‘Cab!’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘Here you are, sir,’ shouted a strange specimen of the human race, in a sackcloth coat, and apron of the same, who, with a brass label and number round his neck, looked as if he were catalogued in some collection of rarities. This was the waterman. ‘Here you are, sir. Now, then, fust cab!’ And the first cab having been fetched from the public-house, where he had been smoking his first pipe, Mr. Pickwick and his portmanteau were thrown into the vehicle.

‘Golden Cross,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘Only a bob’s vorth, Tommy,’ cried the driver sulkily, for the information of his friend the waterman, as the cab drove off.

‘How old is that horse, my friend?’ inquired Mr. Pickwick, rubbing his nose with the shilling he had reserved for the fare.

‘Forty-two,’ replied the driver, eyeing him askant.

‘What!’ ejaculated Mr. Pickwick, laying his hand upon his note-book. The driver reiterated his former statement. Mr. Pickwick looked very hard at the man’s face, but his features were immovable, so he noted down the fact forthwith.

‘And how long do you keep him out at a time?’ inquired Mr. Pickwick, searching for further information.

‘Two or three veeks,’ replied the man.

‘Weeks!’ said Mr. Pickwick in astonishment, and out came the note-book again.

‘He lives at Pentonwil when he’s at home,’ observed the driver coolly, ‘but we seldom takes him home, on account of his weakness.’

‘On account of his weakness!’ reiterated the perplexed Mr. Pickwick.

‘He always falls down when he’s took out o’ the cab,’ continued the driver, ‘but when he’s in it, we bears him up werry tight, and takes him in werry short, so as he can’t werry well fall down; and we’ve got a pair o’ precious large wheels on, so ven he does move, they run after him, and he must go on—he can’t help it.’

Mr. Pickwick entered every word of this statement in his note-book, with the view of communicating it to the club, as a singular instance of the tenacity of life in horses under trying circumstances. The entry was scarcely completed when they reached the Golden Cross. Down jumped the driver, and out got Mr. Pickwick. Mr. Tupman, Mr. Snodgrass, and Mr. Winkle, who had been anxiously waiting the arrival of their illustrious leader, crowded to welcome him.

‘Here’s your fare,’ said Mr. Pickwick, holding out the shilling to the driver.

What was the learned man’s astonishment, when that unaccountable person flung the money on the pavement, and requested in figurative terms to be allowed the pleasure of fighting him (Mr. Pickwick) for the amount!

‘You are mad,’ said Mr. Snodgrass.

‘Or drunk,’ said Mr. Winkle.

‘Or both,’ said Mr. Tupman.

‘Come on!’ said the cab-driver, sparring away like clockwork. ‘Come on—all four on you.’

‘Here’s a lark!’ shouted half a dozen hackney coachmen. ‘Go to vork, Sam!—and they crowded with great glee round the party.

‘What’s the row, Sam?’ inquired one gentleman in black calico sleeves.

‘Row!’ replied the cabman, ‘what did he want my number for?’

‘I didn’t want your number,’ said the astonished Mr. Pickwick.

‘What did you take it for, then?’ inquired the cabman.

‘I didn’t take it,’ said Mr. Pickwick indignantly.

‘Would anybody believe,’ continued the cab-driver, appealing to the crowd, ‘would anybody believe as an informer’ud go about in a man’s cab, not only takin’ down his number, but ev’ry word he says into the bargain’ (a light flashed upon Mr. Pickwick—it was the note-book).

‘Did he though?’ inquired another cabman.

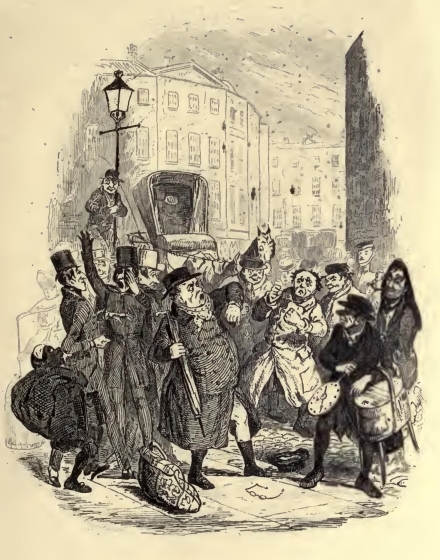

‘Yes, did he,’ replied the first; ‘and then arter aggerawatin’ me to assault him, gets three witnesses here to prove it. But I’ll give it him, if I’ve six months for it. Come on!’ and the cabman dashed his hat upon the ground, with a reckless disregard of his own private property, and knocked Mr. Pickwick’s spectacles off, and followed up the attack with a blow on Mr. Pickwick’s nose, and another on Mr. Pickwick’s chest, and a third in Mr. Snodgrass’s eye, and a fourth, by way of variety, in Mr. Tupman’s waistcoat, and then danced into the road, and then back again to the pavement, and finally dashed the whole temporary supply of breath out of Mr. Winkle’s body; and all in half a dozen seconds.

‘Where’s an officer?’ said Mr. Snodgrass.

‘Put ‘em under the pump,’ suggested a hot-pieman.

‘You shall smart for this,’ gasped Mr. Pickwick.

‘Informers!’ shouted the crowd.

‘Come on,’ cried the cabman, who had been sparring without cessation the whole time.

The mob hitherto had been passive spectators of the scene, but as the intelligence of the Pickwickians being informers was spread among them, they began to canvass with considerable vivacity the propriety of enforcing the heated pastry-vendor’s proposition: and there is no saying what acts of personal aggression they might have committed, had not the affray been unexpectedly terminated by the interposition of a new-comer.

‘What’s the fun?’ said a rather tall, thin, young man, in a green coat, emerging suddenly from the coach-yard.

‘Informers!’ shouted the crowd again.

‘We are not,’ roared Mr. Pickwick, in a tone which, to any dispassionate listener, carried conviction with it.

‘Ain’t you, though—ain’t you?’ said the young man, appealing to Mr. Pickwick, and making his way through the crowd by the infallible process of elbowing the countenances of its component members.

That learned man in a few hurried words explained the real state of the case.

‘Come along, then,’ said he of the green coat, lugging Mr. Pickwick after him by main force, and talking the whole way. Here, No. 924, take your fare, and take yourself off—respectable gentleman—know him well—none of your nonsense—this way, sir—where’s your friends?—all a mistake, I see—never mind—accidents will happen—best regulated families—never say die—down upon your luck—Pull him up—Put that in his pipe—like the flavour—damned rascals.’ And with a lengthened string of similar broken sentences, delivered with extraordinary volubility, the stranger led the way to the traveller’s waiting-room, whither he was closely followed by Mr. Pickwick and his disciples.

‘Here, waiter!’ shouted the stranger, ringing the bell with tremendous violence, ‘glasses round—brandy-and-water, hot and strong, and sweet, and plenty,—eye damaged, Sir? Waiter! raw beef-steak for the gentleman’s eye—nothing like raw beef-steak for a bruise, sir; cold lamp-post very good, but lamp-post inconvenient—damned odd standing in the open street half an hour, with your eye against a lamp-post—eh,—very good—ha! ha!’ And the stranger, without stopping to take breath, swallowed at a draught full half a pint of the reeking brandy-and-water, and flung himself into a chair with as much ease as if nothing uncommon had occurred.

While his three companions were busily engaged in proffering their thanks to their new acquaintance, Mr. Pickwick had leisure to examine his costume and appearance.

He was about the middle height, but the thinness of his body, and the length of his legs, gave him the appearance of being much taller. The green coat had been a smart dress garment in the days of swallow-tails, but had evidently in those times adorned a much shorter man than the stranger, for the soiled and faded sleeves scarcely reached to his wrists. It was buttoned closely up to his chin, at the imminent hazard of splitting the back; and an old stock, without a vestige of shirt collar, ornamented his neck. His scanty black trousers displayed here and there those shiny patches which bespeak long service, and were strapped very tightly over a pair of patched and mended shoes, as if to conceal the dirty white stockings, which were nevertheless distinctly visible. His long, black hair escaped in negligent waves from beneath each side of his old pinched-up hat; and glimpses of his bare wrists might be observed between the tops of his gloves and the cuffs of his coat sleeves. His face was thin and haggard; but an indescribable air of jaunty impudence and perfect self-possession pervaded the whole man.

Such was the individual on whom Mr. Pickwick gazed through his spectacles (which he had fortunately recovered), and to whom he proceeded, when his friends had exhausted themselves, to return in chosen terms his warmest thanks for his recent assistance.

‘Never mind,’ said the stranger, cutting the address very short, ‘said enough—no more; smart chap that cabman—handled his fives well; but if I’d been your friend in the green jemmy—damn me—punch his head,—‘cod I would,—pig’s whisper—pieman too,—no gammon.’

This coherent speech was interrupted by the entrance of the Rochester coachman, to announce that ‘the Commodore’ was on the point of starting.

‘Commodore!’ said the stranger, starting up, ‘my coach—place booked,—one outside—leave you to pay for the brandy-and-water,—want change for a five,—bad silver—Brummagem buttons—won’t do—no go—eh?’ and he shook his head most knowingly.

Now it so happened that Mr. Pickwick and his three companions had resolved to make Rochester their first halting-place too; and having intimated to their new-found acquaintance that they were journeying to the same city, they agreed to occupy the seat at the back of the coach, where they could all sit together.

‘Up with you,’ said the stranger, assisting Mr. Pickwick on to the roof with so much precipitation as to impair the gravity of that gentleman’s deportment very materially.

‘Any luggage, Sir?’ inquired the coachman.

‘Who—I? Brown paper parcel here, that’s all—other luggage gone by water—packing-cases, nailed up—big as houses—heavy, heavy, damned heavy,’ replied the stranger, as he forced into his pocket as much as he could of the brown paper parcel, which presented most suspicious indications of containing one shirt and a handkerchief.

‘Heads, heads—take care of your heads!’ cried the loquacious stranger, as they came out under the low archway, which in those days formed the entrance to the coach-yard. ‘Terrible place—dangerous work—other day—five children—mother—tall lady, eating sandwiches—forgot the arch—crash—knock—children look round—mother’s head off—sandwich in her hand—no mouth to put it in—head of a family off—shocking, shocking! Looking at Whitehall, sir?—fine place—little window—somebody else’s head off there, eh, sir?—he didn’t keep a sharp look-out enough either—eh, Sir, eh?’

‘I am ruminating,’ said Mr. Pickwick, ‘on the strange mutability of human affairs.’

‘Ah! I see—in at the palace door one day, out at the window the next. Philosopher, Sir?’

‘An observer of human nature, Sir,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘Ah, so am I. Most people are when they’ve little to do and less to get. Poet, Sir?’

‘My friend Mr. Snodgrass has a strong poetic turn,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘So have I,’ said the stranger. ‘Epic poem—ten thousand lines—revolution of July—composed it on the spot—Mars by day, Apollo by night—bang the field-piece, twang the lyre.’

‘You were present at that glorious scene, sir?’ said Mr. Snodgrass.

‘Present! think I was;* fired a musket—fired with an idea—rushed into wine shop—wrote it down—back again—whiz, bang—another idea—wine shop again—pen and ink—back again—cut and slash—noble time, Sir. Sportsman, sir?’ abruptly turning to Mr. Winkle.