Mrs Blimber and Miss Blimber came back in the Doctor’s company; and the Doctor, lifting his new pupil off the table, delivered him over to Miss Blimber.

“Cornelia,” said the Doctor, “Dombey will be your charge at first. Bring him on, Cornelia, bring him on.”

Miss Blimber received her young ward from the Doctor’s hands; and Paul, feeling that the spectacles were surveying him, cast down his eyes.

“How old are you, Dombey?” said Miss Blimber.

“Six,” answered Paul, wondering, as he stole a glance at the young lady, why her hair didn’t grow long like Florence’s, and why she was like a boy.

“How much do you know of your Latin Grammar, Dombey?” said Miss Blimber.

“None of it,” answered Paul. Feeling that the answer was a shock to Miss Blimber’s sensibility, he looked up at the three faces that were looking down at him, and said:

“I haven’t been well. I have been a weak child. I couldn’t learn a Latin Grammar when I was out, every day, with old Glubb. I wish you’d tell old Glubb to come and see me, if you please.”

“What a dreadfully low name” said Mrs Blimber. “Unclassical to a degree! Who is the monster, child?”

“What monster?” inquired Paul.

“Glubb,” said Mrs Blimber, with a great disrelish.

“He’s no more a monster than you are,” returned Paul.

“What!” cried the Doctor, in a terrible voice. “Ay, ay, ay? Aha! What’s that?”

Paul was dreadfully frightened; but still he made a stand for the absent Glubb, though he did it trembling.

“He’s a very nice old man, Ma’am,” he said. “He used to draw my couch. He knows all about the deep sea, and the fish that are in it, and the great monsters that come and lie on rocks in the sun, and dive into the water again when they’re startled, blowing and splashing so, that they can be heard for miles. There are some creatures, said Paul, warming with his subject, “I don’t know how many yards long, and I forget their names, but Florence knows, that pretend to be in distress; and when a man goes near them, out of compassion, they open their great jaws, and attack him. But all he has got to do,” said Paul, boldly tendering this information to the very Doctor himself, “is to keep on turning as he runs away, and then, as they turn slowly, because they are so long, and can’t bend, he’s sure to beat them. And though old Glubb don’t know why the sea should make me think of my Mama that’s dead, or what it is that it is always saying—always saying! he knows a great deal about it. And I wish,” the child concluded, with a sudden falling of his countenance, and failing in his animation, as he looked like one forlorn, upon the three strange faces, “that you’d let old Glubb come here to see me, for I know him very well, and he knows me.”

“Ha!” said the Doctor, shaking his head; “this is bad, but study will do much.”

Mrs Blimber opined, with something like a shiver, that he was an unaccountable child; and, allowing for the difference of visage, looked at him pretty much as Mrs Pipchin had been used to do.

“Take him round the house, Cornelia,” said the Doctor, “and familiarise him with his new sphere. Go with that young lady, Dombey.”

Dombey obeyed; giving his hand to the abstruse Cornelia, and looking at her sideways, with timid curiosity, as they went away together. For her spectacles, by reason of the glistening of the glasses, made her so mysterious, that he didn’t know where she was looking, and was not indeed quite sure that she had any eyes at all behind them.

Cornelia took him first to the schoolroom, which was situated at the back of the hall, and was approached through two baize doors, which deadened and muffled the young gentlemen’s voices. Here, there were eight young gentlemen in various stages of mental prostration, all very hard at work, and very grave indeed. Toots, as an old hand, had a desk to himself in one corner: and a magnificent man, of immense age, he looked, in Paul’s young eyes, behind it.

Mr Feeder, B.A., who sat at another little desk, had his Virgil stop on, and was slowly grinding that tune to four young gentlemen. Of the remaining four, two, who grasped their foreheads convulsively, were engaged in solving mathematical problems; one with his face like a dirty window, from much crying, was endeavouring to flounder through a hopeless number of lines before dinner; and one sat looking at his task in stony stupefaction and despair—which it seemed had been his condition ever since breakfast time.

The appearance of a new boy did not create the sensation that might have been expected. Mr Feeder, B.A. (who was in the habit of shaving his head for coolness, and had nothing but little bristles on it), gave him a bony hand, and told him he was glad to see him—which Paul would have been very glad to have told him, if he could have done so with the least sincerity. Then Paul, instructed by Cornelia, shook hands with the four young gentlemen at Mr Feeder’s desk; then with the two young gentlemen at work on the problems, who were very feverish; then with the young gentleman at work against time, who was very inky; and lastly with the young gentleman in a state of stupefaction, who was flabby and quite cold.

Paul having been already introduced to Toots, that pupil merely chuckled and breathed hard, as his custom was, and pursued the occupation in which he was engaged. It was not a severe one; for on account of his having “gone through” so much (in more senses than one), and also of his having, as before hinted, left off blowing in his prime, Toots now had licence to pursue his own course of study: which was chiefly to write long letters to himself from persons of distinction, adds “P. Toots, Esquire, Brighton, Sussex,” and to preserve them in his desk with great care.

These ceremonies passed, Cornelia led Paul upstairs to the top of the house; which was rather a slow journey, on account of Paul being obliged to land both feet on every stair, before he mounted another. But they reached their journey’s end at last; and there, in a front room, looking over the wild sea, Cornelia showed him a nice little bed with white hangings, close to the window, on which there was already beautifully written on a card in round text—down strokes very thick, and up strokes very fine—DOMBEY; while two other little bedsteads in the same room were announced, through like means, as respectively appertaining unto BRIGGS and TOZER.

Just as they got downstairs again into the hall, Paul saw the weak-eyed young man who had given that mortal offence to Mrs Pipchin, suddenly seize a very large drumstick, and fly at a gong that was hanging up, as if he had gone mad, or wanted vengeance. Instead of receiving warning, however, or being instantly taken into custody, the young man left off unchecked, after having made a dreadful noise. Then Cornelia Blimber said to Dombey that dinner would be ready in a quarter of an hour, and perhaps he had better go into the schoolroom among his “friends.”

So Dombey, deferentially passing the great clock which was still as anxious as ever to know how he found himself, opened the schoolroom door a very little way, and strayed in like a lost boy: shutting it after him with some difficulty. His friends were all dispersed about the room except the stony friend, who remained immoveable. Mr Feeder was stretching himself in his grey gown, as if, regardless of expense, he were resolved to pull the sleeves off.

“Heigh ho hum!” cried Mr Feeder, shaking himself like a cart-horse. “Oh dear me, dear me! Ya-a-a-ah!”

Paul was quite alarmed by Mr Feeder’s yawning; it was done on such a great scale, and he was so terribly in earnest. All the boys too (Toots excepted) seemed knocked up, and were getting ready for dinner—some newly tying their neckcloths, which were very stiff indeed; and others washing their hands or brushing their hair, in an adjoining ante-chamber—as if they didn’t think they should enjoy it at all.

Young Toots who was ready beforehand, and had therefore nothing to do, and had leisure to bestow upon Paul, said, with heavy good nature:

“Sit down, Dombey.”

“Thank you, Sir,” said Paul.

His endeavouring to hoist himself on to a very high window-seat, and his slipping down again, appeared to prepare Toots’s mind for the reception of a discovery.

“You’re a very small chap;” said Mr Toots.

“Yes, Sir, I’m small,” returned Paul. “Thank you, Sir.”

For Toots had lifted him into the seat, and done it kindly too.

“Who’s your tailor?” inquired Toots, after looking at him for some moments.

“It’s a woman that has made my clothes as yet,” said Paul. “My sister’s dressmaker.”

“My tailor’s Burgess and Co.,” said Toots. “Fash’nable. But very dear.”

Paul had wit enough to shake his head, as if he would have said it was easy to see that; and indeed he thought so.

“Your father’s regularly rich, ain’t he?” inquired Mr Toots.

“Yes, Sir,” said Paul. “He’s Dombey and Son.”

“And which?” demanded Toots.

“And Son, Sir,” replied Paul.

Mr Toots made one or two attempts, in a low voice, to fix the Firm in his mind; but not quite succeeding, said he would get Paul to mention the name again to-morrow morning, as it was rather important. And indeed he purposed nothing less than writing himself a private and confidential letter from Dombey and Son immediately.

By this time the other pupils (always excepting the stony boy) gathered round. They were polite, but pale; and spoke low; and they were so depressed in their spirits, that in comparison with the general tone of that company, Master Bitherstone was a perfect Miller, or complete Jest Book.” And yet he had a sense of injury upon him, too, had Bitherstone.

“You sleep in my room, don’t you?” asked a solemn young gentleman, whose shirt-collar curled up the lobes of his ears.

“Master Briggs?” inquired Paul.

“Tozer,” said the young gentleman.

Paul answered yes; and Tozer pointing out the stony pupil, said that was Briggs. Paul had already felt certain that it must be either Briggs or Tozer, though he didn’t know why.

“Is yours a strong constitution?” inquired Tozer.

Paul said he thought not. Tozer replied that he thought not also, judging from Paul’s looks, and that it was a pity, for it need be. He then asked Paul if he were going to begin with Cornelia; and on Paul saying “yes,” all the young gentlemen (Briggs excepted) gave a low groan.

It was drowned in the tintinnabulation of the gong, which sounding again with great fury, there was a general move towards the dining-room; still excepting Briggs the stony boy, who remained where he was, and as he was; and on its way to whom Paul presently encountered a round of bread, genteelly served on a plate and napkin, and with a silver fork lying crosswise on the top of it. Doctor Blimber was already in his place in the dining-room, at the top of the table, with Miss Blimber and Mrs Blimber on either side of him. Mr Feeder in a black coat was at the bottom. Paul’s chair was next to Miss Blimber; but it being found, when he sat in it, that his eyebrows were not much above the level of the table-cloth, some books were brought in from the Doctor’s study, on which he was elevated, and on which he always sat from that time— carrying them in and out himself on after occasions, like a little elephant and castle.

Grace having been said by the Doctor, dinner began. There was some nice soup; also roast meat, boiled meat, vegetables, pie, and cheese. Every young gentleman had a massive silver fork, and a napkin; and all the arrangements were stately and handsome. In particular, there was a butler in a blue coat and bright buttons, who gave quite a winey flavour to the table beer; he poured it out so superbly.

Nobody spoke, unless spoken to, except Doctor Blimber, Mrs Blimber, and Miss Blimber, who conversed occasionally. Whenever a young gentleman was not actually engaged with his knife and fork or spoon, his eye, with an irresistible attraction, sought the eye of Doctor Blimber, Mrs Blimber, or Miss Blimber, and modestly rested there. Toots appeared to be the only exception to this rule. He sat next Mr Feeder on Paul’s side of the table, and frequently looked behind and before the intervening boys to catch a glimpse of Paul.

Only once during dinner was there any conversation that included the young gentlemen. It happened at the epoch of the cheese, when the Doctor, having taken a glass of port wine, and hemmed twice or thrice, said:

“It is remarkable, Mr Feeder, that the Romans—”

At the mention of this terrible people, their implacable enemies, every young gentleman fastened his gaze upon the Doctor, with an assumption of the deepest interest. One of the number who happened to be drinking, and who caught the Doctor’s eye glaring at him through the side of his tumbler, left off so hastily that he was convulsed for some moments, and in the sequel ruined Doctor Blimber’s point.

“It is remarkable, Mr Feeder,” said the Doctor, beginning again slowly, “that the Romans, in those gorgeous and profuse entertainments of which we read in the days of the Emperors, when luxury had attained a height unknown before or since, and when whole provinces were ravaged to supply the splendid means of one Imperial Banquet—”

Here the offender, who had been swelling and straining, and waiting in vain for a full stop, broke out violently.

“Johnson,” said Mr Feeder, in a low reproachful voice, “take some water.”

The Doctor, looking very stern, made a pause until the water was brought, and then resumed:

“And when, Mr Feeder—”

But Mr Feeder, who saw that Johnson must break out again, and who knew that the Doctor would never come to a period before the young gentlemen until he had finished all he meant to say, couldn’t keep his eye off Johnson; and thus was caught in the fact of not looking at the Doctor, who consequently stopped.

“I beg your pardon, Sir,” said Mr Feeder, reddening. “I beg your pardon, Doctor Blimber.”

“And when,” said the Doctor, raising his voice, “when, Sir, as we read, and have no reason to doubt—incredible as it may appear to the vulgar—of our time—the brother of Vitellius prepared for him a feast, in which were served, of fish, two thousand dishes—”

“Take some water, Johnson—dishes, Sir,” said Mr Feeder.

“Of various sorts of fowl, five thousand dishes.”

“Or try a crust of bread,” said Mr Feeder.

“And one dish,” pursued Doctor Blimber, raising his voice still higher as he looked all round the table, “called, from its enormous dimensions, the Shield of Minerva, and made, among other costly ingredients, of the brains of pheasants—”

“Ow, ow, ow!” (from Johnson.)

“Woodcocks—”

“Ow, ow, ow!”

“The sounds of the fish called scari—”

“You’ll burst some vessel in your head,” said Mr Feeder. “You had better let it come.”

“And the spawn of the lamprey, brought from the Carpathian Sea,” pursued the Doctor, in his severest voice; “when we read of costly entertainments such as these, and still remember, that we have a Titus—”

“What would be your mother’s feelings if you died of apoplexy!” said Mr Feeder.

“A Domitian—”

“And you’re blue, you know,” said Mr Feeder.

“A Nero, a Tiberius, a Caligula, a Heliogabalus, and many more, pursued the Doctor; “it is, Mr Feeder—if you are doing me the honour to attend—remarkable; VERY remarkable, Sir—”

But Johnson, unable to suppress it any longer, burst at that moment into such an overwhelming fit of coughing, that although both his immediate neighbours thumped him on the back, and Mr Feeder himself held a glass of water to his lips, and the butler walked him up and down several times between his own chair and the sideboard, like a sentry, it was a full five minutes before he was moderately composed. Then there was a profound silence.

“Gentlemen,” said Doctor Blimber, “rise for Grace! Cornelia, lift Dombey down”—nothing of whom but his scalp was accordingly seen above the tablecloth. “Johnson will repeat to me tomorrow morning before breakfast, without book, and from the Greek Testament, the first chapter of the Epistle of Saint Paul to the Ephesians. We will resume our studies, Mr Feeder, in half-an-hour.”

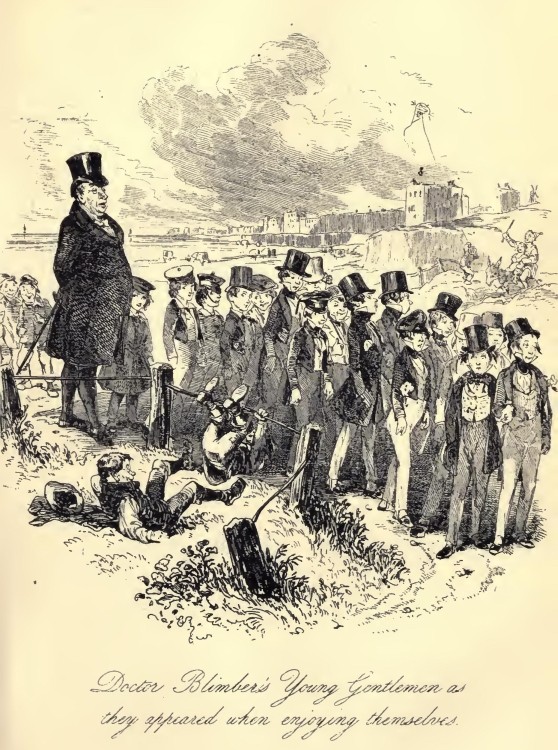

The young gentlemen bowed and withdrew. Mr Feeder did likewise. During the half-hour, the young gentlemen, broken into pairs, loitered arm-in-arm up and down a small piece of ground behind the house, or endeavoured to kindle a spark of animation in the breast of Briggs. But nothing happened so vulgar as play. Punctually at the appointed time, the gong was sounded, and the studies, under the joint auspices of Doctor Blimber and Mr Feeder, were resumed.

As the Olympic game of lounging up and down had been cut shorter than usual that day, on Johnson’s account, they all went out for a walk before tea. Even Briggs (though he hadn’t begun yet) partook of this dissipation; in the enjoyment of which he looked over the cliff two or three times darkly. Doctor Blimber accompanied them; and Paul had the honour of being taken in tow by the Doctor himself: a distinguished state of things, in which he looked very little and feeble.

Tea was served in a style no less polite than the dinner; and after tea, the young gentlemen rising and bowing as before, withdrew to fetch up the unfinished tasks of that day, or to get up the already looming tasks of to-morrow. In the meantime Mr Feeder withdrew to his own room; and Paul sat in a corner wondering whether Florence was thinking of him, and what they were all about at Mrs Pipchin’s.

Mr Toots, who had been detained by an important letter from the Duke of Wellington, found Paul out after a time; and having looked at him for a long while, as before, inquired if he was fond of waistcoats.

Paul said “Yes, Sir.”

“So am I,” said Toots.

No word more spoke Toots that night; but he stood looking at Paul as if he liked him; and as there was company in that, and Paul was not inclined to talk, it answered his purpose better than conversation.

At eight o’clock or so, the gong sounded again for prayers in the dining-room, where the butler afterwards presided over a side-table, on which bread and cheese and beer were spread for such young gentlemen as desired to partake of those refreshments. The ceremonies concluded by the Doctor’s saying, “Gentlemen, we will resume our studies at seven to-morrow;” and then, for the first time, Paul saw Cornelia Blimber’s eye, and saw that it was upon him. When the Doctor had said these words, “Gentlemen, we will resume our studies at seven tomorrow,” the pupils bowed again, and went to bed.

In the confidence of their own room upstairs, Briggs said his head ached ready to split, and that he should wish himself dead if it wasn’t for his mother, and a blackbird he had at home. Tozer didn’t say much, but he sighed a good deal, and told Paul to look out, for his turn would come to-morrow. After uttering those prophetic words, he undressed himself moodily, and got into bed. Briggs was in his bed too, and Paul in his bed too, before the weak-eyed young man appeared to take away the candle, when he wished them good-night and pleasant dreams. But his benevolent wishes were in vain, as far as Briggs and Tozer were concerned; for Paul, who lay awake for a long while, and often woke afterwards, found that Briggs was ridden by his lesson as a nightmare: and that Tozer, whose mind was affected in his sleep by similar causes, in a minor degree talked unknown tongues, or scraps of Greek and Latin—it was all one to Paul—which, in the silence of night, had an inexpressibly wicked and guilty effect.

Paul had sunk into a sweet sleep, and dreamed that he was walking hand in hand with Florence through beautiful gardens, when they came to a large sunflower which suddenly expanded itself into a gong, and began to sound. Opening his eyes, he found that it was a dark, windy morning, with a drizzling rain: and that the real gong was giving dreadful note of preparation, down in the hall.

So he got up directly, and found Briggs with hardly any eyes, for nightmare and grief had made his face puffy, putting his boots on: while Tozer stood shivering and rubbing his shoulders in a very bad humour. Poor Paul couldn’t dress himself easily, not being used to it, and asked them if they would have the goodness to tie some strings for him; but as Briggs merely said “Bother!” and Tozer, “Oh yes!” he went down when he was otherwise ready, to the next storey, where he saw a pretty young woman in leather gloves, cleaning a stove. The young woman seemed surprised at his appearance, and asked him where his mother was. When Paul told her she was dead, she took her gloves off, and did what he wanted; and furthermore rubbed his hands to warm them; and gave him a kiss; and told him whenever he wanted anything of that sort—meaning in the dressing way—to ask for “Melia; which Paul, thanking her very much, said he certainly would. He then proceeded softly on his journey downstairs, towards the room in which the young gentlemen resumed their studies, when, passing by a door that stood ajar, a voice from within cried, “Is that Dombey?” On Paul replying, “Yes, Ma’am:” for he knew the voice to be Miss Blimber’s: Miss Blimber said, “Come in, Dombey.” And in he went.

Miss Blimber presented exactly the appearance she had presented yesterday, except that she wore a shawl. Her little light curls were as crisp as ever, and she had already her spectacles on, which made Paul wonder whether she went to bed in them. She had a cool little sitting-room of her own up there, with some books in it, and no fire But Miss Blimber was never cold, and never sleepy.

Now, Dombey,” said Miss Blimber, “I am going out for a constitutional.”

Paul wondered what that was, and why she didn’t send the footman out to get it in such unfavourable weather. But he made no observation on the subject: his attention being devoted to a little pile of new books, on which Miss Blimber appeared to have been recently engaged.

“These are yours, Dombey,” said Miss Blimber.

“All of ’em, Ma’am?” said Paul.

“Yes,” returned Miss Blimber; “and Mr Feeder will look you out some more very soon, if you are as studious as I expect you will be, Dombey.”

“Thank you, Ma’am,” said Paul.

“I am going out for a constitutional,” resumed Miss Blimber; “and while I am gone, that is to say in the interval between this and breakfast, Dombey, I wish you to read over what I have marked in these books, and to tell me if you quite understand what you have got to learn. Don’t lose time, Dombey, for you have none to spare, but take them downstairs, and begin directly.”

“Yes, Ma’am,” answered Paul.

There were so many of them, that although Paul put one hand under the bottom book and his other hand and his chin on the top book, and hugged them all closely, the middle book slipped out before he reached the door, and then they all tumbled down on the floor. Miss Blimber said, “Oh, Dombey, Dombey, this is really very careless!” and piled them up afresh for him; and this time, by dint of balancing them with great nicety, Paul got out of the room, and down a few stairs before two of them escaped again. But he held the rest so tight, that he only left one more on the first floor, and one in the passage; and when he had got the main body down into the schoolroom, he set off upstairs again to collect the stragglers. Having at last amassed the whole library, and climbed into his place, he fell to work, encouraged by a remark from Tozer to the effect that he “was in for it now;” which was the only interruption he received till breakfast time. At that meal, for which he had no appetite, everything was quite as solemn and genteel as at the others; and when it was finished, he followed Miss Blimber upstairs.

“Now, Dombey,” said Miss Blimber. “How have you got on with those books?”

They comprised a little English, and a deal of Latin—names of things, declensions of articles and substantives, exercises thereon, and preliminary rules—a trifle of orthography, a glance at ancient history, a wink or two at modern ditto, a few tables, two or three weights and measures, and a little general information. When poor Paul had spelt out number two, he found he had no idea of number one; fragments whereof afterwards obtruded themselves into number three, which slided into number four, which grafted itself on to number two. So that whether twenty Romuluses made a Remus, or hic haec hoc was troy weight, or a verb always agreed with an ancient Briton, or three times four was Taurus a bull, were open questions with him.

“Oh, Dombey, Dombey!” said Miss Blimber, “this is very shocking.”

“If you please,” said Paul, “I think if I might sometimes talk a little to old Glubb, I should be able to do better.”

“Nonsense, Dombey,” said Miss Blimber. “I couldn’t hear of it. This is not the place for Glubbs of any kind. You must take the books down, I suppose, Dombey, one by one, and perfect yourself in the day’s instalment of subject A, before you turn at all to subject B. I am sorry to say, Dombey, that your education appears to have been very much neglected.”

“So Papa says,” returned Paul; “but I told you—I have been a weak child. Florence knows I have. So does Wickam.”

“Who is Wickam?” asked Miss Blimber.

“She has been my nurse,” Paul answered.

“I must beg you not to mention Wickam to me, then,” said Miss Blimber. “I couldn’t allow it”.

“You asked me who she was,” said Paul.

“Very well,” returned Miss Blimber; “but this is all very different indeed from anything of that sort, Dombey, and I couldn’t think of permitting it. As to having been weak, you must begin to be strong. And now take away the top book, if you please, Dombey, and return when you are master of the theme.”

Miss Blimber expressed her opinions on the subject of Paul’s uninstructed state with a gloomy delight, as if she had expected this result, and were glad to find that they must be in constant communication. Paul withdrew with the top task, as he was told, and laboured away at it, down below: sometimes remembering every word of it, and sometimes forgetting it all, and everything else besides: until at last he ventured upstairs again to repeat the lesson, when it was nearly all driven out of his head before he began, by Miss Blimber’s shutting up the book, and saying, “Go on, Dombey!” a proceeding so suggestive of the knowledge inside of her, that Paul looked upon the young lady with consternation, as a kind of learned Guy Fawkes, or artificial Bogle, stuffed full of scholastic straw.

He acquitted himself very well, nevertheless; and Miss Blimber, commending him as giving promise of getting on fast, immediately provided him with subject B; from which he passed to C, and even D before dinner. It was hard work, resuming his studies, soon after dinner; and he felt giddy and confused and drowsy and dull. But all the other young gentlemen had similar sensations, and were obliged to resume their studies too, if there were any comfort in that. It was a wonder that the great clock in the hall, instead of being constant to its first inquiry, never said, “Gentlemen, we will now resume our studies,” for that phrase was often enough repeated in its neighbourhood. The studies went round like a mighty wheel, and the young gentlemen were always stretched upon it.

After tea there were exercises again, and preparations for next day by candlelight. And in due course there was bed; where, but for that resumption of the studies which took place in dreams, were rest and sweet forgetfulness.

Oh Saturdays! Oh happy Saturdays, when Florence always came at noon, and never would, in any weather, stay away, though Mrs Pipchin snarled and growled, and worried her bitterly. Those Saturdays were Sabbaths for at least two little Christians among all the Jews, and did the holy Sabbath work of strengthening and knitting up a brother’s and a sister’s love.

Not even Sunday nights—the heavy Sunday nights, whose shadow darkened the first waking burst of light on Sunday mornings—could mar those precious Saturdays. Whether it was the great sea-shore, where they sat, and strolled together; or whether it was only Mrs Pipchin’s dull back room, in which she sang to him so softly, with his drowsy head upon her arm; Paul never cared. It was Florence. That was all he thought of. So, on Sunday nights, when the Doctor’s dark door stood agape to swallow him up for another week, the time was come for taking leave of Florence; no one else.

Mrs Wickam had been drafted home to the house in town, and Miss Nipper, now a smart young woman, had come down. To many a single combat with Mrs Pipchin, did Miss Nipper gallantly devote herself, and if ever Mrs Pipchin in all her life had found her match, she had found it now. Miss Nipper threw away the scabbard the first morning she arose in Mrs Pipchin’s house. She asked and gave no quarter. She said it must be war, and war it was; and Mrs Pipchin lived from that time in the midst of surprises, harassings, and defiances, and skirmishing attacks that came bouncing in upon her from the passage, even in unguarded moments of chops, and carried desolation to her very toast.

Miss Nipper had returned one Sunday night with Florence, from walking back with Paul to the Doctor’s, when Florence took from her bosom a little piece of paper, on which she had pencilled down some words.

“See here, Susan,” she said. “These are the names of the little books that Paul brings home to do those long exercises with, when he is so tired. I copied them last night while he was writing.”

“Don’t show ’em to me, Miss Floy, if you please,” returned Nipper, “I’d as soon see Mrs Pipchin.”

“I want you to buy them for me, Susan, if you will, tomorrow morning. I have money enough,” said Florence.

“Why, goodness gracious me, Miss Floy,” returned Miss Nipper, “how can you talk like that, when you have books upon books already, and masterses and mississes a teaching of you everything continual, though my belief is that your Pa, Miss Dombey, never would have learnt you nothing, never would have thought of it, unless you’d asked him—when he couldn’t well refuse; but giving consent when asked, and offering when unasked, Miss, is quite two things; I may not have my objections to a young man’s keeping company with me, and when he puts the question, may say ‘yes,’ but that’s not saying ‘would you be so kind as like me.’”

“But you can buy me the books, Susan; and you will, when you know why I want them.”

“Well, Miss, and why do you want ’em?” replied Nipper; adding, in a lower voice, “If it was to fling at Mrs Pipchin’s head, I’d buy a cart-load.”

“Paul has a great deal too much to do, Susan,” said Florence, “I am sure of it.”

“And well you may be, Miss,” returned her maid, “and make your mind quite easy that the willing dear is worked and worked away. If those is Latin legs,” exclaimed Miss Nipper, with strong feeling—in allusion to Paul’s; “give me English ones.”

“I am afraid he feels lonely and lost at Doctor Blimber’s, Susan,” pursued Florence, turning away her face.

“Ah,” said Miss Nipper, with great sharpness, “Oh, them ‘Blimbers’”

“Don’t blame anyone,” said Florence. “It’s a mistake.”

“I say nothing about blame, Miss,” cried Miss Nipper, “for I know that you object, but I may wish, Miss, that the family was set to work to make new roads, and that Miss Blimber went in front and had the pickaxe.”

After this speech, Miss Nipper, who was perfectly serious, wiped her eyes.

“I think I could perhaps give Paul some help, Susan, if I had these books,” said Florence, “and make the coming week a little easier to him. At least I want to try. So buy them for me, dear, and I will never forget how kind it was of you to do it!”

It must have been a harder heart than Susan Nipper’s that could have rejected the little purse Florence held out with these words, or the gentle look of entreaty with which she seconded her petition. Susan put the purse in her pocket without reply, and trotted out at once upon her errand.

The books were not easy to procure; and the answer at several shops was, either that they were just out of them, or that they never kept them, or that they had had a great many last month, or that they expected a great many next week But Susan was not easily baffled in such an enterprise; and having entrapped a white-haired youth, in a black calico apron, from a library where she was known, to accompany her in her quest, she led him such a life in going up and down, that he exerted himself to the utmost, if it were only to get rid of her; and finally enabled her to return home in triumph.

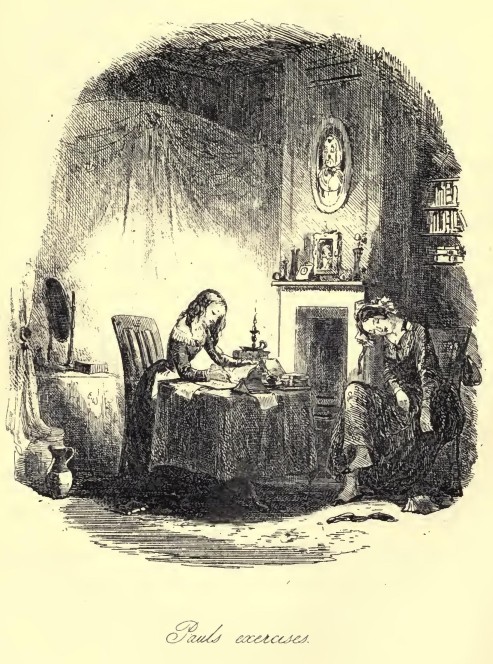

With these treasures then, after her own daily lessons were over, Florence sat down at night to track Paul’s footsteps through the thorny ways of learning; and being possessed of a naturally quick and sound capacity, and taught by that most wonderful of masters, love, it was not long before she gained upon Paul’s heels, and caught and passed him.

Not a word of this was breathed to Mrs Pipchin: but many a night when they were all in bed, and when Miss Nipper, with her hair in papers and herself asleep in some uncomfortable attitude, reposed unconscious by her side; and when the chinking ashes in the grate were cold and grey; and when the candles were burnt down and guttering out;—Florence tried so hard to be a substitute for one small Dombey, that her fortitude and perseverance might have almost won her a free right to bear the name herself.

And high was her reward, when one Saturday evening, as little Paul was sitting down as usual to “resume his studies,” she sat down by his side, and showed him all that was so rough, made smooth, and all that was so dark, made clear and plain, before him. It was nothing but a startled look in Paul’s wan face—a flush—a smile—and then a close embrace—but God knows how her heart leapt up at this rich payment for her trouble.

“Oh, Floy!” cried her brother, “how I love you! How I love you, Floy!”

“And I you, dear!”

“Oh! I am sure of that, Floy.”

He said no more about it, but all that evening sat close by her, very quiet; and in the night he called out from his little room within hers, three or four times, that he loved her.

Regularly, after that, Florence was prepared to sit down with Paul on Saturday night, and patiently assist him through so much as they could anticipate together of his next week’s work. The cheering thought that he was labouring on where Florence had just toiled before him, would, of itself, have been a stimulant to Paul in the perpetual resumption of his studies; but coupled with the actual lightening of his load, consequent on this assistance, it saved him, possibly, from sinking underneath the burden which the fair Cornelia Blimber piled upon his back.

It was not that Miss Blimber meant to be too hard upon him, or that Doctor Blimber meant to bear too heavily on the young gentlemen in general. Cornelia merely held the faith in which she had been bred; and the Doctor, in some partial confusion of his ideas, regarded the young gentlemen as if they were all Doctors, and were born grown up. Comforted by the applause of the young gentlemen’s nearest relations, and urged on by their blind vanity and ill-considered haste, it would have been strange if Doctor Blimber had discovered his mistake, or trimmed his swelling sails to any other tack.

Thus in the case of Paul. When Doctor Blimber said he made great progress and was naturally clever, Mr Dombey was more bent than ever on his being forced and crammed. In the case of Briggs, when Doctor Blimber reported that he did not make great progress yet, and was not naturally clever, Briggs senior was inexorable in the same purpose. In short, however high and false the temperature at which the Doctor kept his hothouse, the owners of the plants were always ready to lend a helping hand at the bellows, and to stir the fire.

Such spirits as he had in the outset, Paul soon lost of course. But he retained all that was strange, and old, and thoughtful in his character: and under circumstances so favourable to the development of those tendencies, became even more strange, and old, and thoughtful, than before.

The only difference was, that he kept his character to himself. He grew more thoughtful and reserved, every day; and had no such curiosity in any living member of the Doctor’s household, as he had had in Mrs Pipchin. He loved to be alone; and in those short intervals when he was not occupied with his books, liked nothing so well as wandering about the house by himself, or sitting on the stairs, listening to the great clock in the hall. He was intimate with all the paperhanging in the house; saw things that no one else saw in the patterns; found out miniature tigers and lions running up the bedroom walls, and squinting faces leering in the squares and diamonds of the floor-cloth.

The solitary child lived on, surrounded by this arabesque work of his musing fancy, and no one understood him. Mrs Blimber thought him “odd,” and sometimes the servants said among themselves that little Dombey “moped;” but that was all.

Unless young Toots had some idea on the subject, to the expression of which he was wholly unequal. Ideas, like ghosts (according to the common notion of ghosts), must be spoken to a little before they will explain themselves; and Toots had long left off asking any questions of his own mind. Some mist there may have been, issuing from that leaden casket, his cranium, which, if it could have taken shape and form, would have become a genie; but it could not; and it only so far followed the example of the smoke in the Arabian story, as to roll out in a thick cloud, and there hang and hover. But it left a little figure visible upon a lonely shore, and Toots was always staring at it.

“How are you?” he would say to Paul, fifty times a day. “Quite well, Sir, thank you,” Paul would answer. “Shake hands,” would be Toots’s next advance.

Which Paul, of course, would immediately do. Mr Toots generally said again, after a long interval of staring and hard breathing, “How are you?” To which Paul again replied, “Quite well, Sir, thank you.”

One evening Mr Toots was sitting at his desk, oppressed by correspondence, when a great purpose seemed to flash upon him. He laid down his pen, and went off to seek Paul, whom he found at last, after a long search, looking through the window of his little bedroom.

“I say!” cried Toots, speaking the moment he entered the room, lest he should forget it; “what do you think about?”

“Oh! I think about a great many things,” replied Paul.

“Do you, though?” said Toots, appearing to consider that fact in itself surprising. “If you had to die,” said Paul, looking up into his face—Mr Toots started, and seemed much disturbed.

“Don’t you think you would rather die on a moonlight night, when the sky was quite clear, and the wind blowing, as it did last night?”

Mr Toots said, looking doubtfully at Paul, and shaking his head, that he didn’t know about that.

“Not blowing, at least,” said Paul, “but sounding in the air like the sea sounds in the shells. It was a beautiful night. When I had listened to the water for a long time, I got up and looked out. There was a boat over there, in the full light of the moon; a boat with a sail.”

The child looked at him so steadfastly, and spoke so earnestly, that Mr Toots, feeling himself called upon to say something about this boat, said, “Smugglers.” But with an impartial remembrance of there being two sides to every question, he added, “or Preventive.”

“A boat with a sail,” repeated Paul, “in the full light of the moon. The sail like an arm, all silver. It went away into the distance, and what do you think it seemed to do as it moved with the waves?”

“Pitch,” said Mr Toots.

“It seemed to beckon,” said the child, “to beckon me to come!—There she is! There she is!”

Toots was almost beside himself with dismay at this sudden exclamation, after what had gone before, and cried “Who?”

“My sister Florence!” cried Paul, “looking up here, and waving her hand. She sees me—she sees me! Good-night, dear, good-night, good-night.”

His quick transition to a state of unbounded pleasure, as he stood at his window, kissing and clapping his hands: and the way in which the light retreated from his features as she passed out of his view, and left a patient melancholy on the little face: were too remarkable wholly to escape even Toots’s notice. Their interview being interrupted at this moment by a visit from Mrs Pipchin, who usually brought her black skirts to bear upon Paul just before dusk, once or twice a week, Toots had no opportunity of improving the occasion: but it left so marked an impression on his mind that he twice returned, after having exchanged the usual salutations, to ask Mrs Pipchin how she did. This the irascible old lady conceived to be a deeply devised and long-meditated insult, originating in the diabolical invention of the weak-eyed young man downstairs, against whom she accordingly lodged a formal complaint with Doctor Blimber that very night; who mentioned to the young man that if he ever did it again, he should be obliged to part with him.

The evenings being longer now, Paul stole up to his window every evening to look out for Florence. She always passed and repassed at a certain time, until she saw him; and their mutual recognition was a gleam of sunshine in Paul’s daily life. Often after dark, one other figure walked alone before the Doctor’s house. He rarely joined them on the Saturdays now. He could not bear it. He would rather come unrecognised, and look up at the windows where his son was qualifying for a man; and wait, and watch, and plan, and hope.

Oh! could he but have seen, or seen as others did, the slight spare boy above, watching the waves and clouds at twilight, with his earnest eyes, and breasting the window of his solitary cage when birds flew by, as if he would have emulated them, and soared away!