Whether Miss Tox conceived that having been selected by the Fates to welcome the little Dombey before he was born, in Kirby, Beard and Kirby’s Best Mixed Pins, it therefore naturally devolved upon her to greet him with all other forms of welcome in all other early stages of his existence—or whether her overflowing goodness induced her to volunteer into the domestic militia as a substitute in some sort for his deceased Mama—or whether she was conscious of any other motives—are questions which in this stage of the Firm’s history herself only could have solved. Nor have they much bearing on the fact (of which there is no doubt), that Miss Tox’s constancy and zeal were a heavy discouragement to Richards, who lost flesh hourly under her patronage, and was in some danger of being superintended to death.

Miss Tox was often in the habit of assuring Mrs Chick, that nothing could exceed her interest in all connected with the development of that sweet child; and an observer of Miss Tox’s proceedings might have inferred so much without declaratory confirmation. She would preside over the innocent repasts of the young heir, with ineffable satisfaction, almost with an air of joint proprietorship with Richards in the entertainment. At the little ceremonies of the bath and toilette, she assisted with enthusiasm. The administration of infantine doses of physic awakened all the active sympathy of her character; and being on one occasion secreted in a cupboard (whither she had fled in modesty), when Mr Dombey was introduced into the nursery by his sister, to behold his son, in the course of preparation for bed, taking a short walk uphill over Richards’s gown, in a short and airy linen jacket, Miss Tox was so transported beyond the ignorant present as to be unable to refrain from crying out, “Is he not beautiful Mr Dombey! Is he not a Cupid, Sir!” and then almost sinking behind the closet door with confusion and blushes.

“Louisa,” said Mr Dombey, one day, to his sister, “I really think I must present your friend with some little token, on the occasion of Paul’s christening. She has exerted herself so warmly in the child’s behalf from the first, and seems to understand her position so thoroughly (a very rare merit in this world, I am sorry to say), that it would really be agreeable to me to notice her.”

Let it be no detraction from the merits of Miss Tox, to hint that in Mr Dombey’s eyes, as in some others that occasionally see the light, they only achieved that mighty piece of knowledge, the understanding of their own position, who showed a fitting reverence for his. It was not so much their merit that they knew themselves, as that they knew him, and bowed low before him.

“My dear Paul,” returned his sister, “you do Miss Tox but justice, as a man of your penetration was sure, I knew, to do. I believe if there are three words in the English language for which she has a respect amounting almost to veneration, those words are, Dombey and Son.”

“Well,” said Mr Dombey, “I believe it. It does Miss Tox credit.”

“And as to anything in the shape of a token, my dear Paul,” pursued his sister, “all I can say is that anything you give Miss Tox will be hoarded and prized, I am sure, like a relic. But there is a way, my dear Paul, of showing your sense of Miss Tox’s friendliness in a still more flattering and acceptable manner, if you should be so inclined.”

“How is that?” asked Mr Dombey.

“Godfathers, of course,” continued Mrs Chick, “are important in point of connexion and influence.”

“I don’t know why they should be, to my son,” said Mr Dombey, coldly.

“Very true, my dear Paul,” retorted Mrs Chick, with an extraordinary show of animation, to cover the suddenness of her conversion; “and spoken like yourself. I might have expected nothing else from you. I might have known that such would have been your opinion. Perhaps;” here Mrs Chick faltered again, as not quite comfortably feeling her way; “perhaps that is a reason why you might have the less objection to allowing Miss Tox to be godmother to the dear thing, if it were only as deputy and proxy for someone else. That it would be received as a great honour and distinction, Paul, I need not say.”

“Louisa,” said Mr Dombey, after a short pause, “it is not to be supposed—”

“Certainly not,” cried Mrs Chick, hastening to anticipate a refusal, “I never thought it was.”

Mr Dombey looked at her impatiently.

“Don’t flurry me, my dear Paul,” said his sister; “for that destroys me. I am far from strong. I have not been quite myself, since poor dear Fanny departed.”

Mr Dombey glanced at the pocket-handkerchief which his sister applied to her eyes, and resumed:

“It is not be supposed, I say—”

“And I say,” murmured Mrs Chick, “that I never thought it was.”

“Good Heaven, Louisa!” said Mr Dombey.

“No, my dear Paul,” she remonstrated with tearful dignity, “I must really be allowed to speak. I am not so clever, or so reasoning, or so eloquent, or so anything, as you are. I know that very well. So much the worse for me. But if they were the last words I had to utter—and last words should be very solemn to you and me, Paul, after poor dear Fanny—I would still say I never thought it was. And what is more,” added Mrs Chick with increased dignity, as if she had withheld her crushing argument until now, “I never did think it was.”

Mr Dombey walked to the window and back again.

“It is not to be supposed, Louisa,” he said (Mrs Chick had nailed her colours to the mast, and repeated “I know it isn’t,” but he took no notice of it), “but that there are many persons who, supposing that I recognised any claim at all in such a case, have a claim upon me superior to Miss Tox’s. But I do not. I recognise no such thing. Paul and myself will be able, when the time comes, to hold our own—the House, in other words, will be able to hold its own, and maintain its own, and hand down its own of itself, and without any such common-place aids. The kind of foreign help which people usually seek for their children, I can afford to despise; being above it, I hope. So that Paul’s infancy and childhood pass away well, and I see him becoming qualified without waste of time for the career on which he is destined to enter, I am satisfied. He will make what powerful friends he pleases in after-life, when he is actively maintaining—and extending, if that is possible—the dignity and credit of the Firm. Until then, I am enough for him, perhaps, and all in all. I have no wish that people should step in between us. I would much rather show my sense of the obliging conduct of a deserving person like your friend. Therefore let it be so; and your husband and myself will do well enough for the other sponsors, I daresay.”

In the course of these remarks, delivered with great majesty and grandeur, Mr Dombey had truly revealed the secret feelings of his breast. An indescribable distrust of anybody stepping in between himself and his son; a haughty dread of having any rival or partner in the boy’s respect and deference; a sharp misgiving, recently acquired, that he was not infallible in his power of bending and binding human wills; as sharp a jealousy of any second check or cross; these were, at that time the master keys of his soul. In all his life, he had never made a friend. His cold and distant nature had neither sought one, nor found one. And now, when that nature concentrated its whole force so strongly on a partial scheme of parental interest and ambition, it seemed as if its icy current, instead of being released by this influence, and running clear and free, had thawed for but an instant to admit its burden, and then frozen with it into one unyielding block.

Elevated thus to the godmothership of little Paul, in virtue of her insignificance, Miss Tox was from that hour chosen and appointed to office; and Mr Dombey further signified his pleasure that the ceremony, already long delayed, should take place without further postponement. His sister, who had been far from anticipating so signal a success, withdrew as soon as she could, to communicate it to her best of friends; and Mr Dombey was left alone in his library. He had already laid his hand upon the bellrope to convey his usual summons to Richards, when his eye fell upon a writing-desk, belonging to his deceased wife, which had been taken, among other things, from a cabinet in her chamber. It was not the first time that his eye had lighted on it He carried the key in his pocket; and he brought it to his table and opened it now—having previously locked the room door—with a well-accustomed hand.

From beneath a leaf of torn and cancelled scraps of paper, he took one letter that remained entire. Involuntarily holding his breath as he opened this document, and “bating in the stealthy action something of his arrogant demeanour, he sat down, resting his head upon one hand, and read it through.

He read it slowly and attentively, and with a nice particularity to every syllable. Otherwise than as his great deliberation seemed unnatural, and perhaps the result of an effort equally great, he allowed no sign of emotion to escape him. When he had read it through, he folded and refolded it slowly several times, and tore it carefully into fragments. Checking his hand in the act of throwing these away, he put them in his pocket, as if unwilling to trust them even to the chances of being re-united and deciphered; and instead of ringing, as usual, for little Paul, he sat solitary, all the evening, in his cheerless room.

There was anything but solitude in the nursery; for there, Mrs Chick and Miss Tox were enjoying a social evening, so much to the disgust of Miss Susan Nipper, that that young lady embraced every opportunity of making wry faces behind the door. Her feelings were so much excited on the occasion, that she found it indispensable to afford them this relief, even without having the comfort of any audience or sympathy whatever. As the knight-errants of old relieved their minds by carving their mistress’s names in deserts, and wildernesses, and other savage places where there was no probability of there ever being anybody to read them, so did Miss Susan Nipper curl her snub nose into drawers and wardrobes, put away winks of disparagement in cupboards, shed derisive squints into stone pitchers, and contradict and call names out in the passage.

The two interlopers, however, blissfully unconscious of the young lady’s sentiments, saw little Paul safe through all the stages of undressing, airy exercise, supper and bed; and then sat down to tea before the fire. The two children now lay, through the good offices of Polly, in one room; and it was not until the ladies were established at their tea-table that, happening to look towards the little beds, they thought of Florence.

“How sound she sleeps!” said Miss Tox.

“Why, you know, my dear, she takes a great deal of exercise in the course of the day,” returned Mrs Chick, “playing about little Paul so much.”

“She is a curious child,” said Miss Tox.

“My dear,” retorted Mrs Chick, in a low voice: “Her Mama, all over!”

“In-deed!” said Miss Tox. “Ah dear me!”

A tone of most extraordinary compassion Miss Tox said it in, though she had no distinct idea why, except that it was expected of her.

“Florence will never, never, never be a Dombey,” said Mrs Chick, “not if she lives to be a thousand years old.”

Miss Tox elevated her eyebrows, and was again full of commiseration.

“I quite fret and worry myself about her,” said Mrs Chick, with a sigh of modest merit. “I really don’t see what is to become of her when she grows older, or what position she is to take. She don’t gain on her Papa in the least. How can one expect she should, when she is so very unlike a Dombey?”

Miss Tox looked as if she saw no way out of such a cogent argument as that, at all.

“And the child, you see,” said Mrs Chick, in deep confidence, “has poor dear Fanny’s nature. She’ll never make an effort in after-life, I’ll venture to say. Never! She’ll never wind and twine herself about her Papa’s heart like—”

“Like the ivy?” suggested Miss Tox.

“Like the ivy,” Mrs Chick assented. “Never! She’ll never glide and nestle into the bosom of her Papa’s affections like—the—”

“Startled fawn?” suggested Miss Tox.

“Like the startled fawn,” said Mrs Chick. “Never! Poor Fanny! Yet, how I loved her!”

“You must not distress yourself, my dear,” said Miss Tox, in a soothing voice. “Now really! You have too much feeling.”

“We have all our faults,” said Mrs Chick, weeping and shaking her head. “I daresay we have. I never was blind to hers. I never said I was. Far from it. Yet how I loved her!”

What a satisfaction it was to Mrs Chick—a common-place piece of folly enough, compared with whom her sister-in-law had been a very angel of womanly intelligence and gentleness—to patronise and be tender to the memory of that lady: in exact pursuance of her conduct to her in her lifetime: and to thoroughly believe herself, and take herself in, and make herself uncommonly comfortable on the strength of her toleration! What a mighty pleasant virtue toleration should be when we are right, to be so very pleasant when we are wrong, and quite unable to demonstrate how we come to be invested with the privilege of exercising it!

Mrs Chick was yet drying her eyes and shaking her head, when Richards made bold to caution her that Miss Florence was awake and sitting in her bed. She had risen, as the nurse said, and the lashes of her eyes were wet with tears. But no one saw them glistening save Polly. No one else leant over her, and whispered soothing words to her, or was near enough to hear the flutter of her beating heart.

“Oh! dear nurse!” said the child, looking earnestly up in her face, “let me lie by my brother!”

“Why, my pet?” said Richards.

“Oh! I think he loves me,” cried the child wildly. “Let me lie by him. Pray do!”

Mrs Chick interposed with some motherly words about going to sleep like a dear, but Florence repeated her supplication, with a frightened look, and in a voice broken by sobs and tears.

“I’ll not wake him,” she said, covering her face and hanging down her head. “I’ll only touch him with my hand, and go to sleep. Oh, pray, pray, let me lie by my brother tonight, for I believe he’s fond of me!”

Richards took her without a word, and carrying her to the little bed in which the infant was sleeping, laid her down by his side. She crept as near him as she could without disturbing his rest; and stretching out one arm so that it timidly embraced his neck, and hiding her face on the other, over which her damp and scattered hair fell loose, lay motionless.

“Poor little thing,” said Miss Tox; “she has been dreaming, I daresay.”

Dreaming, perhaps, of loving tones for ever silent, of loving eyes for ever closed, of loving arms again wound round her, and relaxing in that dream within the dam which no tongue can relate. Seeking, perhaps—in dreams—some natural comfort for a heart, deeply and sorely wounded, though so young a child’s: and finding it, perhaps, in dreams, if not in waking, cold, substantial truth. This trivial incident had so interrupted the current of conversation, that it was difficult of resumption; and Mrs Chick moreover had been so affected by the contemplation of her own tolerant nature, that she was not in spirits. The two friends accordingly soon made an end of their tea, and a servant was despatched to fetch a hackney cabriolet for Miss Tox. Miss Tox had great experience in hackney cabs, and her starting in one was generally a work of time, as she was systematic in the preparatory arrangements.

“Have the goodness, if you please, Towlinson,” said Miss Tox, “first of all, to carry out a pen and ink and take his number legibly.”

“Yes, Miss,” said Towlinson.

“Then, if you please, Towlinson,” said Miss Tox, “have the goodness to turn the cushion. Which,” said Miss Tox apart to Mrs Chick, “is generally damp, my dear.”

“Yes, Miss,” said Towlinson.

“I’ll trouble you also, if you please, Towlinson,” said Miss Tox, “with this card and this shilling. He’s to drive to the card, and is to understand that he will not on any account have more than the shilling.”

“No, Miss,” said Towlinson.

“And—I’m sorry to give you so much trouble, Towlinson,” said Miss Tox, looking at him pensively.

“Not at all, Miss,” said Towlinson.

“Mention to the man, then, if you please, Towlinson,” said Miss Tox, “that the lady’s uncle is a magistrate, and that if he gives her any of his impertinence he will be punished terribly. You can pretend to say that, if you please, Towlinson, in a friendly way, and because you know it was done to another man, who died.”

“Certainly, Miss,” said Towlinson.

“And now good-night to my sweet, sweet, sweet, godson,” said Miss Tox, with a soft shower of kisses at each repetition of the adjective; “and Louisa, my dear friend, promise me to take a little something warm before you go to bed, and not to distress yourself!”

It was with extreme difficulty that Nipper, the black-eyed, who looked on steadfastly, contained herself at this crisis, and until the subsequent departure of Mrs Chick. But the nursery being at length free of visitors, she made herself some recompense for her late restraint.

“You might keep me in a strait-waistcoat for six weeks,” said Nipper, “and when I got it off I’d only be more aggravated, who ever heard the like of them two Griffins, Mrs Richards?”

“And then to talk of having been dreaming, poor dear!” said Polly.

“Oh you beauties!” cried Susan Nipper, affecting to salute the door by which the ladies had departed. “Never be a Dombey won’t she? It’s to be hoped she won’t, we don’t want any more such, one’s enough.”

“Don’t wake the children, Susan dear,” said Polly.

“I’m very much beholden to you, Mrs Richards,” said Susan, who was not by any means discriminating in her wrath, “and really feel it as a honour to receive your commands, being a black slave and a mulotter. Mrs Richards, if there’s any other orders, you can give me, pray mention ’em.”

“Nonsense; orders,” said Polly.

“Oh! bless your heart, Mrs Richards,” cried Susan, “temporaries always orders permanencies here, didn’t you know that, why wherever was you born, Mrs Richards? But wherever you was born, Mrs Richards,” pursued Spitfire, shaking her head resolutely, “and whenever, and however (which is best known to yourself), you may bear in mind, please, that it’s one thing to give orders, and quite another thing to take ’em. A person may tell a person to dive off a bridge head foremost into five-and-forty feet of water, Mrs Richards, but a person may be very far from diving.”

“There now,” said Polly, “you’re angry because you’re a good little thing, and fond of Miss Florence; and yet you turn round on me, because there’s nobody else.”

“It’s very easy for some to keep their tempers, and be soft-spoken, Mrs Richards,” returned Susan, slightly mollified, “when their child’s made as much of as a prince, and is petted and patted till it wishes its friends further, but when a sweet young pretty innocent, that never ought to have a cross word spoken to or of it, is rundown, the case is very different indeed. My goodness gracious me, Miss Floy, you naughty, sinful child, if you don’t shut your eyes this minute, I’ll call in them hobgoblins that lives in the cock-loft to come and eat you up alive!”

Here Miss Nipper made a horrible lowing, supposed to issue from a conscientious goblin of the bull species, impatient to discharge the severe duty of his position. Having further composed her young charge by covering her head with the bedclothes, and making three or four angry dabs at the pillow, she folded her arms, and screwed up her mouth, and sat looking at the fire for the rest of the evening.

Though little Paul was said, in nursery phrase, “to take a deal of notice for his age,” he took as little notice of all this as of the preparations for his christening on the next day but one; which nevertheless went on about him, as to his personal apparel, and that of his sister and the two nurses, with great activity. Neither did he, on the arrival of the appointed morning, show any sense of its importance; being, on the contrary, unusually inclined to sleep, and unusually inclined to take it ill in his attendants that they dressed him to go out.

It happened to be an iron-grey autumnal day, with a shrewd east wind blowing—a day in keeping with the proceedings. Mr Dombey represented in himself the wind, the shade, and the autumn of the christening. He stood in his library to receive the company, as hard and cold as the weather; and when he looked out through the glass room, at the trees in the little garden, their brown and yellow leaves came fluttering down, as if he blighted them.

Ugh! They were black, cold rooms; and seemed to be in mourning, like the inmates of the house. The books precisely matched as to size, and drawn up in line, like soldiers, looked in their cold, hard, slippery uniforms, as if they had but one idea among them, and that was a freezer. The bookcase, glazed and locked, repudiated all familiarities. Mr Pitt, in bronze, on the top, with no trace of his celestial origin about him, guarded the unattainable treasure like an enchanted Moor. A dusty urn at each high corner, dug up from an ancient tomb, preached desolation and decay, as from two pulpits; and the chimney-glass, reflecting Mr Dombey and his portrait at one blow, seemed fraught with melancholy meditations.

The stiff and stark fire-irons appeared to claim a nearer relationship than anything else there to Mr Dombey, with his buttoned coat, his white cravat, his heavy gold watch-chain, and his creaking boots. But this was before the arrival of Mr and Mrs Chick, his lawful relatives, who soon presented themselves.

“My dear Paul,” Mrs Chick murmured, as she embraced him, “the beginning, I hope, of many joyful days!”

“Thank you, Louisa,” said Mr Dombey, grimly. “How do you do, Mr John?”

“How do you do, Sir?” said Chick.

He gave Mr Dombey his hand, as if he feared it might electrify him. Mr Dombey took it as if it were a fish, or seaweed, or some such clammy substance, and immediately returned it to him with exalted politeness.

“Perhaps, Louisa,” said Mr Dombey, slightly turning his head in his cravat, as if it were a socket, “you would have preferred a fire?”

“Oh, my dear Paul, no,” said Mrs Chick, who had much ado to keep her teeth from chattering; “not for me.”

“Mr John,” said Mr Dombey, “you are not sensible of any chill?”

Mr John, who had already got both his hands in his pockets over the wrists, and was on the very threshold of that same canine chorus which had given Mrs Chick so much offence on a former occasion, protested that he was perfectly comfortable.

He added in a low voice, “With my tiddle tol toor rul”—when he was providentially stopped by Towlinson, who announced:

“Miss Tox!”

And enter that fair enslaver, with a blue nose and indescribably frosty face, referable to her being very thinly clad in a maze of fluttering odds and ends, to do honour to the ceremony.

“How do you do, Miss Tox?” said Mr Dombey.

Miss Tox, in the midst of her spreading gauzes, went down altogether like an opera-glass shutting-up; she curtseyed so low, in acknowledgment of Mr Dombey’s advancing a step or two to meet her.

“I can never forget this occasion, Sir,” said Miss Tox, softly. “’Tis impossible. My dear Louisa, I can hardly believe the evidence of my senses.”

If Miss Tox could believe the evidence of one of her senses, it was a very cold day. That was quite clear. She took an early opportunity of promoting the circulation in the tip of her nose by secretly chafing it with her pocket handkerchief, lest, by its very low temperature, it should disagreeably astonish the baby when she came to kiss it.

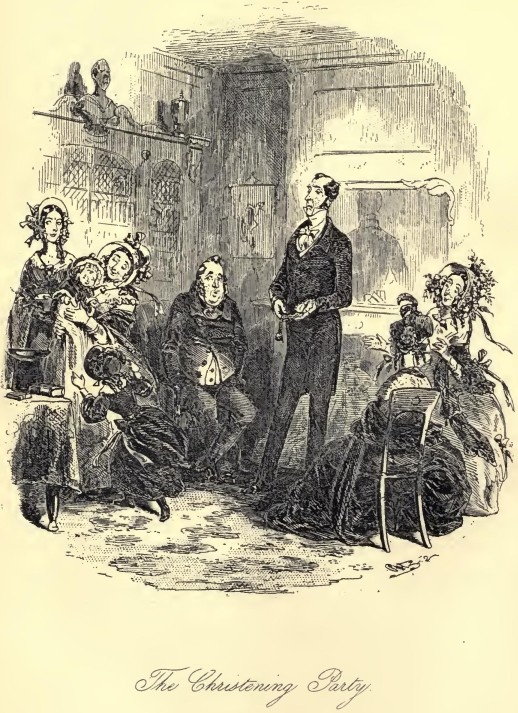

The baby soon appeared, carried in great glory by Richards; while Florence, in custody of that active young constable, Susan Nipper, brought up the rear. Though the whole nursery party were dressed by this time in lighter mourning than at first, there was enough in the appearance of the bereaved children to make the day no brighter. The baby too—it might have been Miss Tox’s nose—began to cry. Thereby, as it happened, preventing Mr Chick from the awkward fulfilment of a very honest purpose he had; which was, to make much of Florence. For this gentleman, insensible to the superior claims of a perfect Dombey (perhaps on account of having the honour to be united to a Dombey himself, and being familiar with excellence), really liked her, and showed that he liked her, and was about to show it in his own way now, when Paul cried, and his helpmate stopped him short—

“Now Florence, child!” said her aunt, briskly, “what are you doing, love? Show yourself to him. Engage his attention, my dear!”

The atmosphere became or might have become colder and colder, when Mr Dombey stood frigidly watching his little daughter, who, clapping her hands, and standing on tip-toe before the throne of his son and heir, lured him to bend down from his high estate, and look at her. Some honest act of Richards’s may have aided the effect, but he did look down, and held his peace. As his sister hid behind her nurse, he followed her with his eyes; and when she peeped out with a merry cry to him, he sprang up and crowed lustily—laughing outright when she ran in upon him; and seeming to fondle her curls with his tiny hands, while she smothered him with kisses.

Was Mr Dombey pleased to see this? He testified no pleasure by the relaxation of a nerve; but outward tokens of any kind of feeling were unusual with him. If any sunbeam stole into the room to light the children at their play, it never reached his face. He looked on so fixedly and coldly, that the warm light vanished even from the laughing eyes of little Florence, when, at last, they happened to meet his.

It was a dull, grey, autumn day indeed, and in a minute’s pause and silence that took place, the leaves fell sorrowfully.

“Mr John,” said Mr Dombey, referring to his watch, and assuming his hat and gloves. “Take my sister, if you please: my arm today is Miss Tox’s. You had better go first with Master Paul, Richards. Be very careful.”

In Mr Dombey’s carriage, Dombey and Son, Miss Tox, Mrs Chick, Richards, and Florence. In a little carriage following it, Susan Nipper and the owner Mr Chick. Susan looking out of window, without intermission, as a relief from the embarrassment of confronting the large face of that gentleman, and thinking whenever anything rattled that he was putting up in paper an appropriate pecuniary compliment for herself.

Once upon the road to church, Mr Dombey clapped his hands for the amusement of his son. At which instance of parental enthusiasm Miss Tox was enchanted. But exclusive of this incident, the chief difference between the christening party and a party in a mourning coach consisted in the colours of the carriage and horses.

Arrived at the church steps, they were received by a portentous beadle. Mr Dombey dismounting first to help the ladies out, and standing near him at the church door, looked like another beadle. A beadle less gorgeous but more dreadful; the beadle of private life; the beadle of our business and our bosoms.

Miss Tox’s hand trembled as she slipped it through Mr Dombey’s arm, and felt herself escorted up the steps, preceded by a cocked hat and a Babylonian collar. It seemed for a moment like that other solemn institution, “Wilt thou have this man, Lucretia?” “Yes, I will.”

“Please to bring the child in quick out of the air there,” whispered the beadle, holding open the inner door of the church.

Little Paul might have asked with Hamlet “into my grave?” so chill and earthy was the place. The tall, shrouded pulpit and reading desk; the dreary perspective of empty pews stretching away under the galleries, and empty benches mounting to the roof and lost in the shadow of the great grim organ; the dusty matting and cold stone slabs; the grisly free seats in the aisles; and the damp corner by the bell-rope, where the black trestles used for funerals were stowed away, along with some shovels and baskets, and a coil or two of deadly-looking rope; the strange, unusual, uncomfortable smell, and the cadaverous light; were all in unison. It was a cold and dismal scene.

“There’s a wedding just on, Sir,” said the beadle, “but it’ll be over directly, if you’ll walk into the westry here.”

Before he turned again to lead the way, he gave Mr Dombey a bow and a half smile of recognition, importing that he (the beadle) remembered to have had the pleasure of attending on him when he buried his wife, and hoped he had enjoyed himself since.

The very wedding looked dismal as they passed in front of the altar. The bride was too old and the bridegroom too young, and a superannuated beau with one eye and an eyeglass stuck in its blank companion, was giving away the lady, while the friends were shivering. In the vestry the fire was smoking; and an over-aged and over-worked and under-paid attorney’s clerk, “making a search,” was running his forefinger down the parchment pages of an immense register (one of a long series of similar volumes) gorged with burials. Over the fireplace was a ground-plan of the vaults underneath the church; and Mr Chick, skimming the literary portion of it aloud, by way of enlivening the company, read the reference to Mrs Dombey’s tomb in full, before he could stop himself.

After another cold interval, a wheezy little pew-opener afflicted with an asthma, appropriate to the churchyard, if not to the church, summoned them to the font—a rigid marble basin which seemed to have been playing a churchyard game at cup and ball with its matter of fact pedestal, and to have been just that moment caught on the top of it. Here they waited some little time while the marriage party enrolled themselves; and meanwhile the wheezy little pew-opener—partly in consequence of her infirmity, and partly that the marriage party might not forget her—went about the building coughing like a grampus.

Presently the clerk (the only cheerful-looking object there, and he was an undertaker) came up with a jug of warm water, and said something, as he poured it into the font, about taking the chill off; which millions of gallons boiling hot could not have done for the occasion. Then the clergyman, an amiable and mild-looking young curate, but obviously afraid of the baby, appeared like the principal character in a ghost-story, “a tall figure all in white;” at sight of whom Paul rent the air with his cries, and never left off again till he was taken out black in the face.

Even when that event had happened, to the great relief of everybody, he was heard under the portico, during the rest of the ceremony, now fainter, now louder, now hushed, now bursting forth again with an irrepressible sense of his wrongs. This so distracted the attention of the two ladies, that Mrs Chick was constantly deploying into the centre aisle, to send out messages by the pew-opener, while Miss Tox kept her Prayer-book open at the Gunpowder Plot, and occasionally read responses from that service.

During the whole of these proceedings, Mr Dombey remained as impassive and gentlemanly as ever, and perhaps assisted in making it so cold, that the young curate smoked at the mouth as he read. The only time that he unbent his visage in the least, was when the clergyman, in delivering (very unaffectedly and simply) the closing exhortation, relative to the future examination of the child by the sponsors, happened to rest his eye on Mr Chick; and then Mr Dombey might have been seen to express by a majestic look, that he would like to catch him at it.

It might have been well for Mr Dombey, if he had thought of his own dignity a little less; and had thought of the great origin and purpose of the ceremony in which he took so formal and so stiff a part, a little more. His arrogance contrasted strangely with its history.

When it was all over, he again gave his arm to Miss Tox, and conducted her to the vestry, where he informed the clergyman how much pleasure it would have given him to have solicited the honour of his company at dinner, but for the unfortunate state of his household affairs. The register signed, and the fees paid, and the pew-opener (whose cough was very bad again) remembered, and the beadle gratified, and the sexton (who was accidentally on the doorsteps, looking with great interest at the weather) not forgotten, they got into the carriage again, and drove home in the same bleak fellowship.

There they found Mr Pitt turning up his nose at a cold collation, set forth in a cold pomp of glass and silver, and looking more like a dead dinner lying in state than a social refreshment. On their arrival Miss Tox produced a mug for her godson, and Mr Chick a knife and fork and spoon in a case. Mr Dombey also produced a bracelet for Miss Tox; and, on the receipt of this token, Miss Tox was tenderly affected.

“Mr John,” said Mr Dombey, “will you take the bottom of the table, if you please? What have you got there, Mr John?”

“I have got a cold fillet of veal here, Sir,” replied Mr Chick, rubbing his numbed hands hard together. “What have you got there, Sir?”

“This,” returned Mr Dombey, “is some cold preparation of calf’s head, I think. I see cold fowls—ham—patties—salad—lobster. Miss Tox will do me the honour of taking some wine? Champagne to Miss Tox.”

There was a toothache in everything. The wine was so bitter cold that it forced a little scream from Miss Tox, which she had great difficulty in turning into a “Hem!” The veal had come from such an airy pantry, that the first taste of it had struck a sensation as of cold lead to Mr Chick’s extremities. Mr Dombey alone remained unmoved. He might have been hung up for sale at a Russian fair as a specimen of a frozen gentleman.

The prevailing influence was too much even for his sister. She made no effort at flattery or small talk, and directed all her efforts to looking as warm as she could.

“Well, Sir,” said Mr Chick, making a desperate plunge, after a long silence, and filling a glass of sherry; “I shall drink this, if you’ll allow me, Sir, to little Paul.”

“Bless him!” murmured Miss Tox, taking a sip of wine.

“Dear little Dombey!” murmured Mrs Chick.

“Mr John,” said Mr Dombey, with severe gravity, “my son would feel and express himself obliged to you, I have no doubt, if he could appreciate the favour you have done him. He will prove, in time to come, I trust, equal to any responsibility that the obliging disposition of his relations and friends, in private, or the onerous nature of our position, in public, may impose upon him.”

The tone in which this was said admitting of nothing more, Mr Chick relapsed into low spirits and silence. Not so Miss Tox, who, having listened to Mr Dombey with even a more emphatic attention than usual, and with a more expressive tendency of her head to one side, now leant across the table, and said to Mrs Chick softly:

“Louisa!”

“My dear,” said Mrs Chick.

“Onerous nature of our position in public may—I have forgotten the exact term.”

“Expose him to,” said Mrs Chick.

“Pardon me, my dear,” returned Miss Tox, “I think not. It was more rounded and flowing. Obliging disposition of relations and friends in private, or onerous nature of position in public—may—impose upon him!”

“Impose upon him, to be sure,” said Mrs Chick.

Miss Tox struck her delicate hands together lightly, in triumph; and added, casting up her eyes, “eloquence indeed!”

Mr Dombey, in the meanwhile, had issued orders for the attendance of Richards, who now entered curtseying, but without the baby; Paul being asleep after the fatigues of the morning. Mr Dombey, having delivered a glass of wine to this vassal, addressed her in the following words: Miss Tox previously settling her head on one side, and making other little arrangements for engraving them on her heart.

“During the six months or so, Richards, which have seen you an inmate of this house, you have done your duty. Desiring to connect some little service to you with this occasion, I considered how I could best effect that object, and I also advised with my sister, Mrs—”

“Chick,” interposed the gentleman of that name.

“Oh, hush if you please!” said Miss Tox.

“I was about to say to you, Richards,” resumed Mr Dombey, with an appalling glance at Mr John, “that I was further assisted in my decision, by the recollection of a conversation I held with your husband in this room, on the occasion of your being hired, when he disclosed to me the melancholy fact that your family, himself at the head, were sunk and steeped in ignorance.”

Richards quailed under the magnificence of the reproof.

“I am far from being friendly,” pursued Mr Dombey, “to what is called by persons of levelling sentiments, general education. But it is necessary that the inferior classes should continue to be taught to know their position, and to conduct themselves properly. So far I approve of schools. Having the power of nominating a child on the foundation of an ancient establishment, called (from a worshipful company) the Charitable Grinders; where not only is a wholesome education bestowed upon the scholars, but where a dress and badge is likewise provided for them; I have (first communicating, through Mrs Chick, with your family) nominated your eldest son to an existing vacancy; and he has this day, I am informed, assumed the habit. The number of her son, I believe,” said Mr Dombey, turning to his sister and speaking of the child as if he were a hackney-coach, is one hundred and forty-seven. Louisa, you can tell her.”

“One hundred and forty-seven,” said Mrs Chick “The dress, Richards, is a nice, warm, blue baize tailed coat and cap, turned up with orange coloured binding; red worsted stockings; and very strong leather small-clothes. One might wear the articles one’s self,” said Mrs Chick, with enthusiasm, “and be grateful.”

“There, Richards!” said Miss Tox. “Now, indeed, you may be proud. The Charitable Grinders!”

“I am sure I am very much obliged, Sir,” returned Richards faintly, “and take it very kind that you should remember my little ones.” At the same time a vision of Biler as a Charitable Grinder, with his very small legs encased in the serviceable clothing described by Mrs Chick, swam before Richards’s eyes, and made them water.

“I am very glad to see you have so much feeling, Richards,” said Miss Tox.

“It makes one almost hope, it really does,” said Mrs Chick, who prided herself on taking trustful views of human nature, “that there may yet be some faint spark of gratitude and right feeling in the world.”

Richards deferred to these compliments by curtseying and murmuring her thanks; but finding it quite impossible to recover her spirits from the disorder into which they had been thrown by the image of her son in his precocious nether garments, she gradually approached the door and was heartily relieved to escape by it.

Such temporary indications of a partial thaw that had appeared with her, vanished with her; and the frost set in again, as cold and hard as ever. Mr Chick was twice heard to hum a tune at the bottom of the table, but on both occasions it was a fragment of the Dead March in Saul. The party seemed to get colder and colder, and to be gradually resolving itself into a congealed and solid state, like the collation round which it was assembled. At length Mrs Chick looked at Miss Tox, and Miss Tox returned the look, and they both rose and said it was really time to go. Mr Dombey receiving this announcement with perfect equanimity, they took leave of that gentleman, and presently departed under the protection of Mr Chick; who, when they had turned their backs upon the house and left its master in his usual solitary state, put his hands in his pockets, threw himself back in the carriage, and whistled “With a hey ho chevy!” all through; conveying into his face as he did so, an expression of such gloomy and terrible defiance, that Mrs Chick dared not protest, or in any way molest him.

Richards, though she had little Paul on her lap, could not forget her own first-born. She felt it was ungrateful; but the influence of the day fell even on the Charitable Grinders, and she could hardly help regarding his pewter badge, number one hundred and forty-seven, as, somehow, a part of its formality and sternness. She spoke, too, in the nursery, of his “blessed legs,” and was again troubled by his spectre in uniform.

“I don’t know what I wouldn’t give,” said Polly, “to see the poor little dear before he gets used to ’em.”

“Why, then, I tell you what, Mrs Richards,” retorted Nipper, who had been admitted to her confidence, “see him and make your mind easy.”

“Mr Dombey wouldn’t like it,” said Polly.

“Oh, wouldn’t he, Mrs Richards!” retorted Nipper, “he’d like it very much, I think when he was asked.”

“You wouldn’t ask him, I suppose, at all?” said Polly.

“No, Mrs Richards, quite contrairy,” returned Susan, “and them two inspectors Tox and Chick, not intending to be on duty tomorrow, as I heard ’em say, me and Miss Floy will go along with you tomorrow morning, and welcome, Mrs Richards, if you like, for we may as well walk there as up and down a street, and better too.”

Polly rejected the idea pretty stoutly at first; but by little and little she began to entertain it, as she entertained more and more distinctly the forbidden pictures of her children, and her own home. At length, arguing that there could be no great harm in calling for a moment at the door, she yielded to the Nipper proposition.

The matter being settled thus, little Paul began to cry most piteously, as if he had a foreboding that no good would come of it.

“What’s the matter with the child?” asked Susan.

“He’s cold, I think,” said Polly, walking with him to and fro, and hushing him.

It was a bleak autumnal afternoon indeed; and as she walked, and hushed, and, glancing through the dreary windows, pressed the little fellow closer to her breast, the withered leaves came showering down.