A very few French leagues of his journey were accomplished, when Charles Darnay began to perceive that for him along these country roads there was no hope of return until he should have been declared a good citizen at Paris. Whatever might befall now, he must on to his journey’s end. Not a mean village closed upon him, not a common barrier dropped across the road behind him, but he knew it to be another iron door in the series that was barred between him and England. The universal watchfulness so encompassed him, that if he had been taken in a net, or were being forwarded to his destination in a cage, he could not have felt his freedom more completely gone.

This universal watchfulness not only stopped him on the highway twenty times in a stage, but retarded his progress twenty times in a day, by riding after him and taking him back, riding before him and stopping him by anticipation, riding with him and keeping him in charge. He had been days upon his journey in France alone, when he went to bed tired out, in a little town on the high road, still a long way from Paris.

Nothing but the production of the afflicted Gabelle’s letter from his prison of the Abbaye would have got him on so far. His difficulty at the guard-house in this small place had been such, that he felt his journey to have come to a crisis. And he was, therefore, as little surprised as a man could be, to find himself awakened at the small inn to which he had been remitted until morning, in the middle of the night.

Awakened by a timid local functionary and three armed patriots in rough red caps and with pipes in their mouths, who sat down on the bed.

“Emigrant,” said the functionary, “I am going to send you on to Paris, under an escort.”

“Citizen, I desire nothing more than to get to Paris, though I could dispense with the escort.”

“Silence!” growled a red-cap, striking at the coverlet with the butt-end of his musket. “Peace, aristocrat!”

“It is as the good patriot says,” observed the timid functionary. “You are an aristocrat, and must have an escort—and must pay for it.”

“I have no choice,” said Charles Darnay.

“Choice! Listen to him!” cried the same scowling red-cap. “As if it was not a favour to be protected from the lamp-iron!”

“It is always as the good patriot says,” observed the functionary. “Rise and dress yourself, emigrant.”

Darnay complied, and was taken back to the guard-house, where other patriots in rough red caps were smoking, drinking, and sleeping, by a watch-fire. Here he paid a heavy price for his escort, and hence he started with it on the wet, wet roads at three o’clock in the morning.

The escort were two mounted patriots in red caps and tri-coloured cockades, armed with national muskets and sabres, who rode one on either side of him.

The escorted governed his own horse, but a loose line was attached to his bridle, the end of which one of the patriots kept girded round his wrist. In this state they set forth with the sharp rain driving in their faces: clattering at a heavy dragoon trot over the uneven town pavement, and out upon the mire-deep roads. In this state they traversed without change, except of horses and pace, all the mire-deep leagues that lay between them and the capital.

They travelled in the night, halting an hour or two after daybreak, and lying by until the twilight fell. The escort were so wretchedly clothed, that they twisted straw round their bare legs, and thatched their ragged shoulders to keep the wet off. Apart from the personal discomfort of being so attended, and apart from such considerations of present danger as arose from one of the patriots being chronically drunk, and carrying his musket very recklessly, Charles Darnay did not allow the restraint that was laid upon him to awaken any serious fears in his breast; for, he reasoned with himself that it could have no reference to the merits of an individual case that was not yet stated, and of representations, confirmable by the prisoner in the Abbaye, that were not yet made.

But when they came to the town of Beauvais—which they did at eventide, when the streets were filled with people—he could not conceal from himself that the aspect of affairs was very alarming. An ominous crowd gathered to see him dismount of the posting-yard, and many voices called out loudly, “Down with the emigrant!”

He stopped in the act of swinging himself out of his saddle, and, resuming it as his safest place, said:

“Emigrant, my friends! Do you not see me here, in France, of my own will?”

“You are a cursed emigrant,” cried a farrier, making at him in a furious manner through the press, hammer in hand; “and you are a cursed aristocrat!”

The postmaster interposed himself between this man and the rider’s bridle (at which he was evidently making), and soothingly said, “Let him be; let him be! He will be judged at Paris.”

“Judged!” repeated the farrier, swinging his hammer. “Ay! and condemned as a traitor.” At this the crowd roared approval.

Checking the postmaster, who was for turning his horse’s head to the yard (the drunken patriot sat composedly in his saddle looking on, with the line round his wrist), Darnay said, as soon as he could make his voice heard:

“Friends, you deceive yourselves, or you are deceived. I am not a traitor.”

“He lies!” cried the smith. “He is a traitor since the decree. His life is forfeit to the people. His cursed life is not his own!”

At the instant when Darnay saw a rush in the eyes of the crowd, which another instant would have brought upon him, the postmaster turned his horse into the yard, the escort rode in close upon his horse’s flanks, and the postmaster shut and barred the crazy double gates. The farrier struck a blow upon them with his hammer, and the crowd groaned; but, no more was done.

“What is this decree that the smith spoke of?” Darnay asked the postmaster, when he had thanked him, and stood beside him in the yard.

“Truly, a decree for selling the property of emigrants.”

“When passed?”

“On the fourteenth.”

“The day I left England!”

“Everybody says it is but one of several, and that there will be others—if there are not already—banishing all emigrants, and condemning all to death who return. That is what he meant when he said your life was not your own.”

“But there are no such decrees yet?”

“What do I know!” said the postmaster, shrugging his shoulders; “there may be, or there will be. It is all the same. What would you have?”

They rested on some straw in a loft until the middle of the night, and then rode forward again when all the town was asleep. Among the many wild changes observable on familiar things which made this wild ride unreal, not the least was the seeming rarity of sleep. After long and lonely spurring over dreary roads, they would come to a cluster of poor cottages, not steeped in darkness, but all glittering with lights, and would find the people, in a ghostly manner in the dead of the night, circling hand in hand round a shrivelled tree of Liberty, or all drawn up together singing a Liberty song. Happily, however, there was sleep in Beauvais that night to help them out of it and they passed on once more into solitude and loneliness: jingling through the untimely cold and wet, among impoverished fields that had yielded no fruits of the earth that year, diversified by the blackened remains of burnt houses, and by the sudden emergence from ambuscade, and sharp reining up across their way, of patriot patrols on the watch on all the roads.

Daylight at last found them before the wall of Paris. The barrier was closed and strongly guarded when they rode up to it.

“Where are the papers of this prisoner?” demanded a resolute-looking man in authority, who was summoned out by the guard.

Naturally struck by the disagreeable word, Charles Darnay requested the speaker to take notice that he was a free traveller and French citizen, in charge of an escort which the disturbed state of the country had imposed upon him, and which he had paid for.

“Where,” repeated the same personage, without taking any heed of him whatever, “are the papers of this prisoner?”

The drunken patriot had them in his cap, and produced them. Casting his eyes over Gabelle’s letter, the same personage in authority showed some disorder and surprise, and looked at Darnay with a close attention.

He left escort and escorted without saying a word, however, and went into the guard-room; meanwhile, they sat upon their horses outside the gate. Looking about him while in this state of suspense, Charles Darnay observed that the gate was held by a mixed guard of soldiers and patriots, the latter far outnumbering the former; and that while ingress into the city for peasants’ carts bringing in supplies, and for similar traffic and traffickers, was easy enough, egress, even for the homeliest people, was very difficult. A numerous medley of men and women, not to mention beasts and vehicles of various sorts, was waiting to issue forth; but, the previous identification was so strict, that they filtered through the barrier very slowly. Some of these people knew their turn for examination to be so far off, that they lay down on the ground to sleep or smoke, while others talked together, or loitered about. The red cap and tri-colour cockade were universal, both among men and women.

When he had sat in his saddle some half-hour, taking note of these things, Darnay found himself confronted by the same man in authority, who directed the guard to open the barrier. Then he delivered to the escort, drunk and sober, a receipt for the escorted, and requested him to dismount. He did so, and the two patriots, leading his tired horse, turned and rode away without entering the city.

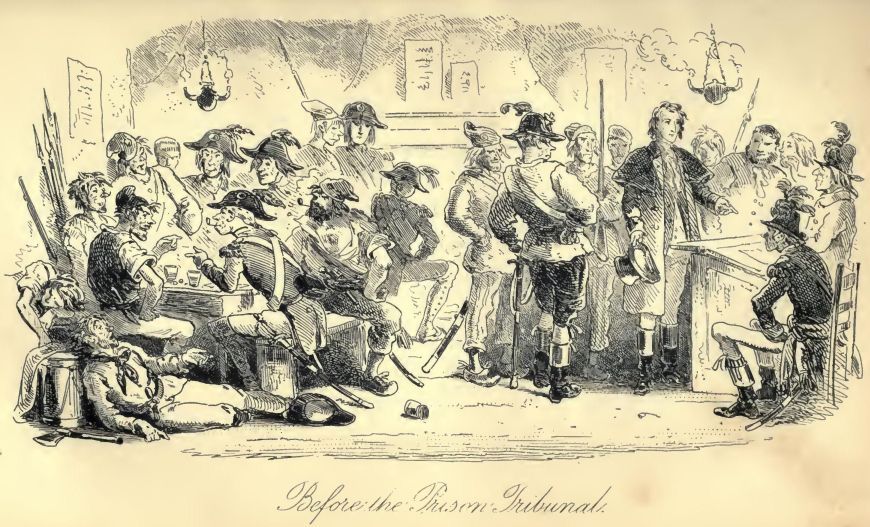

He accompanied his conductor into a guard-room, smelling of common wine and tobacco, where certain soldiers and patriots, asleep and awake, drunk and sober, and in various neutral states between sleeping and waking, drunkenness and sobriety, were standing and lying about. The light in the guard-house, half derived from the waning oil-lamps of the night, and half from the overcast day, was in a correspondingly uncertain condition. Some registers were lying open on a desk, and an officer of a coarse, dark aspect, presided over these.

“Citizen Defarge,” said he to Darnay’s conductor, as he took a slip of paper to write on. “Is this the emigrant Evrémonde?”

“This is the man.”

“Your age, Evrémonde?”

“Thirty-seven.”

“Married, Evrémonde?”

“Yes.”

“Where married?”

“In England.”

“Without doubt. Where is your wife, Evrémonde?”

“In England.”

“Without doubt. You are consigned, Evrémonde, to the prison of La Force.”

“Just Heaven!” exclaimed Darnay. “Under what law, and for what offence?”

The officer looked up from his slip of paper for a moment.

“We have new laws, Evrémonde, and new offences, since you were here.” He said it with a hard smile, and went on writing.

“I entreat you to observe that I have come here voluntarily, in response to that written appeal of a fellow-countryman which lies before you. I demand no more than the opportunity to do so without delay. Is not that my right?”

“Emigrants have no rights, Evrémonde,” was the stolid reply. The officer wrote until he had finished, read over to himself what he had written, sanded it, and handed it to Defarge, with the words “In secret.”

Defarge motioned with the paper to the prisoner that he must accompany him. The prisoner obeyed, and a guard of two armed patriots attended them.

“Is it you,” said Defarge, in a low voice, as they went down the guardhouse steps and turned into Paris, “who married the daughter of Doctor Manette, once a prisoner in the Bastille that is no more?”

“Yes,” replied Darnay, looking at him with surprise.

“My name is Defarge, and I keep a wine-shop in the Quarter Saint Antoine. Possibly you have heard of me.”

“My wife came to your house to reclaim her father? Yes!”

The word “wife” seemed to serve as a gloomy reminder to Defarge, to say with sudden impatience, “In the name of that sharp female newly-born, and called La Guillotine, why did you come to France?”

“You heard me say why, a minute ago. Do you not believe it is the truth?”

“A bad truth for you,” said Defarge, speaking with knitted brows, and looking straight before him.

“Indeed I am lost here. All here is so unprecedented, so changed, so sudden and unfair, that I am absolutely lost. Will you render me a little help?”

“None.” Defarge spoke, always looking straight before him.

“Will you answer me a single question?”

“Perhaps. According to its nature. You can say what it is.”

“In this prison that I am going to so unjustly, shall I have some free communication with the world outside?”

“You will see.”

“I am not to be buried there, prejudged, and without any means of presenting my case?”

“You will see. But, what then? Other people have been similarly buried in worse prisons, before now.”

“But never by me, Citizen Defarge.”

Defarge glanced darkly at him for answer, and walked on in a steady and set silence. The deeper he sank into this silence, the fainter hope there was—or so Darnay thought—of his softening in any slight degree. He, therefore, made haste to say:

“It is of the utmost importance to me (you know, Citizen, even better than I, of how much importance), that I should be able to communicate to Mr. Lorry of Tellson’s Bank, an English gentleman who is now in Paris, the simple fact, without comment, that I have been thrown into the prison of La Force. Will you cause that to be done for me?”

“I will do,” Defarge doggedly rejoined, “nothing for you. My duty is to my country and the People. I am the sworn servant of both, against you. I will do nothing for you.”

Charles Darnay felt it hopeless to entreat him further, and his pride was touched besides. As they walked on in silence, he could not but see how used the people were to the spectacle of prisoners passing along the streets. The very children scarcely noticed him. A few passers turned their heads, and a few shook their fingers at him as an aristocrat; otherwise, that a man in good clothes should be going to prison, was no more remarkable than that a labourer in working clothes should be going to work. In one narrow, dark, and dirty street through which they passed, an excited orator, mounted on a stool, was addressing an excited audience on the crimes against the people, of the king and the royal family. The few words that he caught from this man’s lips, first made it known to Charles Darnay that the king was in prison, and that the foreign ambassadors had one and all left Paris. On the road (except at Beauvais) he had heard absolutely nothing. The escort and the universal watchfulness had completely isolated him.

That he had fallen among far greater dangers than those which had developed themselves when he left England, he of course knew now. That perils had thickened about him fast, and might thicken faster and faster yet, he of course knew now. He could not but admit to himself that he might not have made this journey, if he could have foreseen the events of a few days. And yet his misgivings were not so dark as, imagined by the light of this later time, they would appear. Troubled as the future was, it was the unknown future, and in its obscurity there was ignorant hope. The horrible massacre, days and nights long, which, within a few rounds of the clock, was to set a great mark of blood upon the blessed garnering time of harvest, was as far out of his knowledge as if it had been a hundred thousand years away. The “sharp female newly-born, and called La Guillotine,” was hardly known to him, or to the generality of people, by name. The frightful deeds that were to be soon done, were probably unimagined at that time in the brains of the doers. How could they have a place in the shadowy conceptions of a gentle mind?

Of unjust treatment in detention and hardship, and in cruel separation from his wife and child, he foreshadowed the likelihood, or the certainty; but, beyond this, he dreaded nothing distinctly. With this on his mind, which was enough to carry into a dreary prison courtyard, he arrived at the prison of La Force.

A man with a bloated face opened the strong wicket, to whom Defarge presented “The Emigrant Evrémonde.”

“What the Devil! How many more of them!” exclaimed the man with the bloated face.

Defarge took his receipt without noticing the exclamation, and withdrew, with his two fellow-patriots.

“What the Devil, I say again!” exclaimed the gaoler, left with his wife. “How many more!”

The gaoler’s wife, being provided with no answer to the question, merely replied, “One must have patience, my dear!” Three turnkeys who entered responsive to a bell she rang, echoed the sentiment, and one added, “For the love of Liberty;” which sounded in that place like an inappropriate conclusion.

The prison of La Force was a gloomy prison, dark and filthy, and with a horrible smell of foul sleep in it. Extraordinary how soon the noisome flavour of imprisoned sleep, becomes manifest in all such places that are ill cared for!

“In secret, too,” grumbled the gaoler, looking at the written paper. “As if I was not already full to bursting!”

He stuck the paper on a file, in an ill-humour, and Charles Darnay awaited his further pleasure for half an hour: sometimes, pacing to and fro in the strong arched room: sometimes, resting on a stone seat: in either case detained to be imprinted on the memory of the chief and his subordinates.

“Come!” said the chief, at length taking up his keys, “come with me, emigrant.”

Through the dismal prison twilight, his new charge accompanied him by corridor and staircase, many doors clanging and locking behind them, until they came into a large, low, vaulted chamber, crowded with prisoners of both sexes. The women were seated at a long table, reading and writing, knitting, sewing, and embroidering; the men were for the most part standing behind their chairs, or lingering up and down the room.

In the instinctive association of prisoners with shameful crime and disgrace, the new-comer recoiled from this company. But the crowning unreality of his long unreal ride, was, their all at once rising to receive him, with every refinement of manner known to the time, and with all the engaging graces and courtesies of life.

So strangely clouded were these refinements by the prison manners and gloom, so spectral did they become in the inappropriate squalor and misery through which they were seen, that Charles Darnay seemed to stand in a company of the dead. Ghosts all! The ghost of beauty, the ghost of stateliness, the ghost of elegance, the ghost of pride, the ghost of frivolity, the ghost of wit, the ghost of youth, the ghost of age, all waiting their dismissal from the desolate shore, all turning on him eyes that were changed by the death they had died in coming there.

It struck him motionless. The gaoler standing at his side, and the other gaolers moving about, who would have been well enough as to appearance in the ordinary exercise of their functions, looked so extravagantly coarse contrasted with sorrowing mothers and blooming daughters who were there—with the apparitions of the coquette, the young beauty, and the mature woman delicately bred—that the inversion of all experience and likelihood which the scene of shadows presented, was heightened to its utmost. Surely, ghosts all. Surely, the long unreal ride some progress of disease that had brought him to these gloomy shades!

“In the name of the assembled companions in misfortune,” said a gentleman of courtly appearance and address, coming forward, “I have the honour of giving you welcome to La Force, and of condoling with you on the calamity that has brought you among us. May it soon terminate happily! It would be an impertinence elsewhere, but it is not so here, to ask your name and condition?”

Charles Darnay roused himself, and gave the required information, in words as suitable as he could find.

“But I hope,” said the gentleman, following the chief gaoler with his eyes, who moved across the room, “that you are not in secret?”

“I do not understand the meaning of the term, but I have heard them say so.”

“Ah, what a pity! We so much regret it! But take courage; several members of our society have been in secret, at first, and it has lasted but a short time.” Then he added, raising his voice, “I grieve to inform the society—in secret.”

There was a murmur of commiseration as Charles Darnay crossed the room to a grated door where the gaoler awaited him, and many voices—among which, the soft and compassionate voices of women were conspicuous—gave him good wishes and encouragement. He turned at the grated door, to render the thanks of his heart; it closed under the gaoler’s hand; and the apparitions vanished from his sight forever.

The wicket opened on a stone staircase, leading upward. When they had ascended forty steps (the prisoner of half an hour already counted them), the gaoler opened a low black door, and they passed into a solitary cell. It struck cold and damp, but was not dark.

“Yours,” said the gaoler.

“Why am I confined alone?”

“How do I know!”

“I can buy pen, ink, and paper?”

“Such are not my orders. You will be visited, and can ask then. At present, you may buy your food, and nothing more.”

There were in the cell, a chair, a table, and a straw mattress. As the gaoler made a general inspection of these objects, and of the four walls, before going out, a wandering fancy wandered through the mind of the prisoner leaning against the wall opposite to him, that this gaoler was so unwholesomely bloated, both in face and person, as to look like a man who had been drowned and filled with water. When the gaoler was gone, he thought in the same wandering way, “Now am I left, as if I were dead.” Stopping then, to look down at the mattress, he turned from it with a sick feeling, and thought, “And here in these crawling creatures is the first condition of the body after death.”

“Five paces by four and a half, five paces by four and a half, five paces by four and a half.” The prisoner walked to and fro in his cell, counting its measurement, and the roar of the city arose like muffled drums with a wild swell of voices added to them. “He made shoes, he made shoes, he made shoes.” The prisoner counted the measurement again, and paced faster, to draw his mind with him from that latter repetition. “The ghosts that vanished when the wicket closed. There was one among them, the appearance of a lady dressed in black, who was leaning in the embrasure of a window, and she had a light shining upon her golden hair, and she looked like * * * * Let us ride on again, for God’s sake, through the illuminated villages with the people all awake! * * * * He made shoes, he made shoes, he made shoes. * * * * Five paces by four and a half.” With such scraps tossing and rolling upward from the depths of his mind, the prisoner walked faster and faster, obstinately counting and counting; and the roar of the city changed to this extent—that it still rolled in like muffled drums, but with the wail of voices that he knew, in the swell that rose above them.