plant things here?’

‘In the churchyard?’ returned the sexton, ‘Not I.’

‘I have seen some flowers and little shrubs about,’ the child rejoined; ‘there are some over there, you see. I thought they were of your rearing, though indeed they grow but poorly.’

‘They grow as Heaven wills,’ said the old man; ‘and it kindly ordains that they shall never flourish here.’

‘I do not understand you.’

‘Why, this it is,’ said the sexton. ‘They mark the graves of those who had very tender, loving friends.’

‘I was sure they did!’ the child exclaimed. ‘I am very glad to know they do!’

‘Aye,’ returned the old man, ‘but stay. Look at them. See how they hang their heads, and droop, and wither. Do you guess the reason?’

‘No,’ the child replied.

‘Because the memory of those who lie below, passes away so soon. At first they tend them, morning, noon, and night; they soon begin to come less frequently; from once a day, to once a week; from once a week to once a month; then, at long and uncertain intervals; then, not at all. Such tokens seldom flourish long. I have known the briefest summer flowers outlive them.’

‘I grieve to hear it,’ said the child.

‘Ah! so say the gentlefolks who come down here to look about them,’ returned the old man, shaking his head, ‘but I say otherwise. “It’s a pretty custom you have in this part of the country,” they say to me sometimes, “to plant the graves, but it’s melancholy to see these things all withering or dead.” I crave their pardon and tell them that, as I take it, ‘tis a good sign for the happiness of the living. And so it is. It’s nature.’

‘Perhaps the mourners learn to look to the blue sky by day, and to the stars by night, and to think that the dead are there, and not in graves,’ said the child in an earnest voice.

‘Perhaps so,’ replied the old man doubtfully. ‘It may be.’

‘Whether it be as I believe it is, or no,’ thought the child within herself, ‘I’ll make this place my garden. It will be no harm at least to work here day by day, and pleasant thoughts will come of it, I am sure.’

Her glowing cheek and moistened eye passed unnoticed by the sexton, who turned towards old David, and called him by his name. It was plain that Becky Morgan’s age still troubled him; though why, the child could scarcely understand.

The second or third repetition of his name attracted the old man’s attention. Pausing from his work, he leant on his spade, and put his hand to his dull ear.

‘Did you call?’ he said.

‘I have been thinking, Davy,’ replied the sexton, ‘that she,’ he pointed to the grave, ‘must have been a deal older than you or me.’

‘Seventy-nine,’ answered the old man with a shake of the head, ‘I tell you that I saw it.’

‘Saw it?’ replied the sexton; ‘aye, but, Davy, women don’t always tell the truth about their age.’

‘That’s true indeed,’ said the other old man, with a sudden sparkle in his eye. ‘She might have been older.’

‘I’m sure she must have been. Why, only think how old she looked. You and I seemed but boys to her.’

‘She did look old,’ rejoined David. ‘You’re right. She did look old.’

‘Call to mind how old she looked for many a long, long year, and say if she could be but seventy-nine at last—only our age,’ said the sexton.

‘Five year older at the very least!’ cried the other.

‘Five!’ retorted the sexton. ‘Ten. Good eighty-nine. I call to mind the time her daughter died. She was eighty-nine if she was a day, and tries to pass upon us now, for ten year younger. Oh! human vanity!’

The other old man was not behindhand with some moral reflections on this fruitful theme, and both adduced a mass of evidence, of such weight as to render it doubtful—not whether the deceased was of the age suggested, but whether she had not almost reached the patriarchal term of a hundred. When they had settled this question to their mutual satisfaction, the sexton, with his friend’s assistance, rose to go.

‘It’s chilly, sitting here, and I must be careful—till the summer,’ he said, as he prepared to limp away.

‘What?’ asked old David.

‘He’s very deaf, poor fellow!’ cried the sexton. ‘Good-bye!’

'Ah!’ said old David, looking after him. ‘He’s failing very fast. He ages every day.’

And so they parted; each persuaded that the other had less life in him than himself; and both greatly consoled and comforted by the little fiction they had agreed upon, respecting Becky Morgan, whose decease was no longer a precedent of uncomfortable application, and would be no business of theirs for half a score of years to come.

The child remained, for some minutes, watching the deaf old man as he threw out the earth with his shovel, and, often stopping to cough and fetch his breath, still muttered to himself, with a kind of sober chuckle, that the sexton was wearing fast. At length she turned away, and walking thoughtfully through the churchyard, came unexpectedly upon the schoolmaster, who was sitting on a green grave in the sun, reading.

‘Nell here?’ he said cheerfully, as he closed his book. ‘It does me good to see you in the air and light. I feared you were again in the church, where you so often are.’

‘Feared!’ replied the child, sitting down beside him. ‘Is it not a good place?’

‘Yes, yes,’ said the schoolmaster. ‘But you must be gay sometimes—nay, don’t shake your head and smile so sadly.’

‘Not sadly, if you knew my heart. Do not look at me as if you thought me sorrowful. There is not a happier creature on earth, than I am now.’

Full of grateful tenderness, the child took his hand, and folded it between her own. ‘It’s God’s will!’ she said, when they had been silent for some time.

‘What?’

‘All this,’ she rejoined; ‘all this about us. But which of us is sad now? You see that I am smiling.’

‘And so am I,’ said the schoolmaster; ‘smiling to think how often we shall laugh in this same place. Were you not talking yonder?’

‘Yes,’the child rejoined.

‘Of something that has made you sorrowful?’

There was a long pause.

‘What was it?’ said the schoolmaster, tenderly. ‘Come. Tell me what it was.’

‘I rather grieve—I do rather grieve to think,’ said the child, bursting into tears, ‘that those who die about us, are so soon forgotten.’

‘And do you think,’ said the schoolmaster, marking the glance she had thrown around, ‘that an unvisited grave, a withered tree, a faded flower or two, are tokens of forgetfulness or cold neglect? Do you think there are no deeds, far away from here, in which these dead may be best remembered? Nell, Nell, there may be people busy in the world, at this instant, in whose good actions and good thoughts these very graves—neglected as they look to us—are the chief instruments.’

‘Tell me no more,’ said the child quickly. ‘Tell me no more. I feel, I know it. How could I be unmindful of it, when I thought of you?’

‘There is nothing,’ cried her friend, ‘no, nothing innocent or good, that dies, and is forgotten. Let us hold to that faith, or none. An infant, a prattling child, dying in its cradle, will live again in the better thoughts of those who loved it, and will play its part, through them, in the redeeming actions of the world, though its body be burnt to ashes or drowned in the deepest sea. There is not an angel added to the Host of Heaven but does its blessed work on earth in those that loved it here. Forgotten! oh, if the good deeds of human creatures could be traced to their source, how beautiful would even death appear; for how much charity, mercy, and purified affection, would be seen to have their growth in dusty graves!’

‘Yes,’ said the child, ‘it is the truth; I know it is. Who should feel its force so much as I, in whom your little scholar lives again! Dear, dear, good friend, if you knew the comfort you have given me!’

The poor schoolmaster made her no answer, but bent over her in silence; for his heart was full.

They were yet seated in the same place, when the grandfather approached. Before they had spoken many words together, the church clock struck the hour of school, and their friend withdrew.

‘A good man,’ said the grandfather, looking after him; ‘a kind man. Surely he will never harm us, Nell. We are safe here, at last, eh? We will never go away from here?’

The child shook her head and smiled.

‘She needs rest,’ said the old man, patting her cheek; ‘too pale—too pale. She is not like what she was.’

‘When?’ asked the child.

‘Ha!’ said the old man, ‘to be sure—when? How many weeks ago? Could I count them on my fingers? Let them rest though; they’re better gone.’

‘Much better, dear,’ replied the child. ‘We will forget them; or, if we ever call them to mind, it shall be only as some uneasy dream that has passed away.’

‘Hush!’ said the old man, motioning hastily to her with his hand and looking over his shoulder; ‘no more talk of the dream, and all the miseries it brought. There are no dreams here. ‘Tis a quiet place, and they keep away. Let us never think about them, lest they should pursue us again. Sunken eyes and hollow cheeks—wet, cold, and famine—and horrors before them all, that were even worse—we must forget such things if we would be tranquil here.’

‘Thank Heaven!’ inwardly exclaimed the child, ‘for this most happy change!’

‘I will be patient,’ said the old man, ‘humble, very thankful, and obedient, if you will let me stay. But do not hide from me; do not steal away alone; let me keep beside you. Indeed, I will be very true and faithful, Nell.’

‘I steal away alone! why that,’ replied the child, with assumed gaiety, ‘would be a pleasant jest indeed. See here, dear grandfather, we’ll make this place our garden—why not! It is a very good one—and to-morrow we’ll begin, and work together, side by side.’

‘It is a brave thought!’ cried her grandfather. ‘Mind, darling—we begin to-morrow!’

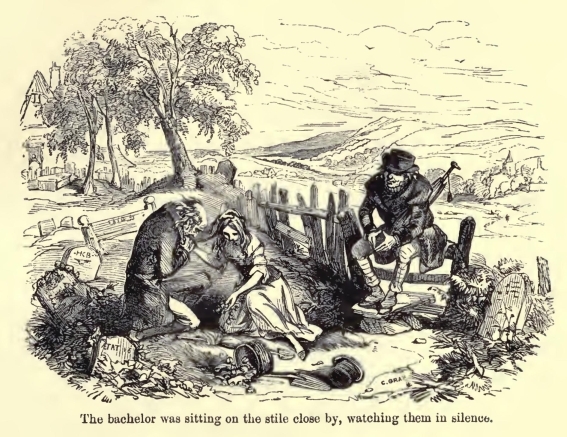

Who so delighted as the old man, when they next day began their labour! Who so unconscious of all associations connected with the spot, as he! They plucked the long grass and nettles from the tombs, thinned the poor shrubs and roots, made the turf smooth, and cleared it of the leaves and weeds. They were yet in the ardour of their work, when the child, raising her head from the ground over which she bent, observed that the bachelor was sitting on the stile close by, watching them in silence.

‘A kind office,’ said the little gentleman, nodding to Nell as she curtseyed to him. ‘Have you done all that, this morning?’

‘It is very little, sir,’ returned the child, with downcast eyes, ‘to what we mean to do.’

‘Good work, good work,’ said the bachelor. ‘But do you only labour at the graves of children, and young people?’

‘We shall come to the others in good time, sir,’ replied Nell, turning her head aside, and speaking softly.

It was a slight incident, and might have been design or accident, or the child’s unconscious sympathy with youth. But it seemed to strike upon her grandfather, though he had not noticed it before. He looked in a hurried manner at the graves, then anxiously at the child, then pressed her to his side, and bade her stop to rest. Something he had long forgotten, appeared to struggle faintly in his mind. It did not pass away, as weightier things had done; but came uppermost again, and yet again, and many times that day, and often afterwards. Once, while they were yet at work, the child, seeing that he often turned and looked uneasily at her, as though he were trying to resolve some painful doubts or collect some scattered thoughts, urged him to tell the reason. But he said it was nothing—nothing—and, laying her head upon his arm, patted her fair cheek with his hand, and muttered that she grew stronger every day, and would be a woman, soon.