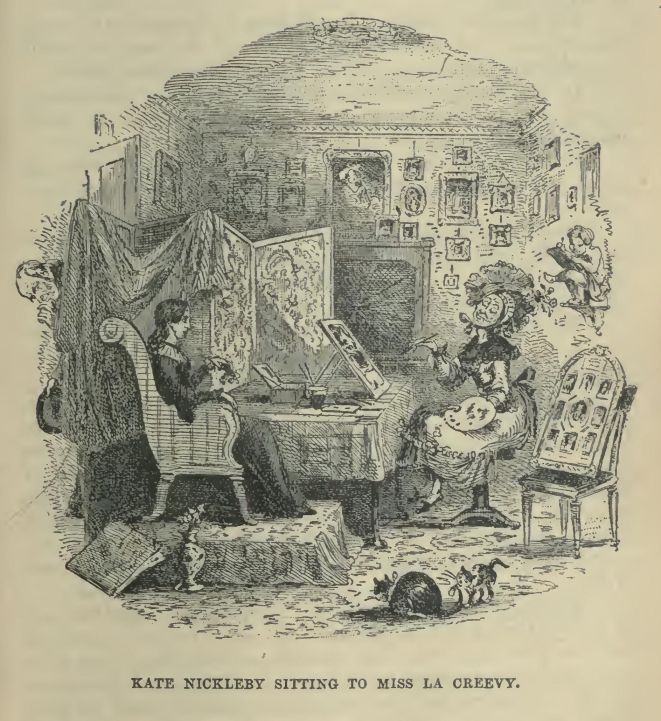

On the second morning after the departure of Nicholas for Yorkshire, Kate Nickleby sat in a very faded chair raised upon a very dusty throne in Miss La Creevy’s room, giving that lady a sitting for the portrait upon which she was engaged; and towards the full perfection of which, Miss La Creevy had had the street-door case brought upstairs, in order that she might be the better able to infuse into the counterfeit countenance of Miss Nickleby, a bright salmon flesh-tint which she had originally hit upon while executing the miniature of a young officer therein contained, and which bright salmon flesh-tint was considered, by Miss La Creevy’s chief friends and patrons, to be quite a novelty in art: as indeed it was.

‘I think I have caught it now,’ said Miss La Creevy. ‘The very shade! This will be the sweetest portrait I have ever done, certainly.’

‘It will be your genius that makes it so, then, I am sure,’ replied Kate, smiling.

‘No, no, I won’t allow that, my dear,’ rejoined Miss La Creevy. ‘It’s a very nice subject—a very nice subject, indeed—though, of course, something depends upon the mode of treatment.’

‘And not a little,’ observed Kate.

‘Why, my dear, you are right there,’ said Miss La Creevy, ‘in the main you are right there; though I don’t allow that it is of such very great importance in the present case. Ah! The difficulties of Art, my dear, are great.’

‘They must be, I have no doubt,’ said Kate, humouring her good-natured little friend.

‘They are beyond anything you can form the faintest conception of,’ replied Miss La Creevy. ‘What with bringing out eyes with all one’s power, and keeping down noses with all one’s force, and adding to heads, and taking away teeth altogether, you have no idea of the trouble one little miniature is.’

‘The remuneration can scarcely repay you,’ said Kate.

‘Why, it does not, and that’s the truth,’ answered Miss La Creevy; ‘and then people are so dissatisfied and unreasonable, that, nine times out of ten, there’s no pleasure in painting them. Sometimes they say, “Oh, how very serious you have made me look, Miss La Creevy!” and at others, “La, Miss La Creevy, how very smirking!” when the very essence of a good portrait is, that it must be either serious or smirking, or it’s no portrait at all.’

‘Indeed!’ said Kate, laughing.

‘Certainly, my dear; because the sitters are always either the one or the other,’ replied Miss La Creevy. ‘Look at the Royal Academy! All those beautiful shiny portraits of gentlemen in black velvet waistcoats, with their fists doubled up on round tables, or marble slabs, are serious, you know; and all the ladies who are playing with little parasols, or little dogs, or little children—it’s the same rule in art, only varying the objects—are smirking. In fact,’ said Miss La Creevy, sinking her voice to a confidential whisper, ‘there are only two styles of portrait painting; the serious and the smirk; and we always use the serious for professional people (except actors sometimes), and the smirk for private ladies and gentlemen who don’t care so much about looking clever.’

Kate seemed highly amused by this information, and Miss La Creevy went on painting and talking, with immovable complacency.

‘What a number of officers you seem to paint!’ said Kate, availing herself of a pause in the discourse, and glancing round the room.

‘Number of what, child?’ inquired Miss La Creevy, looking up from her work. ‘Character portraits, oh yes—they’re not real military men, you know.’

‘No!’

‘Bless your heart, of course not; only clerks and that, who hire a uniform coat to be painted in, and send it here in a carpet bag. Some artists,’ said Miss La Creevy, ‘keep a red coat, and charge seven-and-sixpence extra for hire and carmine; but I don’t do that myself, for I don’t consider it legitimate.’

Drawing herself up, as though she plumed herself greatly upon not resorting to these lures to catch sitters, Miss La Creevy applied herself, more intently, to her task: only raising her head occasionally, to look with unspeakable satisfaction at some touch she had just put in: and now and then giving Miss Nickleby to understand what particular feature she was at work upon, at the moment; ‘not,’ she expressly observed, ‘that you should make it up for painting, my dear, but because it’s our custom sometimes to tell sitters what part we are upon, in order that if there’s any particular expression they want introduced, they may throw it in, at the time, you know.’

‘And when,’ said Miss La Creevy, after a long silence, to wit, an interval of full a minute and a half, ‘when do you expect to see your uncle again?’

‘I scarcely know; I had expected to have seen him before now,’ replied Kate. ‘Soon I hope, for this state of uncertainty is worse than anything.’

‘I suppose he has money, hasn’t he?’ inquired Miss La Creevy.

‘He is very rich, I have heard,’ rejoined Kate. ‘I don’t know that he is, but I believe so.’

‘Ah, you may depend upon it he is, or he wouldn’t be so surly,’ remarked Miss La Creevy, who was an odd little mixture of shrewdness and simplicity. ‘When a man’s a bear, he is generally pretty independent.’

‘His manner is rough,’ said Kate.

‘Rough!’ cried Miss La Creevy, ‘a porcupine’s a featherbed to him! I never met with such a cross-grained old savage.’

‘It is only his manner, I believe,’ observed Kate, timidly; ‘he was disappointed in early life, I think I have heard, or has had his temper soured by some calamity. I should be sorry to think ill of him until I knew he deserved it.’

‘Well; that’s very right and proper,’ observed the miniature painter, ‘and Heaven forbid that I should be the cause of your doing so! But, now, mightn’t he, without feeling it himself, make you and your mama some nice little allowance that would keep you both comfortable until you were well married, and be a little fortune to her afterwards? What would a hundred a year for instance, be to him?’

‘I don’t know what it would be to him,’ said Kate, with energy, ‘but it would be that to me I would rather die than take.’

‘Heyday!’ cried Miss La Creevy.

‘A dependence upon him,’ said Kate, ‘would embitter my whole life. I should feel begging a far less degradation.’

‘Well!’ exclaimed Miss La Creevy. ‘This of a relation whom you will not hear an indifferent person speak ill of, my dear, sounds oddly enough, I confess.’

‘I dare say it does,’ replied Kate, speaking more gently, ‘indeed I am sure it must. I—I—only mean that with the feelings and recollection of better times upon me, I could not bear to live on anybody’s bounty—not his particularly, but anybody’s.’

Miss La Creevy looked slyly at her companion, as if she doubted whether Ralph himself were not the subject of dislike, but seeing that her young friend was distressed, made no remark.

‘I only ask of him,’ continued Kate, whose tears fell while she spoke, ‘that he will move so little out of his way, in my behalf, as to enable me by his recommendation—only by his recommendation—to earn, literally, my bread and remain with my mother. Whether we shall ever taste happiness again, depends upon the fortunes of my dear brother; but if he will do this, and Nicholas only tells us that he is well and cheerful, I shall be contented.’

As she ceased to speak, there was a rustling behind the screen which stood between her and the door, and some person knocked at the wainscot.’

‘Come in, whoever it is!’ cried Miss La Creevy.

The person complied, and, coming forward at once, gave to view the form and features of no less an individual than Mr. Ralph Nickleby himself.

‘Your servant, ladies,’ said Ralph, looking sharply at them by turns. ‘You were talking so loud, that I was unable to make you hear.’

When the man of business had a more than commonly vicious snarl lurking at his heart, he had a trick of almost concealing his eyes under their thick and protruding brows, for an instant, and then displaying them in their full keenness. As he did so now, and tried to keep down the smile which parted his thin compressed lips, and puckered up the bad lines about his mouth, they both felt certain that some part, if not the whole, of their recent conversation, had been overheard.

‘I called in, on my way upstairs, more than half expecting to find you here,’ said Ralph, addressing his niece, and looking contemptuously at the portrait. ‘Is that my niece’s portrait, ma’am?’

‘Yes it is, Mr. Nickleby,’ said Miss La Creevy, with a very sprightly air, ‘and between you and me and the post, sir, it will be a very nice portrait too, though I say it who am the painter.’

‘Don’t trouble yourself to show it to me, ma’am,’ cried Ralph, moving away, ‘I have no eye for likenesses. Is it nearly finished?’

‘Why, yes,’ replied Miss La Creevy, considering with the pencil end of her brush in her mouth. ‘Two sittings more will—’

‘Have them at once, ma’am,’ said Ralph. ‘She’ll have no time to idle over fooleries after tomorrow. Work, ma’am, work; we must all work. Have you let your lodgings, ma’am?’

‘I have not put a bill up yet, sir.’

‘Put it up at once, ma’am; they won’t want the rooms after this week, or if they do, can’t pay for them. Now, my dear, if you’re ready, we’ll lose no more time.’

With an assumption of kindness which sat worse upon him even than his usual manner, Mr. Ralph Nickleby motioned to the young lady to precede him, and bowing gravely to Miss La Creevy, closed the door and followed upstairs, where Mrs. Nickleby received him with many expressions of regard. Stopping them somewhat abruptly, Ralph waved his hand with an impatient gesture, and proceeded to the object of his visit.

‘I have found a situation for your daughter, ma’am,’ said Ralph.

‘Well,’ replied Mrs. Nickleby. ‘Now, I will say that that is only just what I have expected of you. “Depend upon it,” I said to Kate, only yesterday morning at breakfast, “that after your uncle has provided, in that most ready manner, for Nicholas, he will not leave us until he has done at least the same for you.” These were my very words, as near as I remember. Kate, my dear, why don’t you thank your—’

‘Let me proceed, ma’am, pray,’ said Ralph, interrupting his sister-in-law in the full torrent of her discourse.

‘Kate, my love, let your uncle proceed,’ said Mrs. Nickleby.

‘I am most anxious that he should, mama,’ rejoined Kate.

‘Well, my dear, if you are anxious that he should, you had better allow your uncle to say what he has to say, without interruption,’ observed Mrs Nickleby, with many small nods and frowns. ‘Your uncle’s time is very valuable, my dear; and however desirous you may be—and naturally desirous, as I am sure any affectionate relations who have seen so little of your uncle as we have, must naturally be to protract the pleasure of having him among us, still, we are bound not to be selfish, but to take into consideration the important nature of his occupations in the city.’

‘I am very much obliged to you, ma’am,’ said Ralph with a scarcely perceptible sneer. ‘An absence of business habits in this family leads, apparently, to a great waste of words before business—when it does come under consideration—is arrived at, at all.’

‘I fear it is so indeed,’ replied Mrs. Nickleby with a sigh. ‘Your poor brother—’

‘My poor brother, ma’am,’ interposed Ralph tartly, ‘had no idea what business was—was unacquainted, I verily believe, with the very meaning of the word.’

‘I fear he was,’ said Mrs. Nickleby, with her handkerchief to her eyes. ‘If it hadn’t been for me, I don’t know what would have become of him.’

What strange creatures we are! The slight bait so skilfully thrown out by Ralph, on their first interview, was dangling on the hook yet. At every small deprivation or discomfort which presented itself in the course of the four-and-twenty hours to remind her of her straitened and altered circumstances, peevish visions of her dower of one thousand pounds had arisen before Mrs. Nickleby’s mind, until, at last, she had come to persuade herself that of all her late husband’s creditors she was the worst used and the most to be pitied. And yet, she had loved him dearly for many years, and had no greater share of selfishness than is the usual lot of mortals. Such is the irritability of sudden poverty. A decent annuity would have restored her thoughts to their old train, at once.

‘Repining is of no use, ma’am,’ said Ralph. ‘Of all fruitless errands, sending a tear to look after a day that is gone is the most fruitless.’

‘So it is,’ sobbed Mrs. Nickleby. ‘So it is.’

‘As you feel so keenly, in your own purse and person, the consequences of inattention to business, ma’am,’ said Ralph, ‘I am sure you will impress upon your children the necessity of attaching themselves to it early in life.’

‘Of course I must see that,’ rejoined Mrs. Nickleby. ‘Sad experience, you know, brother-in-law.—Kate, my dear, put that down in the next letter to Nicholas, or remind me to do it if I write.’

Ralph paused for a few moments, and seeing that he had now made pretty sure of the mother, in case the daughter objected to his proposition, went on to say:

‘The situation that I have made interest to procure, ma’am, is with—with a milliner and dressmaker, in short.’

‘A milliner!’ cried Mrs. Nickleby.

‘A milliner and dressmaker, ma’am,’ replied Ralph. ‘Dressmakers in London, as I need not remind you, ma’am, who are so well acquainted with all matters in the ordinary routine of life, make large fortunes, keep equipages, and become persons of great wealth and fortune.’

Now, the first idea called up in Mrs. Nickleby’s mind by the words milliner and dressmaker were connected with certain wicker baskets lined with black oilskin, which she remembered to have seen carried to and fro in the streets; but, as Ralph proceeded, these disappeared, and were replaced by visions of large houses at the West end, neat private carriages, and a banker’s book; all of which images succeeded each other with such rapidity, that he had no sooner finished speaking, than she nodded her head and said ‘Very true,’ with great appearance of satisfaction.

‘What your uncle says is very true, Kate, my dear,’ said Mrs. Nickleby. ‘I recollect when your poor papa and I came to town after we were married, that a young lady brought me home a chip cottage-bonnet, with white and green trimming, and green persian lining, in her own carriage, which drove up to the door full gallop;—at least, I am not quite certain whether it was her own carriage or a hackney chariot, but I remember very well that the horse dropped down dead as he was turning round, and that your poor papa said he hadn’t had any corn for a fortnight.’

This anecdote, so strikingly illustrative of the opulence of milliners, was not received with any great demonstration of feeling, inasmuch as Kate hung down her head while it was relating, and Ralph manifested very intelligible symptoms of extreme impatience.

‘The lady’s name,’ said Ralph, hastily striking in, ‘is Mantalini—Madame Mantalini. I know her. She lives near Cavendish Square. If your daughter is disposed to try after the situation, I’ll take her there directly.’

‘Have you nothing to say to your uncle, my love?’ inquired Mrs. Nickleby.

‘A great deal,’ replied Kate; ‘but not now. I would rather speak to him when we are alone;—it will save his time if I thank him and say what I wish to say to him, as we walk along.’

With these words, Kate hurried away, to hide the traces of emotion that were stealing down her face, and to prepare herself for the walk, while Mrs. Nickleby amused her brother-in-law by giving him, with many tears, a detailed account of the dimensions of a rosewood cabinet piano they had possessed in their days of affluence, together with a minute description of eight drawing-room chairs, with turned legs and green chintz squabs to match the curtains, which had cost two pounds fifteen shillings apiece, and had gone at the sale for a mere nothing.

These reminiscences were at length cut short by Kate’s return in her walking dress, when Ralph, who had been fretting and fuming during the whole time of her absence, lost no time, and used very little ceremony, in descending into the street.

‘Now,’ he said, taking her arm, ‘walk as fast as you can, and you’ll get into the step that you’ll have to walk to business with, every morning.’ So saying, he led Kate off, at a good round pace, towards Cavendish Square.

‘I am very much obliged to you, uncle,’ said the young lady, after they had hurried on in silence for some time; ‘very.’

‘I’m glad to hear it,’ said Ralph. ‘I hope you’ll do your duty.’

‘I will try to please, uncle,’ replied Kate: ‘indeed I—’

‘Don’t begin to cry,’ growled Ralph; ‘I hate crying.’

‘It’s very foolish, I know, uncle,’ began poor Kate.

‘It is,’ replied Ralph, stopping her short, ‘and very affected besides. Let me see no more of it.’

Perhaps this was not the best way to dry the tears of a young and sensitive female, about to make her first entry on an entirely new scene of life, among cold and uninterested strangers; but it had its effect notwithstanding. Kate coloured deeply, breathed quickly for a few moments, and then walked on with a firmer and more determined step.

It was a curious contrast to see how the timid country girl shrunk through the crowd that hurried up and down the streets, giving way to the press of people, and clinging closely to Ralph as though she feared to lose him in the throng; and how the stern and hard-featured man of business went doggedly on, elbowing the passengers aside, and now and then exchanging a gruff salutation with some passing acquaintance, who turned to look back upon his pretty charge, with looks expressive of surprise, and seemed to wonder at the ill-assorted companionship. But, it would have been a stranger contrast still, to have read the hearts that were beating side by side; to have laid bare the gentle innocence of the one, and the rugged villainy of the other; to have hung upon the guileless thoughts of the affectionate girl, and been amazed that, among all the wily plots and calculations of the old man, there should not be one word or figure denoting thought of death or of the grave. But so it was; and stranger still—though this is a thing of every day—the warm young heart palpitated with a thousand anxieties and apprehensions, while that of the old worldly man lay rusting in its cell, beating only as a piece of cunning mechanism, and yielding no one throb of hope, or fear, or love, or care, for any living thing.

‘Uncle,’ said Kate, when she judged they must be near their destination, ‘I must ask one question of you. I am to live at home?’

‘At home!’ replied Ralph; ‘where’s that?’

‘I mean with my mother—The Widow,’ said Kate emphatically.

‘You will live, to all intents and purposes, here,’ rejoined Ralph; ‘for here you will take your meals, and here you will be from morning till night—occasionally perhaps till morning again.’

‘But at night, I mean,’ said Kate; ‘I cannot leave her, uncle. I must have some place that I can call a home; it will be wherever she is, you know, and may be a very humble one.’

‘May be!’ said Ralph, walking faster, in the impatience provoked by the remark; ‘must be, you mean. May be a humble one! Is the girl mad?’

‘The word slipped from my lips, I did not mean it indeed,’ urged Kate.

‘I hope not,’ said Ralph.

‘But my question, uncle; you have not answered it.’

‘Why, I anticipated something of the kind,’ said Ralph; ‘and—though I object very strongly, mind—have provided against it. I spoke of you as an out-of-door worker; so you will go to this home that may be humble, every night.’

There was comfort in this. Kate poured forth many thanks for her uncle’s consideration, which Ralph received as if he had deserved them all, and they arrived without any further conversation at the dressmaker’s door, which displayed a very large plate, with Madame Mantalini’s name and occupation, and was approached by a handsome flight of steps. There was a shop to the house, but it was let off to an importer of otto of roses. Madame Mantalini’s shows-rooms were on the first-floor: a fact which was notified to the nobility and gentry by the casual exhibition, near the handsomely curtained windows, of two or three elegant bonnets of the newest fashion, and some costly garments in the most approved taste.

A liveried footman opened the door, and in reply to Ralph’s inquiry whether Madame Mantalini was at home, ushered them, through a handsome hall and up a spacious staircase, into the show saloon, which comprised two spacious drawing-rooms, and exhibited an immense variety of superb dresses and materials for dresses: some arranged on stands, others laid carelessly on sofas, and others again, scattered over the carpet, hanging on the cheval-glasses, or mingling, in some other way, with the rich furniture of various descriptions, which was profusely displayed.

They waited here a much longer time than was agreeable to Mr. Ralph Nickleby, who eyed the gaudy frippery about him with very little concern, and was at length about to pull the bell, when a gentleman suddenly popped his head into the room, and, seeing somebody there, as suddenly popped it out again.

‘Here. Hollo!’ cried Ralph. ‘Who’s that?’

At the sound of Ralph’s voice, the head reappeared, and the mouth, displaying a very long row of very white teeth, uttered in a mincing tone the words, ‘Demmit. What, Nickleby! oh, demmit!’ Having uttered which ejaculations, the gentleman advanced, and shook hands with Ralph, with great warmth. He was dressed in a gorgeous morning gown, with a waistcoat and Turkish trousers of the same pattern, a pink silk neckerchief, and bright green slippers, and had a very copious watch-chain wound round his body. Moreover, he had whiskers and a moustache, both dyed black and gracefully curled.

‘Demmit, you don’t mean to say you want me, do you, demmit?’ said this gentleman, smiting Ralph on the shoulder.

‘Not yet,’ said Ralph, sarcastically.

‘Ha! ha! demmit,’ cried the gentleman; when, wheeling round to laugh with greater elegance, he encountered Kate Nickleby, who was standing near.

‘My niece,’ said Ralph.

‘I remember,’ said the gentleman, striking his nose with the knuckle of his forefinger as a chastening for his forgetfulness. ‘Demmit, I remember what you come for. Step this way, Nickleby; my dear, will you follow me? Ha! ha! They all follow me, Nickleby; always did, demmit, always.’

Giving loose to the playfulness of his imagination, after this fashion, the gentleman led the way to a private sitting-room on the second floor, scarcely less elegantly furnished than the apartment below, where the presence of a silver coffee-pot, an egg-shell, and sloppy china for one, seemed to show that he had just breakfasted.

‘Sit down, my dear,’ said the gentleman: first staring Miss Nickleby out of countenance, and then grinning in delight at the achievement. ‘This cursed high room takes one’s breath away. These infernal sky parlours—I’m afraid I must move, Nickleby.’

‘I would, by all means,’ replied Ralph, looking bitterly round.

‘What a demd rum fellow you are, Nickleby,’ said the gentleman, ‘the demdest, longest-headed, queerest-tempered old coiner of gold and silver ever was—demmit.’

Having complimented Ralph to this effect, the gentleman rang the bell, and stared at Miss Nickleby until it was answered, when he left off to bid the man desire his mistress to come directly; after which, he began again, and left off no more until Madame Mantalini appeared.

The dressmaker was a buxom person, handsomely dressed and rather good-looking, but much older than the gentleman in the Turkish trousers, whom she had wedded some six months before. His name was originally Muntle; but it had been converted, by an easy transition, into Mantalini: the lady rightly considering that an English appellation would be of serious injury to the business. He had married on his whiskers; upon which property he had previously subsisted, in a genteel manner, for some years; and which he had recently improved, after patient cultivation by the addition of a moustache, which promised to secure him an easy independence: his share in the labours of the business being at present confined to spending the money, and occasionally, when that ran short, driving to Mr. Ralph Nickleby to procure discount—at a percentage—for the customers’ bills.

‘My life,’ said Mr. Mantalini, ‘what a demd devil of a time you have been!’

‘I didn’t even know Mr. Nickleby was here, my love,’ said Madame Mantalini.

‘Then what a doubly demd infernal rascal that footman must be, my soul,’ remonstrated Mr. Mantalini.

‘My dear,’ said Madame, ‘that is entirely your fault.’

‘My fault, my heart’s joy?’

‘Certainly,’ returned the lady; ‘what can you expect, dearest, if you will not correct the man?’

‘Correct the man, my soul’s delight!’

‘Yes; I am sure he wants speaking to, badly enough,’ said Madame, pouting.

‘Then do not vex itself,’ said Mr. Mantalini; ‘he shall be horse-whipped till he cries out demnebly.’ With this promise Mr. Mantalini kissed Madame Mantalini, and, after that performance, Madame Mantalini pulled Mr Mantalini playfully by the ear: which done, they descended to business.

‘Now, ma’am,’ said Ralph, who had looked on, at all this, with such scorn as few men can express in looks, ‘this is my niece.’

‘Just so, Mr. Nickleby,’ replied Madame Mantalini, surveying Kate from head to foot, and back again. ‘Can you speak French, child?’

‘Yes, ma’am,’ replied Kate, not daring to look up; for she felt that the eyes of the odious man in the dressing-gown were directed towards her.

‘Like a demd native?’ asked the husband.

Miss Nickleby offered no reply to this inquiry, but turned her back upon the questioner, as if addressing herself to make answer to what his wife might demand.

‘We keep twenty young women constantly employed in the establishment,’ said Madame.

‘Indeed, ma’am!’ replied Kate, timidly.

‘Yes; and some of ‘em demd handsome, too,’ said the master.

‘Mantalini!’ exclaimed his wife, in an awful voice.

‘My senses’ idol!’ said Mantalini.

‘Do you wish to break my heart?’

‘Not for twenty thousand hemispheres populated with—with—with little ballet-dancers,’ replied Mantalini in a poetical strain.

‘Then you will, if you persevere in that mode of speaking,’ said his wife. ‘What can Mr. Nickleby think when he hears you?’

‘Oh! Nothing, ma’am, nothing,’ replied Ralph. ‘I know his amiable nature, and yours,—mere little remarks that give a zest to your daily intercourse—lovers’ quarrels that add sweetness to those domestic joys which promise to last so long—that’s all; that’s all.’

If an iron door could be supposed to quarrel with its hinges, and to make a firm resolution to open with slow obstinacy, and grind them to powder in the process, it would emit a pleasanter sound in so doing, than did these words in the rough and bitter voice in which they were uttered by Ralph. Even Mr. Mantalini felt their influence, and turning affrighted round, exclaimed: ‘What a demd horrid croaking!’

‘You will pay no attention, if you please, to what Mr. Mantalini says,’ observed his wife, addressing Miss Nickleby.

‘I do not, ma’am,’ said Kate, with quiet contempt.

‘Mr. Mantalini knows nothing whatever about any of the young women,’ continued Madame, looking at her husband, and speaking to Kate. ‘If he has seen any of them, he must have seen them in the street, going to, or returning from, their work, and not here. He was never even in the room. I do not allow it. What hours of work have you been accustomed to?’

‘I have never yet been accustomed to work at all, ma’am,’ replied Kate, in a low voice.

‘For which reason she’ll work all the better now,’ said Ralph, putting in a word, lest this confession should injure the negotiation.

‘I hope so,’ returned Madame Mantalini; ‘our hours are from nine to nine, with extra work when we’re very full of business, for which I allow payment as overtime.’

Kate bowed her head, to intimate that she heard, and was satisfied.

‘Your meals,’ continued Madame Mantalini, ‘that is, dinner and tea, you will take here. I should think your wages would average from five to seven shillings a week; but I can’t give you any certain information on that point, until I see what you can do.’

Kate bowed her head again.

‘If you’re ready to come,’ said Madame Mantalini, ‘you had better begin on Monday morning at nine exactly, and Miss Knag the forewoman shall then have directions to try you with some easy work at first. Is there anything more, Mr. Nickleby?’

‘Nothing more, ma’am,’ replied Ralph, rising.

‘Then I believe that’s all,’ said the lady. Having arrived at this natural conclusion, she looked at the door, as if she wished to be gone, but hesitated notwithstanding, as though unwilling to leave to Mr. Mantalini the sole honour of showing them downstairs. Ralph relieved her from her perplexity by taking his departure without delay: Madame Mantalini making many gracious inquiries why he never came to see them; and Mr. Mantalini anathematising the stairs with great volubility as he followed them down, in the hope of inducing Kate to look round,—a hope, however, which was destined to remain ungratified.

‘There!’ said Ralph when they got into the street; ‘now you’re provided for.’

Kate was about to thank him again, but he stopped her.

‘I had some idea,’ he said, ‘of providing for your mother in a pleasant part of the country—(he had a presentation to some almshouses on the borders of Cornwall, which had occurred to him more than once)—but as you want to be together, I must do something else for her. She has a little money?’

‘A very little,’ replied Kate.

‘A little will go a long way if it’s used sparingly,’ said Ralph. ‘She must see how long she can make it last, living rent free. You leave your lodgings on Saturday?’

‘You told us to do so, uncle.’

‘Yes; there is a house empty that belongs to me, which I can put you into till it is let, and then, if nothing else turns up, perhaps I shall have another. You must live there.’

‘Is it far from here, sir?’ inquired Kate.

‘Pretty well,’ said Ralph; ‘in another quarter of the town—at the East end; but I’ll send my clerk down to you, at five o’clock on Saturday, to take you there. Goodbye. You know your way? Straight on.’

Coldly shaking his niece’s hand, Ralph left her at the top of Regent Street, and turned down a by-thoroughfare, intent on schemes of money-getting. Kate walked sadly back to their lodgings in the Strand.