‘Whom none of us believe, my dear Mrs. Bounderby, and who do not believe themselves. The only difference between us and the professors of virtue or benevolence, or philanthropy—never mind the name—is, that we know it is all meaningless, and say so; while they know it equally and will never say so.’

Why should she be shocked or warned by this reiteration? It was not so unlike her father’s principles, and her early training, that it need startle her. Where was the great difference between the two schools, when each chained her down to material realities, and inspired her with no faith in anything else? What was there in her soul for James Harthouse to destroy, which Thomas Gradgrind had nurtured there in its state of innocence!

It was even the worse for her at this pass, that in her mind—implanted there before her eminently practical father began to form it—a struggling disposition to believe in a wider and nobler humanity than she had ever heard of, constantly strove with doubts and resentments. With doubts, because the aspiration had been so laid waste in her youth. With resentments, because of the wrong that had been done her, if it were indeed a whisper of the truth. Upon a nature long accustomed to self-suppression, thus torn and divided, the Harthouse philosophy came as a relief and justification. Everything being hollow and worthless, she had missed nothing and sacrificed nothing. What did it matter, she had said to her father, when he proposed her husband. What did it matter, she said still. With a scornful self-reliance, she asked herself, What did anything matter—and went on.

Towards what? Step by step, onward and downward, towards some end, yet so gradually, that she believed herself to remain motionless. As to Mr. Harthouse, whither he tended, he neither considered nor cared. He had no particular design or plan before him: no energetic wickedness ruffled his lassitude. He was as much amused and interested, at present, as it became so fine a gentleman to be; perhaps even more than it would have been consistent with his reputation to confess. Soon after his arrival he languidly wrote to his brother, the honourable and jocular member, that the Bounderbys were ‘great fun;’ and further, that the female Bounderby, instead of being the Gorgon he had expected, was young, and remarkably pretty. After that, he wrote no more about them, and devoted his leisure chiefly to their house. He was very often in their house, in his flittings and visitings about the Coketown district; and was much encouraged by Mr. Bounderby. It was quite in Mr. Bounderby’s gusty way to boast to all his world that he didn’t care about your highly connected people, but that if his wife Tom Gradgrind’s daughter did, she was welcome to their company.

Mr. James Harthouse began to think it would be a new sensation, if the face which changed so beautifully for the whelp, would change for him.

He was quick enough to observe; he had a good memory, and did not forget a word of the brother’s revelations. He interwove them with everything he saw of the sister, and he began to understand her. To be sure, the better and profounder part of her character was not within his scope of perception; for in natures, as in seas, depth answers unto depth; but he soon began to read the rest with a student’s eye.

Mr. Bounderby had taken possession of a house and grounds, about fifteen miles from the town, and accessible within a mile or two, by a railway striding on many arches over a wild country, undermined by deserted coal-shafts, and spotted at night by fires and black shapes of stationary engines at pits’ mouths. This country, gradually softening towards the neighbourhood of Mr. Bounderby’s retreat, there mellowed into a rustic landscape, golden with heath, and snowy with hawthorn in the spring of the year, and tremulous with leaves and their shadows all the summer time. The bank had foreclosed a mortgage effected on the property thus pleasantly situated, by one of the Coketown magnates, who, in his determination to make a shorter cut than usual to an enormous fortune, overspeculated himself by about two hundred thousand pounds. These accidents did sometimes happen in the best regulated families of Coketown, but the bankrupts had no connexion whatever with the improvident classes.

It afforded Mr. Bounderby supreme satisfaction to instal himself in this snug little estate, and with demonstrative humility to grow cabbages in the flower-garden. He delighted to live, barrack-fashion, among the elegant furniture, and he bullied the very pictures with his origin. ‘Why, sir,’ he would say to a visitor, ‘I am told that Nickits,’ the late owner, ‘gave seven hundred pound for that Seabeach. Now, to be plain with you, if I ever, in the whole course of my life, take seven looks at it, at a hundred pound a look, it will be as much as I shall do. No, by George! I don’t forget that I am Josiah Bounderby of Coketown. For years upon years, the only pictures in my possession, or that I could have got into my possession, by any means, unless I stole ’em, were the engravings of a man shaving himself in a boot, on the blacking bottles that I was overjoyed to use in cleaning boots with, and that I sold when they were empty for a farthing a-piece, and glad to get it!’

Then he would address Mr. Harthouse in the same style.

‘Harthouse, you have a couple of horses down here. Bring half a dozen more if you like, and we’ll find room for ’em. There’s stabling in this place for a dozen horses; and unless Nickits is belied, he kept the full number. A round dozen of ’em, sir. When that man was a boy, he went to Westminster School. Went to Westminster School as a King’s Scholar, when I was principally living on garbage, and sleeping in market baskets. Why, if I wanted to keep a dozen horses—which I don’t, for one’s enough for me—I couldn’t bear to see ’em in their stalls here, and think what my own lodging used to be. I couldn’t look at ’em, sir, and not order ’em out. Yet so things come round. You see this place; you know what sort of a place it is; you are aware that there’s not a completer place of its size in this kingdom or elsewhere—I don’t care where—and here, got into the middle of it, like a maggot into a nut, is Josiah Bounderby. While Nickits (as a man came into my office, and told me yesterday), Nickits, who used to act in Latin, in the Westminster School plays, with the chief-justices and nobility of this country applauding him till they were black in the face, is drivelling at this minute—drivelling, sir!—in a fifth floor, up a narrow dark back street in Antwerp.’

It was among the leafy shadows of this retirement, in the long sultry summer days, that Mr. Harthouse began to prove the face which had set him wondering when he first saw it, and to try if it would change for him.

‘Mrs. Bounderby, I esteem it a most fortunate accident that I find you alone here. I have for some time had a particular wish to speak to you.’

It was not by any wonderful accident that he found her, the time of day being that at which she was always alone, and the place being her favourite resort. It was an opening in a dark wood, where some felled trees lay, and where she would sit watching the fallen leaves of last year, as she had watched the falling ashes at home.

He sat down beside her, with a glance at her face.

‘Your brother. My young friend Tom—’

Her colour brightened, and she turned to him with a look of interest. ‘I never in my life,’ he thought, ‘saw anything so remarkable and so captivating as the lighting of those features!’ His face betrayed his thoughts—perhaps without betraying him, for it might have been according to its instructions so to do.

‘Pardon me. The expression of your sisterly interest is so beautiful—Tom should be so proud of it—I know this is inexcusable, but I am so compelled to admire.’

‘Being so impulsive,’ she said composedly.

‘Mrs. Bounderby, no: you know I make no pretence with you. You know I am a sordid piece of human nature, ready to sell myself at any time for any reasonable sum, and altogether incapable of any Arcadian proceeding whatever.’

‘I am waiting,’ she returned, ‘for your further reference to my brother.’

‘You are rigid with me, and I deserve it. I am as worthless a dog as you will find, except that I am not false—not false. But you surprised and started me from my subject, which was your brother. I have an interest in him.’

‘Have you an interest in anything, Mr. Harthouse?’ she asked, half incredulously and half gratefully.

‘If you had asked me when I first came here, I should have said no. I must say now—even at the hazard of appearing to make a pretence, and of justly awakening your incredulity—yes.’

She made a slight movement, as if she were trying to speak, but could not find voice; at length she said, ‘Mr. Harthouse, I give you credit for being interested in my brother.’

‘Thank you. I claim to deserve it. You know how little I do claim, but I will go that length. You have done so much for him, you are so fond of him; your whole life, Mrs. Bounderby, expresses such charming self-forgetfulness on his account—pardon me again—I am running wide of the subject. I am interested in him for his own sake.’

She had made the slightest action possible, as if she would have risen in a hurry and gone away. He had turned the course of what he said at that instant, and she remained.

‘Mrs. Bounderby,’ he resumed, in a lighter manner, and yet with a show of effort in assuming it, which was even more expressive than the manner he dismissed; ‘it is no irrevocable offence in a young fellow of your brother’s years, if he is heedless, inconsiderate, and expensive—a little dissipated, in the common phrase. Is he?’

‘Yes.’

‘Allow me to be frank. Do you think he games at all?’

‘I think he makes bets.’ Mr. Harthouse waiting, as if that were not her whole answer, she added, ‘I know he does.’

‘Of course he loses?’

‘Yes.’

‘Everybody does lose who bets. May I hint at the probability of your sometimes supplying him with money for these purposes?’

She sat, looking down; but, at this question, raised her eyes searchingly and a little resentfully.

‘Acquit me of impertinent curiosity, my dear Mrs. Bounderby. I think Tom may be gradually falling into trouble, and I wish to stretch out a helping hand to him from the depths of my wicked experience.—Shall I say again, for his sake? Is that necessary?’

She seemed to try to answer, but nothing came of it.

‘Candidly to confess everything that has occurred to me,’ said James Harthouse, again gliding with the same appearance of effort into his more airy manner; ‘I will confide to you my doubt whether he has had many advantages. Whether—forgive my plainness—whether any great amount of confidence is likely to have been established between himself and his most worthy father.’

‘I do not,’ said Louisa, flushing with her own great remembrance in that wise, ‘think it likely.’

‘Or, between himself, and—I may trust to your perfect understanding of my meaning, I am sure—and his highly esteemed brother-in-law.’

She flushed deeper and deeper, and was burning red when she replied in a fainter voice, ‘I do not think that likely, either.’

‘Mrs. Bounderby,’ said Harthouse, after a short silence, ‘may there be a better confidence between yourself and me? Tom has borrowed a considerable sum of you?’

‘You will understand, Mr. Harthouse,’ she returned, after some indecision: she had been more or less uncertain, and troubled throughout the conversation, and yet had in the main preserved her self-contained manner; ‘you will understand that if I tell you what you press to know, it is not by way of complaint or regret. I would never complain of anything, and what I have done I do not in the least regret.’

‘So spirited, too!’ thought James Harthouse.

‘When I married, I found that my brother was even at that time heavily in debt. Heavily for him, I mean. Heavily enough to oblige me to sell some trinkets. They were no sacrifice. I sold them very willingly. I attached no value to them. They, were quite worthless to me.’

Either she saw in his face that he knew, or she only feared in her conscience that he knew, that she spoke of some of her husband’s gifts. She stopped, and reddened again. If he had not known it before, he would have known it then, though he had been a much duller man than he was.

‘Since then, I have given my brother, at various times, what money I could spare: in short, what money I have had. Confiding in you at all, on the faith of the interest you profess for him, I will not do so by halves. Since you have been in the habit of visiting here, he has wanted in one sum as much as a hundred pounds. I have not been able to give it to him. I have felt uneasy for the consequences of his being so involved, but I have kept these secrets until now, when I trust them to your honour. I have held no confidence with any one, because—you anticipated my reason just now.’ She abruptly broke off.

He was a ready man, and he saw, and seized, an opportunity here of presenting her own image to her, slightly disguised as her brother.

‘Mrs. Bounderby, though a graceless person, of the world worldly, I feel the utmost interest, I assure you, in what you tell me. I cannot possibly be hard upon your brother. I understand and share the wise consideration with which you regard his errors. With all possible respect both for Mr. Gradgrind and for Mr. Bounderby, I think I perceive that he has not been fortunate in his training. Bred at a disadvantage towards the society in which he has his part to play, he rushes into these extremes for himself, from opposite extremes that have long been forced—with the very best intentions we have no doubt—upon him. Mr. Bounderby’s fine bluff English independence, though a most charming characteristic, does not—as we have agreed—invite confidence. If I might venture to remark that it is the least in the world deficient in that delicacy to which a youth mistaken, a character misconceived, and abilities misdirected, would turn for relief and guidance, I should express what it presents to my own view.’

As she sat looking straight before her, across the changing lights upon the grass into the darkness of the wood beyond, he saw in her face her application of his very distinctly uttered words.

‘All allowance,’ he continued, ‘must be made. I have one great fault to find with Tom, however, which I cannot forgive, and for which I take him heavily to account.’

Louisa turned her eyes to his face, and asked him what fault was that?

‘Perhaps,’ he returned, ‘I have said enough. Perhaps it would have been better, on the whole, if no allusion to it had escaped me.’

‘You alarm me, Mr. Harthouse. Pray let me know it.’

‘To relieve you from needless apprehension—and as this confidence regarding your brother, which I prize I am sure above all possible things, has been established between us—I obey. I cannot forgive him for not being more sensible in every word, look, and act of his life, of the affection of his best friend; of the devotion of his best friend; of her unselfishness; of her sacrifice. The return he makes her, within my observation, is a very poor one. What she has done for him demands his constant love and gratitude, not his ill-humour and caprice. Careless fellow as I am, I am not so indifferent, Mrs. Bounderby, as to be regardless of this vice in your brother, or inclined to consider it a venial offence.’

The wood floated before her, for her eyes were suffused with tears. They rose from a deep well, long concealed, and her heart was filled with acute pain that found no relief in them.

‘In a word, it is to correct your brother in this, Mrs. Bounderby, that I must aspire. My better knowledge of his circumstances, and my direction and advice in extricating them—rather valuable, I hope, as coming from a scapegrace on a much larger scale—will give me some influence over him, and all I gain I shall certainly use towards this end. I have said enough, and more than enough. I seem to be protesting that I am a sort of good fellow, when, upon my honour, I have not the least intention to make any protestation to that effect, and openly announce that I am nothing of the sort. Yonder, among the trees,’ he added, having lifted up his eyes and looked about; for he had watched her closely until now; ‘is your brother himself; no doubt, just come down. As he seems to be loitering in this direction, it may be as well, perhaps, to walk towards him, and throw ourselves in his way. He has been very silent and doleful of late. Perhaps, his brotherly conscience is touched—if there are such things as consciences. Though, upon my honour, I hear of them much too often to believe in them.’

He assisted her to rise, and she took his arm, and they advanced to meet the whelp. He was idly beating the branches as he lounged along: or he stooped viciously to rip the moss from the trees with his stick. He was startled when they came upon him while he was engaged in this latter pastime, and his colour changed.

‘Halloa!’ he stammered; ‘I didn’t know you were here.’

‘Whose name, Tom,’ said Mr. Harthouse, putting his hand upon his shoulder and turning him, so that they all three walked towards the house together, ‘have you been carving on the trees?’

‘Whose name?’ returned Tom. ‘Oh! You mean what girl’s name?’

‘You have a suspicious appearance of inscribing some fair creature’s on the bark, Tom.’

‘Not much of that, Mr. Harthouse, unless some fair creature with a slashing fortune at her own disposal would take a fancy to me. Or she might be as ugly as she was rich, without any fear of losing me. I’d carve her name as often as she liked.’

‘I am afraid you are mercenary, Tom.’

‘Mercenary,’ repeated Tom. ‘Who is not mercenary? Ask my sister.’

‘Have you so proved it to be a failing of mine, Tom?’ said Louisa, showing no other sense of his discontent and ill-nature.

‘You know whether the cap fits you, Loo,’ returned her brother sulkily. ‘If it does, you can wear it.’

‘Tom is misanthropical to-day, as all bored people are now and then,’ said Mr. Harthouse. ‘Don’t believe him, Mrs. Bounderby. He knows much better. I shall disclose some of his opinions of you, privately expressed to me, unless he relents a little.’

‘At all events, Mr. Harthouse,’ said Tom, softening in his admiration of his patron, but shaking his head sullenly too, ‘you can’t tell her that I ever praised her for being mercenary. I may have praised her for being the contrary, and I should do it again, if I had as good reason. However, never mind this now; it’s not very interesting to you, and I am sick of the subject.’

They walked on to the house, where Louisa quitted her visitor’s arm and went in. He stood looking after her, as she ascended the steps, and passed into the shadow of the door; then put his hand upon her brother’s shoulder again, and invited him with a confidential nod to a walk in the garden.

‘Tom, my fine fellow, I want to have a word with you.’

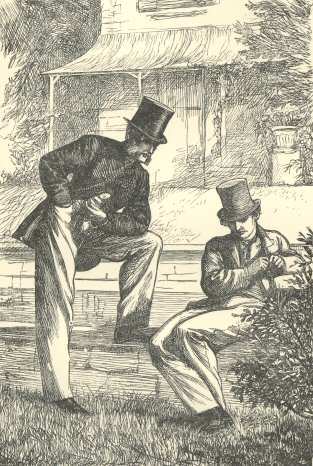

They had stopped among a disorder of roses—it was part of Mr. Bounderby’s humility to keep Nickits’s roses on a reduced scale—and Tom sat down on a terrace-parapet, plucking buds and picking them to pieces; while his powerful Familiar stood over him, with a foot upon the parapet, and his figure easily resting on the arm supported by that knee. They were just visible from her window. Perhaps she saw them.

‘Tom, what’s the matter?’

‘Oh! Mr. Harthouse,’ said Tom with a groan, ‘I am hard up, and bothered out of my life.’

‘My good fellow, so am I.’

‘You!’ returned Tom. ‘You are the picture of independence. Mr. Harthouse, I am in a horrible mess. You have no idea what a state I have got myself into—what a state my sister might have got me out of, if she would only have done it.’

He took to biting the rosebuds now, and tearing them away from his teeth with a hand that trembled like an infirm old man’s. After one exceedingly observant look at him, his companion relapsed into his lightest air.

‘Tom, you are inconsiderate: you expect too much of your sister. You have had money of her, you dog, you know you have.’

‘Well, Mr. Harthouse, I know I have. How else was I to get it? Here’s old Bounderby always boasting that at my age he lived upon twopence a month, or something of that sort. Here’s my father drawing what he calls a line, and tying me down to it from a baby, neck and heels. Here’s my mother who never has anything of her own, except her complaints. What is a fellow to do for money, and where am I to look for it, if not to my sister?’

He was almost crying, and scattered the buds about by dozens. Mr. Harthouse took him persuasively by the coat.

‘But, my dear Tom, if your sister has not got it—’

‘Not got it, Mr. Harthouse? I don’t say she has got it. I may have wanted more than she was likely to have got. But then she ought to get it. She could get it. It’s of no use pretending to make a secret of matters now, after what I have told you already; you know she didn’t marry old Bounderby for her own sake, or for his sake, but for my sake. Then why doesn’t she get what I want, out of him, for my sake? She is not obliged to say what she is going to do with it; she is sharp enough; she could manage to coax it out of him, if she chose. Then why doesn’t she choose, when I tell her of what consequence it is? But no. There she sits in his company like a stone, instead of making herself agreeable and getting it easily. I don’t know what you may call this, but I call it unnatural conduct.’

There was a piece of ornamental water immediately below the parapet, on the other side, into which Mr. James Harthouse had a very strong inclination to pitch Mr. Thomas Gradgrind junior, as the injured men of Coketown threatened to pitch their property into the Atlantic. But he preserved his easy attitude; and nothing more solid went over the stone balustrades than the accumulated rosebuds now floating about, a little surface-island.

‘My dear Tom,’ said Harthouse, ‘let me try to be your banker.’

‘For God’s sake,’ replied Tom, suddenly, ‘don’t talk about bankers!’ And very white he looked, in contrast with the roses. Very white.

Mr. Harthouse, as a thoroughly well-bred man, accustomed to the best society, was not to be surprised—he could as soon have been affected—but he raised his eyelids a little more, as if they were lifted by a feeble touch of wonder. Albeit it was as much against the precepts of his school to wonder, as it was against the doctrines of the Gradgrind College.

‘What is the present need, Tom? Three figures? Out with them. Say what they are.’

‘Mr. Harthouse,’ returned Tom, now actually crying; and his tears were better than his injuries, however pitiful a figure he made: ‘it’s too late; the money is of no use to me at present. I should have had it before to be of use to me. But I am very much obliged to you; you’re a true friend.’

A true friend! ‘Whelp, whelp!’ thought Mr. Harthouse, lazily; ‘what an Ass you are!’

‘And I take your offer as a great kindness,’ said Tom, grasping his hand. ‘As a great kindness, Mr. Harthouse.’

‘Well,’ returned the other, ‘it may be of more use by and by. And, my good fellow, if you will open your bedevilments to me when they come thick upon you, I may show you better ways out of them than you can find for yourself.’

‘Thank you,’ said Tom, shaking his head dismally, and chewing rosebuds. ‘I wish I had known you sooner, Mr. Harthouse.’

‘Now, you see, Tom,’ said Mr. Harthouse in conclusion, himself tossing over a rose or two, as a contribution to the island, which was always drifting to the wall as if it wanted to become a part of the mainland: ‘every man is selfish in everything he does, and I am exactly like the rest of my fellow-creatures. I am desperately intent;’ the languor of his desperation being quite tropical; ‘on your softening towards your sister—which you ought to do; and on your being a more loving and agreeable sort of brother—which you ought to be.’

‘I will be, Mr. Harthouse.’

‘No time like the present, Tom. Begin at once.’

‘Certainly I will. And my sister Loo shall say so.’

‘Having made which bargain, Tom,’ said Harthouse, clapping him on the shoulder again, with an air which left him at liberty to infer—as he did, poor fool—that this condition was imposed upon him in mere careless good nature to lessen his sense of obligation, ‘we will tear ourselves asunder until dinner-time.’

When Tom appeared before dinner, though his mind seemed heavy enough, his body was on the alert; and he appeared before Mr. Bounderby came in. ‘I didn’t mean to be cross, Loo,’ he said, giving her his hand, and kissing her. ‘I know you are fond of me, and you know I am fond of you.’

After this, there was a smile upon Louisa’s face that day, for some one else. Alas, for some one else!

‘So much the less is the whelp the only creature that she cares for,’ thought James Harthouse, reversing the reflection of his first day’s knowledge of her pretty face. ‘So much the less, so much the less.’