If Bella thought, as she glanced at the mighty Bank, how agreeable it would be to have an hour’s gardening there, with a bright copper shovel, among the money, still she was not in an avaricious vein. Much improved in that respect, and with certain half-formed images which had little gold in their composition, dancing before her bright eyes, she arrived in the drug-flavoured region of Mincing Lane, with the sensation of having just opened a drawer in a chemist’s shop.

The counting-house of Chicksey, Veneering, and Stobbles was pointed out by an elderly female accustomed to the care of offices, who dropped upon Bella out of a public-house, wiping her mouth, and accounted for its humidity on natural principles well known to the physical sciences, by explaining that she had looked in at the door to see what o’clock it was. The counting-house was a wall-eyed ground floor by a dark gateway, and Bella was considering, as she approached it, could there be any precedent in the City for her going in and asking for R. Wilfer, when whom should she see, sitting at one of the windows with the plate-glass sash raised, but R. Wilfer himself, preparing to take a slight refection.

On approaching nearer, Bella discerned that the refection had the appearance of a small cottage-loaf and a pennyworth of milk. Simultaneously with this discovery on her part, her father discovered her, and invoked the echoes of Mincing Lane to exclaim ‘My gracious me!’

He then came cherubically flying out without a hat, and embraced her, and handed her in. ‘For it’s after hours and I am all alone, my dear,’ he explained, ‘and am having—as I sometimes do when they are all gone—a quiet tea.’

Looking round the office, as if her father were a captive and this his cell, Bella hugged him and choked him to her heart’s content.

‘I never was so surprised, my dear!’ said her father. ‘I couldn’t believe my eyes. Upon my life, I thought they had taken to lying! The idea of your coming down the Lane yourself! Why didn’t you send the footman down the Lane, my dear?’

‘I have brought no footman with me, Pa.’

‘Oh indeed! But you have brought the elegant turn-out, my love?’

‘No, Pa.’

‘You never can have walked, my dear?’

‘Yes, I have, Pa.’

He looked so very much astonished, that Bella could not make up her mind to break it to him just yet.

‘The consequence is, Pa, that your lovely woman feels a little faint, and would very much like to share your tea.’

The cottage loaf and the pennyworth of milk had been set forth on a sheet of paper on the window-seat. The cherubic pocket-knife, with the first bit of the loaf still on its point, lay beside them where it had been hastily thrown down. Bella took the bit off, and put it in her mouth. ‘My dear child,’ said her father, ‘the idea of your partaking of such lowly fare! But at least you must have your own loaf and your own penn’orth. One moment, my dear. The Dairy is just over the way and round the corner.’

Regardless of Bella’s dissuasions he ran out, and quickly returned with the new supply. ‘My dear child,’ he said, as he spread it on another piece of paper before her, ‘the idea of a splendid—!’ and then looked at her figure, and stopped short.

‘What’s the matter, Pa?’

‘—of a splendid female,’ he resumed more slowly, ‘putting up with such accommodation as the present!—Is that a new dress you have on, my dear?’

‘No, Pa, an old one. Don’t you remember it?’

‘Why, I thought I remembered it, my dear!’

‘You should, for you bought it, Pa.’

‘Yes, I thought I bought it my dear!’ said the cherub, giving himself a little shake, as if to rouse his faculties.

‘And have you grown so fickle that you don’t like your own taste, Pa dear?’

‘Well, my love,’ he returned, swallowing a bit of the cottage loaf with considerable effort, for it seemed to stick by the way: ‘I should have thought it was hardly sufficiently splendid for existing circumstances.’

‘And so, Pa,’ said Bella, moving coaxingly to his side instead of remaining opposite, ‘you sometimes have a quiet tea here all alone? I am not in the tea’s way, if I draw my arm over your shoulder like this, Pa?’

‘Yes, my dear, and no, my dear. Yes to the first question, and Certainly Not to the second. Respecting the quiet tea, my dear, why you see the occupations of the day are sometimes a little wearing; and if there’s nothing interposed between the day and your mother, why she is sometimes a little wearing, too.’

‘I know, Pa.’

‘Yes, my dear. So sometimes I put a quiet tea at the window here, with a little quiet contemplation of the Lane (which comes soothing), between the day, and domestic—’

‘Bliss,’ suggested Bella, sorrowfully.

‘And domestic Bliss,’ said her father, quite contented to accept the phrase.

Bella kissed him. ‘And it is in this dark dingy place of captivity, poor dear, that you pass all the hours of your life when you are not at home?’

‘Not at home, or not on the road there, or on the road here, my love. Yes. You see that little desk in the corner?’

‘In the dark corner, furthest both from the light and from the fireplace? The shabbiest desk of all the desks?’

‘Now, does it really strike you in that point of view, my dear?’ said her father, surveying it artistically with his head on one side: ‘that’s mine. That’s called Rumty’s Perch.’

‘Whose Perch?’ asked Bella with great indignation.

‘Rumty’s. You see, being rather high and up two steps they call it a Perch. And they call me Rumty.’

‘How dare they!’ exclaimed Bella.

‘They’re playful, Bella my dear; they’re playful. They’re more or less younger than I am, and they’re playful. What does it matter? It might be Surly, or Sulky, or fifty disagreeable things that I really shouldn’t like to be considered. But Rumty! Lor, why not Rumty?’

To inflict a heavy disappointment on this sweet nature, which had been, through all her caprices, the object of her recognition, love, and admiration from infancy, Bella felt to be the hardest task of her hard day. ‘I should have done better,’ she thought, ‘to tell him at first; I should have done better to tell him just now, when he had some slight misgiving; he is quite happy again, and I shall make him wretched.’

He was falling back on his loaf and milk, with the pleasantest composure, and Bella stealing her arm a little closer about him, and at the same time sticking up his hair with an irresistible propensity to play with him founded on the habit of her whole life, had prepared herself to say: ‘Pa dear, don’t be cast down, but I must tell you something disagreeable!’ when he interrupted her in an unlooked-for manner.

‘My gracious me!’ he exclaimed, invoking the Mincing Lane echoes as before. ‘This is very extraordinary!’

‘What is, Pa?’

‘Why here’s Mr Rokesmith now!’

‘No, no, Pa, no,’ cried Bella, greatly flurried. ‘Surely not.’

‘Yes there is! Look here!’

Sooth to say, Mr Rokesmith not only passed the window, but came into the counting-house. And not only came into the counting-house, but, finding himself alone there with Bella and her father, rushed at Bella and caught her in his arms, with the rapturous words ‘My dear, dear girl; my gallant, generous, disinterested, courageous, noble girl!’ And not only that even, (which one might have thought astonishment enough for one dose), but Bella, after hanging her head for a moment, lifted it up and laid it on his breast, as if that were her head’s chosen and lasting resting-place!

‘I knew you would come to him, and I followed you,’ said Rokesmith. ‘My love, my life! You are mine?’

To which Bella responded, ‘Yes, I am yours if you think me worth taking!’ And after that, seemed to shrink to next to nothing in the clasp of his arms, partly because it was such a strong one on his part, and partly because there was such a yielding to it on hers.

The cherub, whose hair would have done for itself under the influence of this amazing spectacle, what Bella had just now done for it, staggered back into the window-seat from which he had risen, and surveyed the pair with his eyes dilated to their utmost.

‘But we must think of dear Pa,’ said Bella; ‘I haven’t told dear Pa; let us speak to Pa.’ Upon which they turned to do so.

‘I wish first, my dear,’ remarked the cherub faintly, ‘that you’d have the kindness to sprinkle me with a little milk, for I feel as if I was—Going.’

In fact, the good little fellow had become alarmingly limp, and his senses seemed to be rapidly escaping, from the knees upward. Bella sprinkled him with kisses instead of milk, but gave him a little of that article to drink; and he gradually revived under her caressing care.

‘We’ll break it to you gently, dearest Pa,’ said Bella.

‘My dear,’ returned the cherub, looking at them both, ‘you broke so much in the first—Gush, if I may so express myself—that I think I am equal to a good large breakage now.’

‘Mr Wilfer,’ said John Rokesmith, excitedly and joyfully, ‘Bella takes me, though I have no fortune, even no present occupation; nothing but what I can get in the life before us. Bella takes me!’

‘Yes, I should rather have inferred, my dear sir,’ returned the cherub feebly, ‘that Bella took you, from what I have within these few minutes remarked.’

‘You don’t know, Pa,’ said Bella, ‘how ill I have used him!’

‘You don’t know, sir,’ said Rokesmith, ‘what a heart she has!’

‘You don’t know, Pa,’ said Bella, ‘what a shocking creature I was growing, when he saved me from myself!’

‘You don’t know, sir,’ said Rokesmith, ‘what a sacrifice she has made for me!’

‘My dear Bella,’ replied the cherub, still pathetically scared, ‘and my dear John Rokesmith, if you will allow me so to call you—’

‘Yes do, Pa, do!’ urged Bella. ‘I allow you, and my will is his law. Isn’t it—dear John Rokesmith?’

There was an engaging shyness in Bella, coupled with an engaging tenderness of love and confidence and pride, in thus first calling him by name, which made it quite excusable in John Rokesmith to do what he did. What he did was, once more to give her the appearance of vanishing as aforesaid.

‘I think, my dears,’ observed the cherub, ‘that if you could make it convenient to sit one on one side of me, and the other on the other, we should get on rather more consecutively, and make things rather plainer. John Rokesmith mentioned, a while ago, that he had no present occupation.’

‘None,’ said Rokesmith.

‘No, Pa, none,’ said Bella.

‘From which I argue,’ proceeded the cherub, ‘that he has left Mr Boffin?’

‘Yes, Pa. And so—’

‘Stop a bit, my dear. I wish to lead up to it by degrees. And that Mr Boffin has not treated him well?’

‘Has treated him most shamefully, dear Pa!’ cried Bella with a flashing face.

‘Of which,’ pursued the cherub, enjoining patience with his hand, ‘a certain mercenary young person distantly related to myself, could not approve? Am I leading up to it right?’

‘Could not approve, sweet Pa,’ said Bella, with a tearful laugh and a joyful kiss.

‘Upon which,’ pursued the cherub, ‘the certain mercenary young person distantly related to myself, having previously observed and mentioned to myself that prosperity was spoiling Mr Boffin, felt that she must not sell her sense of what was right and what was wrong, and what was true and what was false, and what was just and what was unjust, for any price that could be paid to her by any one alive? Am I leading up to it right?’

With another tearful laugh Bella joyfully kissed him again.

‘And therefore—and therefore,’ the cherub went on in a glowing voice, as Bella’s hand stole gradually up his waistcoat to his neck, ‘this mercenary young person distantly related to myself, refused the price, took off the splendid fashions that were part of it, put on the comparatively poor dress that I had last given her, and trusting to my supporting her in what was right, came straight to me. Have I led up to it?’

Bella’s hand was round his neck by this time, and her face was on it.

‘The mercenary young person distantly related to myself,’ said her good father, ‘did well! The mercenary young person distantly related to myself, did not trust to me in vain! I admire this mercenary young person distantly related to myself, more in this dress than if she had come to me in China silks, Cashmere shawls, and Golconda diamonds. I love this young person dearly. I say to the man of this young person’s heart, out of my heart and with all of it, “My blessing on this engagement betwixt you, and she brings you a good fortune when she brings you the poverty she has accepted for your sake and the honest truth’s!”’

The stanch little man’s voice failed him as he gave John Rokesmith his hand, and he was silent, bending his face low over his daughter. But, not for long. He soon looked up, saying in a sprightly tone:

‘And now, my dear child, if you think you can entertain John Rokesmith for a minute and a half, I’ll run over to the Dairy, and fetch him a cottage loaf and a drink of milk, that we may all have tea together.’

It was, as Bella gaily said, like the supper provided for the three nursery hobgoblins at their house in the forest, without their thunderous low growlings of the alarming discovery, ‘Somebody’s been drinking my milk!’ It was a delicious repast; by far the most delicious that Bella, or John Rokesmith, or even R. Wilfer had ever made. The uncongenial oddity of its surroundings, with the two brass knobs of the iron safe of Chicksey, Veneering, and Stobbles staring from a corner, like the eyes of some dull dragon, only made it the more delightful.

‘To think,’ said the cherub, looking round the office with unspeakable enjoyment, ‘that anything of a tender nature should come off here, is what tickles me. To think that ever I should have seen my Bella folded in the arms of her future husband, here, you know!’

It was not until the cottage loaves and the milk had for some time disappeared, and the foreshadowings of night were creeping over Mincing Lane, that the cherub by degrees became a little nervous, and said to Bella, as he cleared his throat:

‘Hem!—Have you thought at all about your mother, my dear?’

‘Yes, Pa.’

‘And your sister Lavvy, for instance, my dear?’

‘Yes, Pa. I think we had better not enter into particulars at home. I think it will be quite enough to say that I had a difference with Mr Boffin, and have left for good.’

‘John Rokesmith being acquainted with your Ma, my love,’ said her father, after some slight hesitation, ‘I need have no delicacy in hinting before him that you may perhaps find your Ma a little wearing.’

‘A little, patient Pa?’ said Bella with a tuneful laugh: the tune fuller for being so loving in its tone.

‘Well! We’ll say, strictly in confidence among ourselves, wearing; we won’t qualify it,’ the cherub stoutly admitted. ‘And your sister’s temper is wearing.’

‘I don’t mind, Pa.’

‘And you must prepare yourself you know, my precious,’ said her father, with much gentleness, ‘for our looking very poor and meagre at home, and being at the best but very uncomfortable, after Mr Boffin’s house.’

‘I don’t mind, Pa. I could bear much harder trials—for John.’

The closing words were not so softly and blushingly said but that John heard them, and showed that he heard them by again assisting Bella to another of those mysterious disappearances.

‘Well!’ said the cherub gaily, and not expressing disapproval, ‘when you—when you come back from retirement, my love, and reappear on the surface, I think it will be time to lock up and go.’

If the counting-house of Chicksey, Veneering, and Stobbles had ever been shut up by three happier people, glad as most people were to shut it up, they must have been superlatively happy indeed. But first Bella mounted upon Rumty’s Perch, and said, ‘Show me what you do here all day long, dear Pa. Do you write like this?’ laying her round cheek upon her plump left arm, and losing sight of her pen in waves of hair, in a highly unbusiness-like manner. Though John Rokesmith seemed to like it.

So, the three hobgoblins, having effaced all traces of their feast, and swept up the crumbs, came out of Mincing Lane to walk to Holloway; and if two of the hobgoblins didn’t wish the distance twice as long as it was, the third hobgoblin was much mistaken. Indeed, that modest spirit deemed himself so much in the way of their deep enjoyment of the journey, that he apologetically remarked: ‘I think, my dears, I’ll take the lead on the other side of the road, and seem not to belong to you.’ Which he did, cherubically strewing the path with smiles, in the absence of flowers.

It was almost ten o’clock when they stopped within view of Wilfer Castle; and then, the spot being quiet and deserted, Bella began a series of disappearances which threatened to last all night.

‘I think, John,’ the cherub hinted at last, ‘that if you can spare me the young person distantly related to myself, I’ll take her in.’

‘I can’t spare her,’ answered John, ‘but I must lend her to you.—My Darling!’ A word of magic which caused Bella instantly to disappear again.

‘Now, dearest Pa,’ said Bella, when she became visible, ‘put your hand in mine, and we’ll run home as fast as ever we can run, and get it over. Now, Pa. Once!—’

‘My dear,’ the cherub faltered, with something of a craven air, ‘I was going to observe that if your mother—’

‘You mustn’t hang back, sir, to gain time,’ cried Bella, putting out her right foot; ‘do you see that, sir? That’s the mark; come up to the mark, sir. Once! Twice! Three times and away, Pa!’ Off she skimmed, bearing the cherub along, nor ever stopped, nor suffered him to stop, until she had pulled at the bell. ‘Now, dear Pa,’ said Bella, taking him by both ears as if he were a pitcher, and conveying his face to her rosy lips, ‘we are in for it!’

Miss Lavvy came out to open the gate, waited on by that attentive cavalier and friend of the family, Mr George Sampson. ‘Why, it’s never Bella!’ exclaimed Miss Lavvy starting back at the sight. And then bawled, ‘Ma! Here’s Bella!’

This produced, before they could get into the house, Mrs Wilfer. Who, standing in the portal, received them with ghostly gloom, and all her other appliances of ceremony.

‘My child is welcome, though unlooked for,’ said she, at the time presenting her cheek as if it were a cool slate for visitors to enrol themselves upon. ‘You too, R. W., are welcome, though late. Does the male domestic of Mrs Boffin hear me there?’ This deep-toned inquiry was cast forth into the night, for response from the menial in question.

‘There is no one waiting, Ma, dear,’ said Bella.

‘There is no one waiting?’ repeated Mrs Wilfer in majestic accents.

‘No, Ma, dear.’

A dignified shiver pervaded Mrs Wilfer’s shoulders and gloves, as who should say, ‘An Enigma!’ and then she marched at the head of the procession to the family keeping-room, where she observed:

‘Unless, R. W.‘: who started on being solemnly turned upon: ‘you have taken the precaution of making some addition to our frugal supper on your way home, it will prove but a distasteful one to Bella. Cold neck of mutton and a lettuce can ill compete with the luxuries of Mr Boffin’s board.’

‘Pray don’t talk like that, Ma dear,’ said Bella; ‘Mr Boffin’s board is nothing to me.’

But, here Miss Lavinia, who had been intently eyeing Bella’s bonnet, struck in with ‘Why, Bella!’

‘Yes, Lavvy, I know.’

The Irrepressible lowered her eyes to Bella’s dress, and stooped to look at it, exclaiming again: ‘Why, Bella!’

‘Yes, Lavvy, I know what I have got on. I was going to tell Ma when you interrupted. I have left Mr Boffin’s house for good, Ma, and I have come home again.’

Mrs Wilfer spake no word, but, having glared at her offspring for a minute or two in an awful silence, retired into her corner of state backward, and sat down: like a frozen article on sale in a Russian market.

‘In short, dear Ma,’ said Bella, taking off the depreciated bonnet and shaking out her hair, ‘I have had a very serious difference with Mr Boffin on the subject of his treatment of a member of his household, and it’s a final difference, and there’s an end of all.’

‘And I am bound to tell you, my dear,’ added R. W., submissively, ‘that Bella has acted in a truly brave spirit, and with a truly right feeling. And therefore I hope, my dear, you’ll not allow yourself to be greatly disappointed.’

‘George!’ said Miss Lavvy, in a sepulchral, warning voice, founded on her mother’s; ‘George Sampson, speak! What did I tell you about those Boffins?’

Mr Sampson perceiving his frail bark to be labouring among shoals and breakers, thought it safest not to refer back to any particular thing that he had been told, lest he should refer back to the wrong thing. With admirable seamanship he got his bark into deep water by murmuring ‘Yes indeed.’

‘Yes! I told George Sampson, as George Sampson tells you,’ said Miss Lavvy, ‘that those hateful Boffins would pick a quarrel with Bella, as soon as her novelty had worn off. Have they done it, or have they not? Was I right, or was I wrong? And what do you say to us, Bella, of your Boffins now?’

‘Lavvy and Ma,’ said Bella, ‘I say of Mr and Mrs Boffin what I always have said; and I always shall say of them what I always have said. But nothing will induce me to quarrel with any one to-night. I hope you are not sorry to see me, Ma dear,’ kissing her; ‘and I hope you are not sorry to see me, Lavvy,’ kissing her too; ‘and as I notice the lettuce Ma mentioned, on the table, I’ll make the salad.’

Bella playfully setting herself about the task, Mrs Wilfer’s impressive countenance followed her with glaring eyes, presenting a combination of the once popular sign of the Saracen’s Head, with a piece of Dutch clock-work, and suggesting to an imaginative mind that from the composition of the salad, her daughter might prudently omit the vinegar. But no word issued from the majestic matron’s lips. And this was more terrific to her husband (as perhaps she knew) than any flow of eloquence with which she could have edified the company.

‘Now, Ma dear,’ said Bella in due course, ‘the salad’s ready, and it’s past supper-time.’

Mrs Wilfer rose, but remained speechless. ‘George!’ said Miss Lavinia in her voice of warning, ‘Ma’s chair!’ Mr Sampson flew to the excellent lady’s back, and followed her up close chair in hand, as she stalked to the banquet. Arrived at the table, she took her rigid seat, after favouring Mr Sampson with a glare for himself, which caused the young gentleman to retire to his place in much confusion.

The cherub not presuming to address so tremendous an object, transacted her supper through the agency of a third person, as ‘Mutton to your Ma, Bella, my dear’; and ‘Lavvy, I dare say your Ma would take some lettuce if you were to put it on her plate.’ Mrs Wilfer’s manner of receiving those viands was marked by petrified absence of mind; in which state, likewise, she partook of them, occasionally laying down her knife and fork, as saying within her own spirit, ‘What is this I am doing?’ and glaring at one or other of the party, as if in indignant search of information. A magnetic result of such glaring was, that the person glared at could not by any means successfully pretend to be ignorant of the fact: so that a bystander, without beholding Mrs Wilfer at all, must have known at whom she was glaring, by seeing her refracted from the countenance of the beglared one.

Miss Lavinia was extremely affable to Mr Sampson on this special occasion, and took the opportunity of informing her sister why.

‘It was not worth troubling you about, Bella, when you were in a sphere so far removed from your family as to make it a matter in which you could be expected to take very little interest,’ said Lavinia with a toss of her chin; ‘but George Sampson is paying his addresses to me.’

Bella was glad to hear it. Mr Sampson became thoughtfully red, and felt called upon to encircle Miss Lavinia’s waist with his arm; but, encountering a large pin in the young lady’s belt, scarified a finger, uttered a sharp exclamation, and attracted the lightning of Mrs Wilfer’s glare.

‘George is getting on very well,’ said Miss Lavinia which might not have been supposed at the moment—‘and I dare say we shall be married, one of these days. I didn’t care to mention it when you were with your Bof—’ here Miss Lavinia checked herself in a bounce, and added more placidly, ‘when you were with Mr and Mrs Boffin; but now I think it sisterly to name the circumstance.’

‘Thank you, Lavvy dear. I congratulate you.’

‘Thank you, Bella. The truth is, George and I did discuss whether I should tell you; but I said to George that you wouldn’t be much interested in so paltry an affair, and that it was far more likely you would rather detach yourself from us altogether, than have him added to the rest of us.’

‘That was a mistake, dear Lavvy,’ said Bella.

‘It turns out to be,’ replied Miss Lavinia; ‘but circumstances have changed, you know, my dear. George is in a new situation, and his prospects are very good indeed. I shouldn’t have had the courage to tell you so yesterday, when you would have thought his prospects poor, and not worth notice; but I feel quite bold tonight.’

‘When did you begin to feel timid, Lavvy?’ inquired Bella, with a smile.

‘I didn’t say that I ever felt timid, Bella,’ replied the Irrepressible. ‘But perhaps I might have said, if I had not been restrained by delicacy towards a sister’s feelings, that I have for some time felt independent; too independent, my dear, to subject myself to have my intended match (you’ll prick yourself again, George) looked down upon. It is not that I could have blamed you for looking down upon it, when you were looking up to a rich and great match, Bella; it is only that I was independent.’

Whether the Irrepressible felt slighted by Bella’s declaration that she would not quarrel, or whether her spitefulness was evoked by Bella’s return to the sphere of Mr George Sampson’s courtship, or whether it was a necessary fillip to her spirits that she should come into collision with somebody on the present occasion,—anyhow she made a dash at her stately parent now, with the greatest impetuosity.

‘Ma, pray don’t sit staring at me in that intensely aggravating manner! If you see a black on my nose, tell me so; if you don’t, leave me alone.’

‘Do you address Me in those words?’ said Mrs Wilfer. ‘Do you presume?’

‘Don’t talk about presuming, Ma, for goodness’ sake. A girl who is old enough to be engaged, is quite old enough to object to be stared at as if she was a Clock.’

‘Audacious one!’ said Mrs Wilfer. ‘Your grandmamma, if so addressed by one of her daughters, at any age, would have insisted on her retiring to a dark apartment.’

‘My grandmamma,’ returned Lavvy, folding her arms and leaning back in her chair, ‘wouldn’t have sat staring people out of countenance, I think.’

‘She would!’ said Mrs Wilfer.

‘Then it’s a pity she didn’t know better,’ said Lavvy. ‘And if my grandmamma wasn’t in her dotage when she took to insisting on people’s retiring to dark apartments, she ought to have been. A pretty exhibition my grandmamma must have made of herself! I wonder whether she ever insisted on people’s retiring into the ball of St Paul’s; and if she did, how she got them there!’

‘Silence!’ proclaimed Mrs Wilfer. ‘I command silence!’

‘I have not the slightest intention of being silent, Ma,’ returned Lavinia coolly, ‘but quite the contrary. I am not going to be eyed as if I had come from the Boffins, and sit silent under it. I am not going to have George Sampson eyed as if he had come from the Boffins, and sit silent under it. If Pa thinks proper to be eyed as if he had come from the Boffins also, well and good. I don’t choose to. And I won’t!’

Lavinia’s engineering having made this crooked opening at Bella, Mrs Wilfer strode into it.

‘You rebellious spirit! You mutinous child! Tell me this, Lavinia. If in violation of your mother’s sentiments, you had condescended to allow yourself to be patronized by the Boffins, and if you had come from those halls of slavery—’

‘That’s mere nonsense, Ma,’ said Lavinia.

‘How!’ exclaimed Mrs Wilfer, with sublime severity.

‘Halls of slavery, Ma, is mere stuff and nonsense,’ returned the unmoved Irrepressible.

‘I say, presumptuous child, if you had come from the neighbourhood of Portland Place, bending under the yoke of patronage and attended by its domestics in glittering garb to visit me, do you think my deep-seated feelings could have been expressed in looks?’

‘All I think about it, is,’ returned Lavinia, ‘that I should wish them expressed to the right person.’

‘And if,’ pursued her mother, ‘if making light of my warnings that the face of Mrs Boffin alone was a face teeming with evil, you had clung to Mrs Boffin instead of to me, and had after all come home rejected by Mrs Boffin, trampled under foot by Mrs Boffin, and cast out by Mrs Boffin, do you think my feelings could have been expressed in looks?’

Lavinia was about replying to her honoured parent that she might as well have dispensed with her looks altogether then, when Bella rose and said, ‘Good night, dear Ma. I have had a tiring day, and I’ll go to bed.’ This broke up the agreeable party. Mr George Sampson shortly afterwards took his leave, accompanied by Miss Lavinia with a candle as far as the hall, and without a candle as far as the garden gate; Mrs Wilfer, washing her hands of the Boffins, went to bed after the manner of Lady Macbeth; and R. W. was left alone among the dilapidations of the supper table, in a melancholy attitude.

But, a light footstep roused him from his meditations, and it was Bella’s. Her pretty hair was hanging all about her, and she had tripped down softly, brush in hand, and barefoot, to say good-night to him.

‘My dear, you most unquestionably are a lovely woman,’ said the cherub, taking up a tress in his hand.

‘Look here, sir,’ said Bella; ‘when your lovely woman marries, you shall have that piece if you like, and she’ll make you a chain of it. Would you prize that remembrance of the dear creature?’

‘Yes, my precious.’

‘Then you shall have it if you’re good, sir. I am very, very sorry, dearest Pa, to have brought home all this trouble.’

‘My pet,’ returned her father, in the simplest good faith, ‘don’t make yourself uneasy about that. It really is not worth mentioning, because things at home would have taken pretty much the same turn any way. If your mother and sister don’t find one subject to get at times a little wearing on, they find another. We’re never out of a wearing subject, my dear, I assure you. I am afraid you find your old room with Lavvy, dreadfully inconvenient, Bella?’

‘No I don’t, Pa; I don’t mind. Why don’t I mind, do you think, Pa?’

‘Well, my child, you used to complain of it when it wasn’t such a contrast as it must be now. Upon my word, I can only answer, because you are so much improved.’

‘No, Pa. Because I am so thankful and so happy!’

Here she choked him until her long hair made him sneeze, and then she laughed until she made him laugh, and then she choked him again that they might not be overheard.

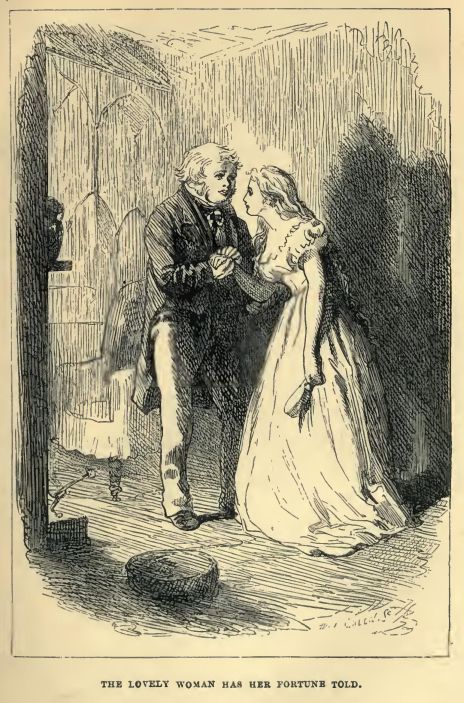

‘Listen, sir,’ said Bella. ‘Your lovely woman was told her fortune to night on her way home. It won’t be a large fortune, because if the lovely woman’s Intended gets a certain appointment that he hopes to get soon, she will marry on a hundred and fifty pounds a year. But that’s at first, and even if it should never be more, the lovely woman will make it quite enough. But that’s not all, sir. In the fortune there’s a certain fair man—a little man, the fortune-teller said—who, it seems, will always find himself near the lovely woman, and will always have kept, expressly for him, such a peaceful corner in the lovely woman’s little house as never was. Tell me the name of that man, sir.’

‘Is he a Knave in the pack of cards?’ inquired the cherub, with a twinkle in his eyes.

‘Yes!’ cried Bella, in high glee, choking him again. ‘He’s the Knave of Wilfers! Dear Pa, the lovely woman means to look forward to this fortune that has been told for her, so delightfully, and to cause it to make her a much better lovely woman than she ever has been yet. What the little fair man is expected to do, sir, is to look forward to it also, by saying to himself when he is in danger of being over-worried, “I see land at last!”

‘I see land at last!’ repeated her father.

‘There’s a dear Knave of Wilfers!’ exclaimed Bella; then putting out her small white bare foot, ‘That’s the mark, sir. Come to the mark. Put your boot against it. We keep to it together, mind! Now, sir, you may kiss the lovely woman before she runs away, so thankful and so happy. O yes, fair little man, so thankful and so happy!’