‘As we gang awa’ fra’ Lunnun tomorrow neeght, and as I dinnot know that I was e’er so happy in a’ my days, Misther Nickleby, Ding! but I will tak’ anoother glass to our next merry meeting!’

So said John Browdie, rubbing his hands with great joyousness, and looking round him with a ruddy shining face, quite in keeping with the declaration.

The time at which John found himself in this enviable condition was the same evening to which the last chapter bore reference; the place was the cottage; and the assembled company were Nicholas, Mrs. Nickleby, Mrs Browdie, Kate Nickleby, and Smike.

A very merry party they had been. Mrs. Nickleby, knowing of her son’s obligations to the honest Yorkshireman, had, after some demur, yielded her consent to Mr. and Mrs. Browdie being invited out to tea; in the way of which arrangement, there were at first sundry difficulties and obstacles, arising out of her not having had an opportunity of ‘calling’ upon Mrs Browdie first; for although Mrs. Nickleby very often observed with much complacency (as most punctilious people do), that she had not an atom of pride or formality about her, still she was a great stickler for dignity and ceremonies; and as it was manifest that, until a call had been made, she could not be (politely speaking, and according to the laws of society) even cognisant of the fact of Mrs. Browdie’s existence, she felt her situation to be one of peculiar delicacy and difficulty.

‘The call must originate with me, my dear,’ said Mrs. Nickleby, ‘that’s indispensable. The fact is, my dear, that it’s necessary there should be a sort of condescension on my part, and that I should show this young person that I am willing to take notice of her. There’s a very respectable-looking young man,’ added Mrs. Nickleby, after a short consideration, ‘who is conductor to one of the omnibuses that go by here, and who wears a glazed hat—your sister and I have noticed him very often—he has a wart upon his nose, Kate, you know, exactly like a gentleman’s servant.’

‘Have all gentlemen’s servants warts upon their noses, mother?’ asked Nicholas.

‘Nicholas, my dear, how very absurd you are,’ returned his mother; ‘of course I mean that his glazed hat looks like a gentleman’s servant, and not the wart upon his nose; though even that is not so ridiculous as it may seem to you, for we had a footboy once, who had not only a wart, but a wen also, and a very large wen too, and he demanded to have his wages raised in consequence, because he found it came very expensive. Let me see, what was I—oh yes, I know. The best way that I can think of would be to send a card, and my compliments, (I’ve no doubt he’d take ‘em for a pot of porter,) by this young man, to the Saracen with Two Necks. If the waiter took him for a gentleman’s servant, so much the better. Then all Mrs. Browdie would have to do would be to send her card back by the carrier (he could easily come with a double knock), and there’s an end of it.’

‘My dear mother,’ said Nicholas, ‘I don’t suppose such unsophisticated people as these ever had a card of their own, or ever will have.’

‘Oh that, indeed, Nicholas, my dear,’ returned Mrs. Nickleby, ‘that’s another thing. If you put it upon that ground, why, of course, I have no more to say, than that I have no doubt they are very good sort of persons, and that I have no kind of objection to their coming here to tea if they like, and shall make a point of being very civil to them if they do.’

The point being thus effectually set at rest, and Mrs. Nickleby duly placed in the patronising and mildly-condescending position which became her rank and matrimonial years, Mr. and Mrs. Browdie were invited and came; and as they were very deferential to Mrs. Nickleby, and seemed to have a becoming appreciation of her greatness, and were very much pleased with everything, the good lady had more than once given Kate to understand, in a whisper, that she thought they were the very best-meaning people she had ever seen, and perfectly well behaved.

And thus it came to pass, that John Browdie declared, in the parlour after supper, to wit, and twenty minutes before eleven o’clock p.m., that he had never been so happy in all his days.

Nor was Mrs. Browdie much behind her husband in this respect, for that young matron, whose rustic beauty contrasted very prettily with the more delicate loveliness of Kate, and without suffering by the contrast either, for each served as it were to set off and decorate the other, could not sufficiently admire the gentle and winning manners of the young lady, or the engaging affability of the elder one. Then Kate had the art of turning the conversation to subjects upon which the country girl, bashful at first in strange company, could feel herself at home; and if Mrs. Nickleby was not quite so felicitous at times in the selection of topics of discourse, or if she did seem, as Mrs. Browdie expressed it, ‘rather high in her notions,’ still nothing could be kinder, and that she took considerable interest in the young couple was manifest from the very long lectures on housewifery with which she was so obliging as to entertain Mrs. Browdie’s private ear, which were illustrated by various references to the domestic economy of the cottage, in which (those duties falling exclusively upon Kate) the good lady had about as much share, either in theory or practice, as any one of the statues of the Twelve Apostles which embellish the exterior of St Paul’s Cathedral.

‘Mr. Browdie,’ said Kate, addressing his young wife, ‘is the best-humoured, the kindest and heartiest creature I ever saw. If I were oppressed with I don’t know how many cares, it would make me happy only to look at him.’

‘He does seem indeed, upon my word, a most excellent creature, Kate,’ said Mrs. Nickleby; ‘most excellent. And I am sure that at all times it will give me pleasure—really pleasure now—to have you, Mrs. Browdie, to see me in this plain and homely manner. We make no display,’ said Mrs Nickleby, with an air which seemed to insinuate that they could make a vast deal if they were so disposed; ‘no fuss, no preparation; I wouldn’t allow it. I said, “Kate, my dear, you will only make Mrs. Browdie feel uncomfortable, and how very foolish and inconsiderate that would be!”’

‘I am very much obliged to you, I am sure, ma’am,’ returned Mrs. Browdie, gratefully. ‘It’s nearly eleven o’clock, John. I am afraid we are keeping you up very late, ma’am.’

‘Late!’ cried Mrs. Nickleby, with a sharp thin laugh, and one little cough at the end, like a note of admiration expressed. ‘This is quite early for us. We used to keep such hours! Twelve, one, two, three o’clock was nothing to us. Balls, dinners, card-parties! Never were such rakes as the people about where we used to live. I often think now, I am sure, that how we ever could go through with it is quite astonishing, and that is just the evil of having a large connection and being a great deal sought after, which I would recommend all young married people steadily to resist; though of course, and it’s perfectly clear, and a very happy thing too, I think, that very few young married people can be exposed to such temptations. There was one family in particular, that used to live about a mile from us—not straight down the road, but turning sharp off to the left by the turnpike where the Plymouth mail ran over the donkey—that were quite extraordinary people for giving the most extravagant parties, with artificial flowers and champagne, and variegated lamps, and, in short, every delicacy of eating and drinking that the most singular epicure could possibly require. I don’t think that there ever were such people as those Peltiroguses. You remember the Peltiroguses, Kate?’

Kate saw that for the ease and comfort of the visitors it was high time to stay this flood of recollection, so answered that she entertained of the Peltiroguses a most vivid and distinct remembrance; and then said that Mr Browdie had half promised, early in the evening, that he would sing a Yorkshire song, and that she was most impatient that he should redeem his promise, because she was sure it would afford her mama more amusement and pleasure than it was possible to express.

Mrs. Nickleby confirming her daughter with the best possible grace—for there was patronage in that too, and a kind of implication that she had a discerning taste in such matters, and was something of a critic—John Browdie proceeded to consider the words of some north-country ditty, and to take his wife’s recollection respecting the same. This done, he made divers ungainly movements in his chair, and singling out one particular fly on the ceiling from the other flies there asleep, fixed his eyes upon him, and began to roar a meek sentiment (supposed to be uttered by a gentle swain fast pining away with love and despair) in a voice of thunder.

At the end of the first verse, as though some person without had waited until then to make himself audible, was heard a loud and violent knocking at the street-door; so loud and so violent, indeed, that the ladies started as by one accord, and John Browdie stopped.

‘It must be some mistake,’ said Nicholas, carelessly. ‘We know nobody who would come here at this hour.’

Mrs. Nickleby surmised, however, that perhaps the counting-house was burnt down, or perhaps ‘the Mr. Cheerybles’ had sent to take Nicholas into partnership (which certainly appeared highly probable at that time of night), or perhaps Mr. Linkinwater had run away with the property, or perhaps Miss La Creevy was taken in, or perhaps—

But a hasty exclamation from Kate stopped her abruptly in her conjectures, and Ralph Nickleby walked into the room.

‘Stay,’ said Ralph, as Nicholas rose, and Kate, making her way towards him, threw herself upon his arm. ‘Before that boy says a word, hear me.’

Nicholas bit his lip and shook his head in a threatening manner, but appeared for the moment unable to articulate a syllable. Kate clung closer to his arm, Smike retreated behind them, and John Browdie, who had heard of Ralph, and appeared to have no great difficulty in recognising him, stepped between the old man and his young friend, as if with the intention of preventing either of them from advancing a step further.

‘Hear me, I say,’ said Ralph, ‘and not him.’

‘Say what thou’st gotten to say then, sir,’ retorted John; ‘and tak’ care thou dinnot put up angry bluid which thou’dst betther try to quiet.’

‘I should know you,’ said Ralph, ‘by your tongue; and him’ (pointing to Smike) ‘by his looks.’

‘Don’t speak to him,’ said Nicholas, recovering his voice. ‘I will not have it. I will not hear him. I do not know that man. I cannot breathe the air that he corrupts. His presence is an insult to my sister. It is shame to see him. I will not bear it.’

‘Stand!’ cried John, laying his heavy hand upon his chest.

‘Then let him instantly retire,’ said Nicholas, struggling. ‘I am not going to lay hands upon him, but he shall withdraw. I will not have him here. John, John Browdie, is this my house, am I a child? If he stands there,’ cried Nicholas, burning with fury, ‘looking so calmly upon those who know his black and dastardly heart, he’ll drive me mad.’

To all these exclamations John Browdie answered not a word, but he retained his hold upon Nicholas; and when he was silent again, spoke.

‘There’s more to say and hear than thou think’st for,’ said John. ‘I tell’ee I ha’ gotten scent o’ thot already. Wa’at be that shadow ootside door there? Noo, schoolmeasther, show thyself, mun; dinnot be sheame-feaced. Noo, auld gen’l’man, let’s have schoolmeasther, coom.’

Hearing this adjuration, Mr. Squeers, who had been lingering in the passage until such time as it should be expedient for him to enter and he could appear with effect, was fain to present himself in a somewhat undignified and sneaking way; at which John Browdie laughed with such keen and heartfelt delight, that even Kate, in all the pain, anxiety, and surprise of the scene, and though the tears were in her eyes, felt a disposition to join him.

‘Have you done enjoying yourself, sir?’ said Ralph, at length.

‘Pratty nigh for the prasant time, sir,’ replied John.

‘I can wait,’ said Ralph. ‘Take your own time, pray.’

Ralph waited until there was a perfect silence, and then turning to Mrs Nickleby, but directing an eager glance at Kate, as if more anxious to watch his effect upon her, said:

‘Now, ma’am, listen to me. I don’t imagine that you were a party to a very fine tirade of words sent me by that boy of yours, because I don’t believe that under his control, you have the slightest will of your own, or that your advice, your opinion, your wants, your wishes, anything which in nature and reason (or of what use is your great experience?) ought to weigh with him, has the slightest influence or weight whatever, or is taken for a moment into account.’

Mrs. Nickleby shook her head and sighed, as if there were a good deal in that, certainly.

‘For this reason,’ resumed Ralph, ‘I address myself to you, ma’am. For this reason, partly, and partly because I do not wish to be disgraced by the acts of a vicious stripling whom I was obliged to disown, and who, afterwards, in his boyish majesty, feigns to—ha! ha!—to disown me, I present myself here tonight. I have another motive in coming: a motive of humanity. I come here,’ said Ralph, looking round with a biting and triumphant smile, and gloating and dwelling upon the words as if he were loath to lose the pleasure of saying them, ‘to restore a parent his child. Ay, sir,’ he continued, bending eagerly forward, and addressing Nicholas, as he marked the change of his countenance, ‘to restore a parent his child; his son, sir; trepanned, waylaid, and guarded at every turn by you, with the base design of robbing him some day of any little wretched pittance of which he might become possessed.’

‘In that, you know you lie,’ said Nicholas, proudly.

‘In this, I know I speak the truth. I have his father here,’ retorted Ralph.

‘Here!’ sneered Squeers, stepping forward. ‘Do you hear that? Here! Didn’t I tell you to be careful that his father didn’t turn up and send him back to me? Why, his father’s my friend; he’s to come back to me directly, he is. Now, what do you say—eh!—now—come—what do you say to that—an’t you sorry you took so much trouble for nothing? an’t you? an’t you?’

‘You bear upon your body certain marks I gave you,’ said Nicholas, looking quietly away, ‘and may talk in acknowledgment of them as much as you please. You’ll talk a long time before you rub them out, Mr. Squeers.’

The estimable gentleman last named cast a hasty look at the table, as if he were prompted by this retort to throw a jug or bottle at the head of Nicholas, but he was interrupted in this design (if such design he had) by Ralph, who, touching him on the elbow, bade him tell the father that he might now appear and claim his son.

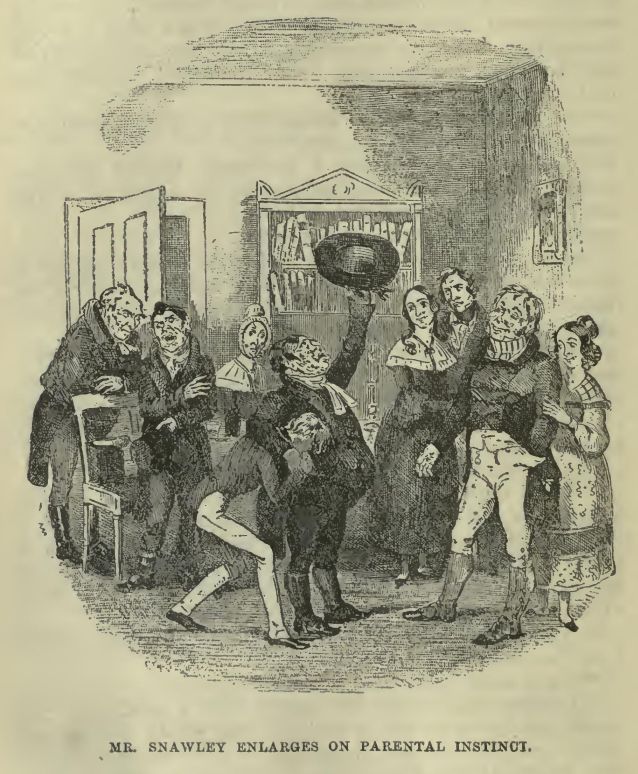

This being purely a labour of love, Mr. Squeers readily complied, and leaving the room for the purpose, almost immediately returned, supporting a sleek personage with an oily face, who, bursting from him, and giving to view the form and face of Mr. Snawley, made straight up to Smike, and tucking that poor fellow’s head under his arm in a most uncouth and awkward embrace, elevated his broad-brimmed hat at arm’s length in the air as a token of devout thanksgiving, exclaiming, meanwhile, ‘How little did I think of this here joyful meeting, when I saw him last! Oh, how little did I think it!’

‘Be composed, sir,’ said Ralph, with a gruff expression of sympathy, ‘you have got him now.’

‘Got him! Oh, haven’t I got him! Have I got him, though?’ cried Mr Snawley, scarcely able to believe it. ‘Yes, here he is, flesh and blood, flesh and blood.’

‘Vary little flesh,’ said John Browdie.

Mr. Snawley was too much occupied by his parental feelings to notice this remark; and, to assure himself more completely of the restoration of his child, tucked his head under his arm again, and kept it there.

‘What was it,’ said Snawley, ‘that made me take such a strong interest in him, when that worthy instructor of youth brought him to my house? What was it that made me burn all over with a wish to chastise him severely for cutting away from his best friends, his pastors and masters?’

‘It was parental instinct, sir,’ observed Squeers.

‘That’s what it was, sir,’ rejoined Snawley; ‘the elevated feeling, the feeling of the ancient Romans and Grecians, and of the beasts of the field and birds of the air, with the exception of rabbits and tom-cats, which sometimes devour their offspring. My heart yearned towards him. I could have—I don’t know what I couldn’t have done to him in the anger of a father.’

‘It only shows what Natur is, sir,’ said Mr. Squeers. ‘She’s rum ‘un, is Natur.’

‘She is a holy thing, sir,’ remarked Snawley.

‘I believe you,’ added Mr. Squeers, with a moral sigh. ‘I should like to know how we should ever get on without her. Natur,’ said Mr. Squeers, solemnly, ‘is more easier conceived than described. Oh what a blessed thing, sir, to be in a state of natur!’

Pending this philosophical discourse, the bystanders had been quite stupefied with amazement, while Nicholas had looked keenly from Snawley to Squeers, and from Squeers to Ralph, divided between his feelings of disgust, doubt, and surprise. At this juncture, Smike escaping from his father fled to Nicholas, and implored him, in most moving terms, never to give him up, but to let him live and die beside him.

‘If you are this boy’s father,’ said Nicholas, ‘look at the wreck he is, and tell me that you purpose to send him back to that loathsome den from which I brought him.’

‘Scandal again!’ cried Squeers. ‘Recollect, you an’t worth powder and shot, but I’ll be even with you one way or another.’

‘Stop,’ interposed Ralph, as Snawley was about to speak. ‘Let us cut this matter short, and not bandy words here with hare-brained profligates. This is your son, as you can prove. And you, Mr. Squeers, you know this boy to be the same that was with you for so many years under the name of Smike. Do you?’

‘Do I!’ returned Squeers. ‘Don’t I?’

‘Good,’ said Ralph; ‘a very few words will be sufficient here. You had a son by your first wife, Mr. Snawley?’

‘I had,’ replied that person, ‘and there he stands.’

‘We’ll show that presently,’ said Ralph. ‘You and your wife were separated, and she had the boy to live with her, when he was a year old. You received a communication from her, when you had lived apart a year or two, that the boy was dead; and you believed it?’

‘Of course I did!’ returned Snawley. ‘Oh the joy of—’

‘Be rational, sir, pray,’ said Ralph. ‘This is business, and transports interfere with it. This wife died a year and a half ago, or thereabouts—not more—in some obscure place, where she was housekeeper in a family. Is that the case?’

‘That’s the case,’ replied Snawley.

‘Having written on her death-bed a letter or confession to you, about this very boy, which, as it was not directed otherwise than in your name, only reached you, and that by a circuitous course, a few days since?’

‘Just so,’ said Snawley. ‘Correct in every particular, sir.’

‘And this confession,’ resumed Ralph, ‘is to the effect that his death was an invention of hers to wound you—was a part of a system of annoyance, in short, which you seem to have adopted towards each other—that the boy lived, but was of weak and imperfect intellect—that she sent him by a trusty hand to a cheap school in Yorkshire—that she had paid for his education for some years, and then, being poor, and going a long way off, gradually deserted him, for which she prayed forgiveness?’

Snawley nodded his head, and wiped his eyes; the first slightly, the last violently.

‘The school was Mr. Squeers’s,’ continued Ralph; ‘the boy was left there in the name of Smike; every description was fully given, dates tally exactly with Mr. Squeers’s books, Mr. Squeers is lodging with you at this time; you have two other boys at his school: you communicated the whole discovery to him, he brought you to me as the person who had recommended to him the kidnapper of his child; and I brought you here. Is that so?’

‘You talk like a good book, sir, that’s got nothing in its inside but what’s the truth,’ replied Snawley.

‘This is your pocket-book,’ said Ralph, producing one from his coat; ‘the certificates of your first marriage and of the boy’s birth, and your wife’s two letters, and every other paper that can support these statements directly or by implication, are here, are they?’

‘Every one of ‘em, sir.’

‘And you don’t object to their being looked at here, so that these people may be convinced of your power to substantiate your claim at once in law and reason, and you may resume your control over your own son without more delay. Do I understand you?’

‘I couldn’t have understood myself better, sir.’

‘There, then,’ said Ralph, tossing the pocket-book upon the table. ‘Let them see them if they like; and as those are the original papers, I should recommend you to stand near while they are being examined, or you may chance to lose some.’

With these words Ralph sat down unbidden, and compressing his lips, which were for the moment slightly parted by a smile, folded his arms, and looked for the first time at his nephew.

Nicholas, stung by the concluding taunt, darted an indignant glance at him; but commanding himself as well as he could, entered upon a close examination of the documents, at which John Browdie assisted. There was nothing about them which could be called in question. The certificates were regularly signed as extracts from the parish books, the first letter had a genuine appearance of having been written and preserved for some years, the handwriting of the second tallied with it exactly, (making proper allowance for its having been written by a person in extremity,) and there were several other corroboratory scraps of entries and memoranda which it was equally difficult to question.

‘Dear Nicholas,’ whispered Kate, who had been looking anxiously over his shoulder, ‘can this be really the case? Is this statement true?’

‘I fear it is,’ answered Nicholas. ‘What say you, John?’

John scratched his head and shook it, but said nothing at all.

‘You will observe, ma’am,’ said Ralph, addressing himself to Mrs. Nickleby, ‘that this boy being a minor and not of strong mind, we might have come here tonight, armed with the powers of the law, and backed by a troop of its myrmidons. I should have done so, ma’am, unquestionably, but for my regard for the feelings of yourself, and your daughter.’

‘You have shown your regard for her feelings well,’ said Nicholas, drawing his sister towards him.

‘Thank you,’ replied Ralph. ‘Your praise, sir, is commendation, indeed.’

‘Well,’ said Squeers, ‘what’s to be done? Them hackney-coach horses will catch cold if we don’t think of moving; there’s one of ‘em a sneezing now, so that he blows the street door right open. What’s the order of the day? Is Master Snawley to come along with us?’

‘No, no, no,’ replied Smike, drawing back, and clinging to Nicholas.

‘No. Pray, no. I will not go from you with him. No, no.’

‘This is a cruel thing,’ said Snawley, looking to his friends for support. ‘Do parents bring children into the world for this?’

‘Do parents bring children into the world for thot?’ said John Browdie bluntly, pointing, as he spoke, to Squeers.

‘Never you mind,’ retorted that gentleman, tapping his nose derisively.

‘Never I mind!’ said John, ‘no, nor never nobody mind, say’st thou, schoolmeasther. It’s nobody’s minding that keeps sike men as thou afloat. Noo then, where be’est thou coomin’ to? Dang it, dinnot coom treadin’ ower me, mun.’

Suiting the action to the word, John Browdie just jerked his elbow into the chest of Mr. Squeers who was advancing upon Smike; with so much dexterity that the schoolmaster reeled and staggered back upon Ralph Nickleby, and being unable to recover his balance, knocked that gentleman off his chair, and stumbled heavily upon him.

This accidental circumstance was the signal for some very decisive proceedings. In the midst of a great noise, occasioned by the prayers and entreaties of Smike, the cries and exclamations of the women, and the vehemence of the men, demonstrations were made of carrying off the lost son by violence. Squeers had actually begun to haul him out, when Nicholas (who, until then, had been evidently undecided how to act) took him by the collar, and shaking him so that such teeth as he had, chattered in his head, politely escorted him to the room-door, and thrusting him into the passage, shut it upon him.

‘Now,’ said Nicholas to the other two, ‘have the goodness to follow your friend.’

‘I want my son,’ said Snawley.

‘Your son,’ replied Nicholas, ‘chooses for himself. He chooses to remain here, and he shall.’

‘You won’t give him up?’ said Snawley.

‘I would not give him up against his will, to be the victim of such brutality as that to which you would consign him,’ replied Nicholas, ‘if he were a dog or a rat.’

‘Knock that Nickleby down with a candlestick,’ cried Mr. Squeers, through the keyhole, ‘and bring out my hat, somebody, will you, unless he wants to steal it.’

‘I am very sorry, indeed,’ said Mrs. Nickleby, who, with Mrs. Browdie, had stood crying and biting her fingers in a corner, while Kate (very pale, but perfectly quiet) had kept as near her brother as she could. ‘I am very sorry, indeed, for all this. I really don’t know what would be best to do, and that’s the truth. Nicholas ought to be the best judge, and I hope he is. Of course, it’s a hard thing to have to keep other people’s children, though young Mr. Snawley is certainly as useful and willing as it’s possible for anybody to be; but, if it could be settled in any friendly manner—if old Mr. Snawley, for instance, would settle to pay something certain for his board and lodging, and some fair arrangement was come to, so that we undertook to have fish twice a week, and a pudding twice, or a dumpling, or something of that sort—I do think that it might be very satisfactory and pleasant for all parties.’

This compromise, which was proposed with abundance of tears and sighs, not exactly meeting the point at issue, nobody took any notice of it; and poor Mrs. Nickleby accordingly proceeded to enlighten Mrs. Browdie upon the advantages of such a scheme, and the unhappy results flowing, on all occasions, from her not being attended to when she proffered her advice.

‘You, sir,’ said Snawley, addressing the terrified Smike, ‘are an unnatural, ungrateful, unlovable boy. You won’t let me love you when I want to. Won’t you come home, won’t you?’

‘No, no, no,’ cried Smike, shrinking back.

‘He never loved nobody,’ bawled Squeers, through the keyhole. ‘He never loved me; he never loved Wackford, who is next door but one to a cherubim. How can you expect that he’ll love his father? He’ll never love his father, he won’t. He don’t know what it is to have a father. He don’t understand it. It an’t in him.’

Mr. Snawley looked steadfastly at his son for a full minute, and then covering his eyes with his hand, and once more raising his hat in the air, appeared deeply occupied in deploring his black ingratitude. Then drawing his arm across his eyes, he picked up Mr. Squeers’s hat, and taking it under one arm, and his own under the other, walked slowly and sadly out.

‘Your romance, sir,’ said Ralph, lingering for a moment, ‘is destroyed, I take it. No unknown; no persecuted descendant of a man of high degree; but the weak, imbecile son of a poor, petty tradesman. We shall see how your sympathy melts before plain matter of fact.’

‘You shall,’ said Nicholas, motioning towards the door.

‘And trust me, sir,’ added Ralph, ‘that I never supposed you would give him up tonight. Pride, obstinacy, reputation for fine feeling, were all against it. These must be brought down, sir, lowered, crushed, as they shall be soon. The protracted and wearing anxiety and expense of the law in its most oppressive form, its torture from hour to hour, its weary days and sleepless nights, with these I’ll prove you, and break your haughty spirit, strong as you deem it now. And when you make this house a hell, and visit these trials upon yonder wretched object (as you will; I know you), and those who think you now a young-fledged hero, we’ll go into old accounts between us two, and see who stands the debtor, and comes out best at last, even before the world.’

Ralph Nickleby withdrew. But Mr. Squeers, who had heard a portion of this closing address, and was by this time wound up to a pitch of impotent malignity almost unprecedented, could not refrain from returning to the parlour door, and actually cutting some dozen capers with various wry faces and hideous grimaces, expressive of his triumphant confidence in the downfall and defeat of Nicholas.

Having concluded this war-dance, in which his short trousers and large boots had borne a very conspicuous figure, Mr. Squeers followed his friends, and the family were left to meditate upon recent occurrences.